Domestic violence: When safer at home might be unsafe

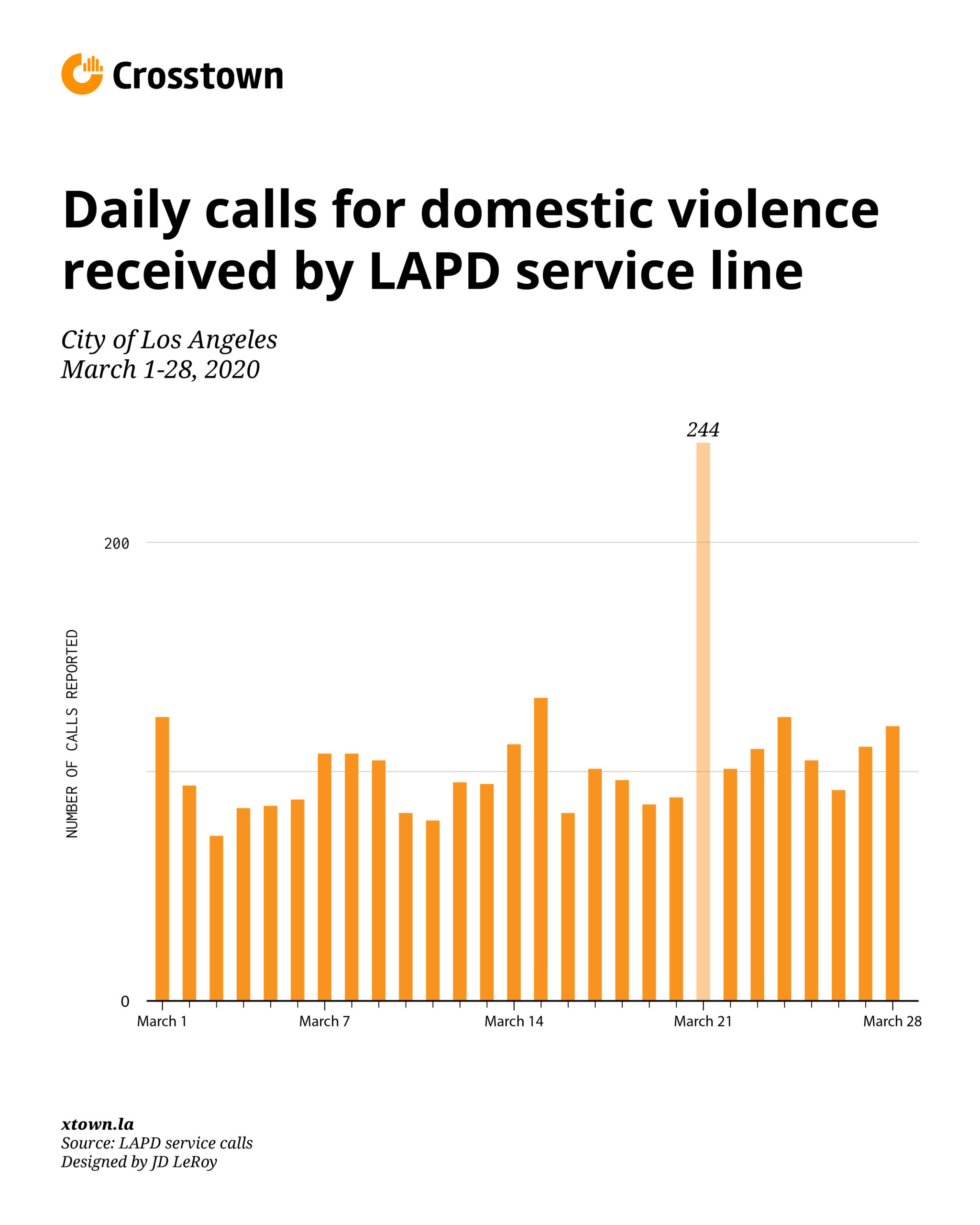

On March 21, two days after California’s Safer at Home order went into effect, the Los Angeles Police Department was deluged with calls about domestic violence.

