Killings climb in LA during COVID-19

The number of murders in the City of Los Angeles has jumped 20% so far this year compared with last, even as overall crime has fallen as a result of the extended COVID-19 shutdown.

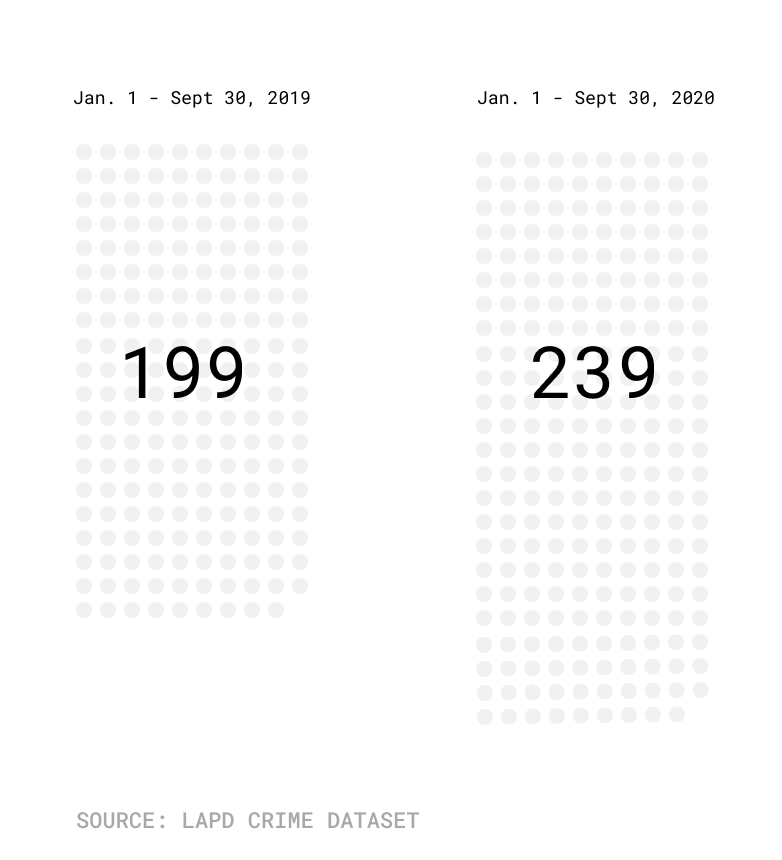

Between January and September, there were 239 people killed. In 2019 during the same period, the number of murder victims was 199, according to Los Angeles Police Department data. The increase in murders stands out against a 9.7% drop in overall crime in the city.

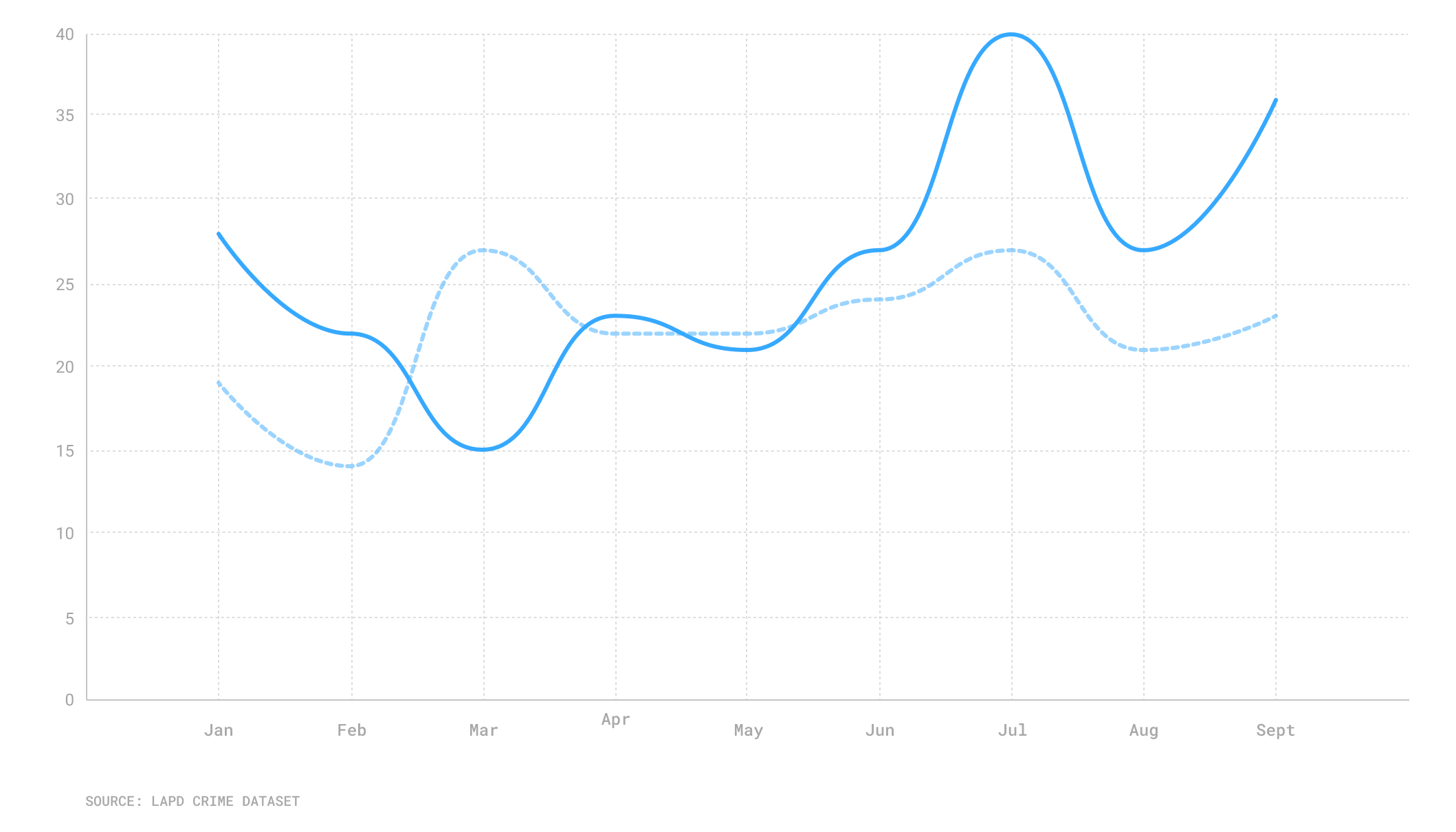

July was particularly distressing, with 40 reports of homicide, the highest monthly tally in at least a decade. It was a 48% increase from June, when there were 27 victims. In August that number fell back to 27, but jumped again to 36 last month. During the same time last year, the highest number of homicides in any given month was 27.

Homicides in Los Angeles 2020 vs. 2019

The pandemic has led to fewer people on the street, which has helped push crime down broadly. But other traditional deterrents to violence have also disappeared. “With COVID having everything closed, there are fewer mediations happening for a lot of people with no guidance and it’s causing a lot of friction,” said Curtis Woodle, a retired Los Angeles Police Department officer who worked for eight years as a gang intervention liaison.

The role of social media

Woodle said gang violence has evolved in the age of social media. “A beef could happen at a party or something they saw on Facebook,” said Woodle. “These things can grow into a war.”

Ben “Taco” Owens, an ex-gang member and now community intervention worker, said some homicides are now driven by “‘drill rap,’” a style of trap music that originated in Chicago in which rappers will use songs to promote the violence they are going to commit and “diss” rival neighborhoods.

“It’s an antagonizing form of rap between suspects and victims,” said Owens. “One week you can be rapping about how you’re going to shoot Johnny, but then Johnny will get that person first and it goes back and forth.”

Owens also said levels of violence were rising in part because of elevated financial stress from high unemployment brought on by the pandemic and the influx of guns on the streets that can now be ordered on the dark web and delivered to someone’s door.

“COVID has made life miserable for a lot of people,” he said. “People were already experiencing this in neighborhoods and the pandemic compounded things.”

Monthly homicide count, 2020 vs. 2019

Fewer police on patrol

Owens said the uptick in shootings that began during the July 4 weekend was exacerbated by the “blue flu,” when numerous officers called in sick, adding he believed there were roughly 300 calls made from the South Los Angeles area about shootings that weekend.

“That put folks on the edge,” he said. “People in South LA were asking if it was retaliation from the police due to the protests.”

Captain Paul Vernon, the head of the LAPD’s Compstat division, which analyzes crime data, said officers who usually patrol areas with high violent crime had been re-assigned to alternate duties, stemming from widespread demonstrations in May and June. In addition, officers also had been assigned to COVID-19-related work. That, he said, created more opportunities for offenders.

“Those who would perpetrate violent crimes know when the police are present,” said Vernon. “They take calculated risks to act and go in public armed.”

Vernon said that the number of shooting incidents that targeted groups of people had also increased, leading to more victims. “Twenty years ago, drive-by shootings were quite prevalent, but the rate at which persons were shot was low due to the inaccuracy of shooting from a moving vehicle and the distance to the victim,” he said, adding, “Walking up to a victim makes a shooting far more lethal, and when done into a group, the shooter may be more apt to shoot others to preempt someone from shooting back or to eliminate witnesses.”