That day, it received 244 service calls related to domestic abuse incidents, the most it has received so far this year, and a 240% jump from the daily average for the previous month, according to publicly available data. (Service calls are a record of all instances that LAPD officers respond to, including calls that come in over 911, the department’s non-emergency number and events that officers respond to in the field.)*

The sudden spike may be an early signal of one of the brutal side effects of staying at home to limit the spread of COVID-19. Victims’ advocates fear that protracted confinement could cause domestic tensions to flare, resulting in an increase in violence. It is still early to get a clear picture from the data, and experts caution that calls about domestic violence often come days after an actual attack, because victims must first find an opportunity to distance themselves from their abusers.

Evaluating domestic violence crime numbers at this point is difficult, not only because of the potential lag in reporting, but also because crime has fallen sharply in all categories

The LAPD logged 21% fewer reported crimes from March 1-25 than it did for the same period a year ago. But the number of reports for intimate partner assault — the most common type of domestic abuse crime — fell at a lower rate, dropping only by 7.4%.

That means that cases of intimate-partner violence last month accounted for a slightly larger share of overall crime than it did last year. Between March 1-25, about one out of every 13 crimes logged by the LAPD was for domestic abuse. During the same period a year ago, it was about one in 15, representing a 17.6% increase.

Det. Marie Sadanaga, who covers Downtown, observed an increase in the number of domestic violence-related calls her unit was receiving following the stay-at-home order.

“There is more fear right now because the perpetrator is still with the survivor at home,” she said.

Sadanaga urged victims who were still sharing the same space with their abusers to text rather than call 911. “If a victim is afraid to call us, they can text to 911 if they need help, but not many people know this,” she said.

According to the California Penal Code, domestic violence is abuse at the hands of an intimate partner, a spouse or someone with whom an individual shares a child. Det. Sadanaga stated that child abuse cases are redirected to a separate unit.

Sharing close quarters is not the only source of stress. The massive economic dislocation caused by the shutdown can also spark conflict. California reported 878,727 unemployment claims on March 28, a record high.

“We’ve seen that historically, in moments of crisis that have resulted in job loss and financial loss, the numbers of people experiencing domestic violence have increased,” said Amy Turk, the chief executive of the Downtown Women’s Center. “You obviously have more proximity to your abuser when you’re at home with them 24/7, which opens up a whole new level of danger, because you can’t even make that call for help.”

Social advocacy groups and women’s shelters are bracing for the potential of a pandemic-induced surge of violence.

Vanessa M., who requested to withhold her last name since she is a counselor for survivors, is a volunteer provider at the East Los Angeles Women’s Center.

“Unfortunately, our calls for domestic violence haven’t increased, because the survivors who are going through abuse are isolated with their abusers,” she said. “So, they don’t have a safe space within their house to contact us. We know that there is going to be an increase in calls through our hotline after the lockdown is lifted.”

She said the most intense period for domestic violence usually occurs around the holidays, but even then, there is a delayed response.

“We actually get the calls a week after, because by then, schedules are back to normal and the family members are out of the house,” Vanessa said. “That’s when the survivors have the chance to reach out to us. We are taking the time to make them understand that at the end of this lockdown, we are going to be here and we are gearing toward responding to those calls.”

The concern spreads far beyond Los Angeles. Mother Jones identified 13 cities and counties that have recorded an uptick in either 911 or hotline calls related to domestic violence, including Seattle, San Antonio and New York City.

While the wider notion of domestic abuse pertains to partner-on-partner aggression, children can also be caught in the crossfire. Yet, identifying that problem is harder than ever when schools are closed. Children who may be victims of abuse are less likely to come in contact with adults who might recognize and report the problem.

“One of the biggest mandated reporters of child abuse are actually schools, and those are obviously shut down,” said Amara Suarez of the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services. “That’s a huge source that has disappeared. I can confirm that the number of calls to our child abuse hotline has actually gone down.”

How we did it: We used publicly available data from the City of Los Angeles’ Open Data Portal. We used two sources: overall LAPD crime data, using the code for “intimate partner violence” to identify instances of domestic violence for our overall statistics, and data on service calls relating to domestic violence to identify the number of daily calls related to domestic violence for the months of February and March.

The LAPD does periodically update past reports with new information, which sometimes leads them to recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database. We try to update our reporting when new data becomes available.

Want to know more? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.

*This article was updated to include a more accurate description of service-call data.