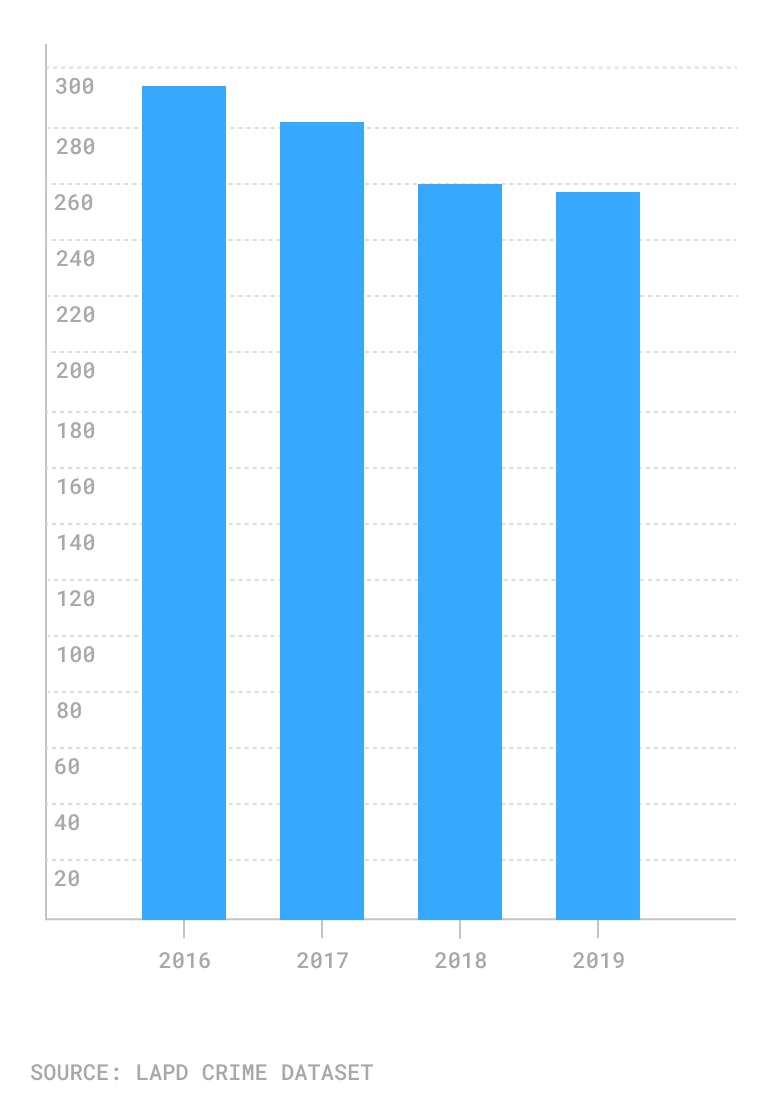

Vernon said the double-digit rise was “significant,” particularly as the homicide rate has fallen steadily over the past 30 years. Indeed, homicides dropped nearly 13% between 2016 and 2019.

Total homicides in Los Angeles, 2016-2019

Boyle Heights and Downtown both had 15 homicide victims during the first nine months of this year. Vermont Square saw the biggest increase, with 12 victims, up from three compared with the same time last year.

No outlet for grief

Owens, the community intervention worker, said another concern is the impact the pandemic is having on people who are unable to grieve when they lose a loved one to homicide because of social distancing. Research has shown the lack of rituals within communities that accompany death has caused additional stressors as grief in solitude has become widespread.

“People can’t say goodbye and let it out,” said Owens. “Funerals and memorials are gone for our community. Your friends and loved ones have to take it on the chin and continue with life. That is trauma that is bottled up.”

Owens said relationships between the police and community have come a long way in recent years, though they still have a way to go. He would like to see more funding for gang interventionists.

The 2019 State Budget Act made $27.5 million available in funding for California Violence Intervention & Prevention, formerly known as California Gang Reduction, Intervention and Prevention grants to cities and community-based organizations to support evidence-based violence reduction initiatives.

“We’re at a deficit because no one is really interested in funding gang interventionists,” said Owens. “How do you prove the conversations you’re having where you walked someone off a ledge are working? How do you document that?”

More than half of the state’s public school students are economically disadvantaged, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. A 2018 PPIC statewide survey found six in 10 Californians thought funding for their local public schools was not adequate.

According to a 2018 research paper in Preventive Medicine, there are nearly 100 liquor stores and bars in South LA compared with only 60 grocery stores for 1.3 million people, as reported by LAist.

How we did it: We examined LAPD publicly available data on reported homicides from Jan. 1, 2017 – Sept. 30, 2020. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. On occasion, LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.