Crime at ATM machines spikes during COVID

It is not only COVID-19 cases that are rising in Los Angeles: Crimes at automatic teller machines are also surging, a potential sign of growing economic dislocation.

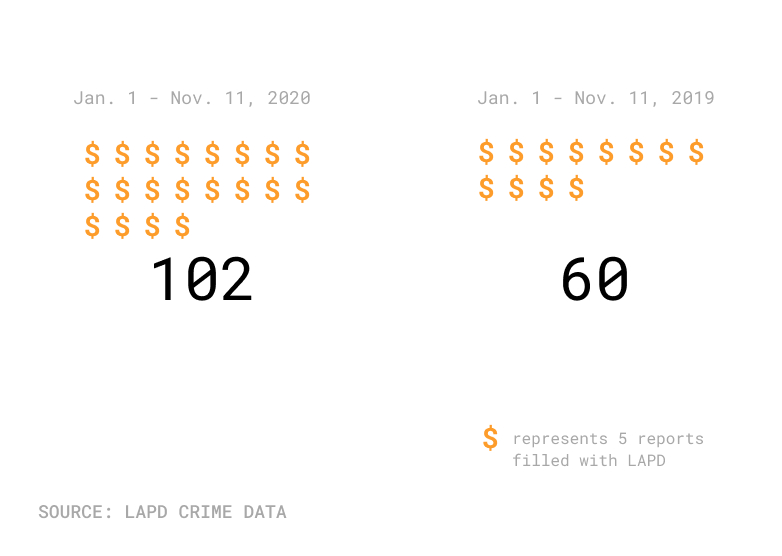

There were 102 reports of crime at ATMs from Jan. 1-Nov. 11, a 70% increase compared with the same time last year, when there were only 60 reports, according to Los Angeles Police Department data.

Crimes at ATM machines, 2020 vs. 2019

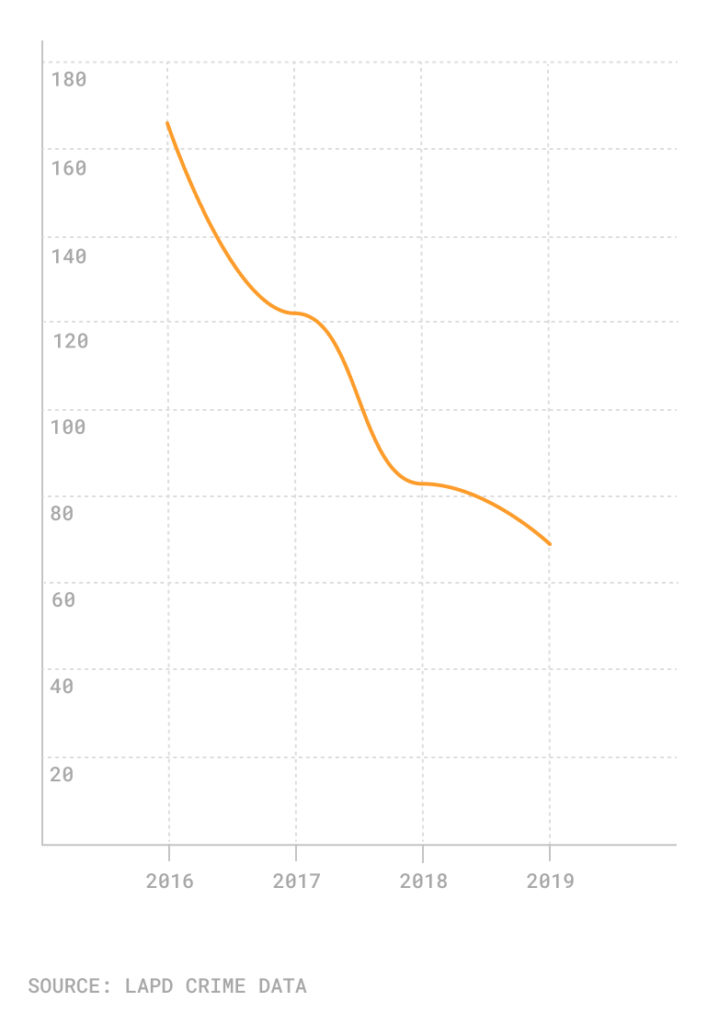

The 102 reports so far this year–which include offenses such as robbery and identity theft–surpassed the 69 incidents in all of last year. It also reverses a four-year trend, as ATM crime declined 58% from 2016-2019.

Annual number of crimes at ATMs, 2016-2019

Dr. Steven Graves, a geography professor at California State University, Northridge, who studies crime data, said it is no surprise that typical crime patterns have changed since the onset of the pandemic. He noted that fewer open businesses mean less opportunity for robberies and similar crimes. Indeed, robberies from Jan. 1-Nov. 11 are down 16% over 2019 levels, according to the LAPD.

Business shutdowns related to the coronavirus began in March, and the first uptick in ATM crime happened in May when there were 17 reports, more than double the eight that occurred in April. Incidents then decreased, with between seven and 10 crimes each month from June through September, before spiking again, to 19 in October. That compares with the eight crimes reported in October 2019.

Monthly comparison of crimes at ATMs, 2020 and 2019

David Tente, executive director for the U.S. and the Americas for the ATM Industry Association, said across the country there has been an increase in attacks on ATMs themselves.

“We did a survey this summer that found a lot of people were reporting vandalism at ATMs,” Tente said. “If you watch the news, you’ll see people attempting to break into them.”

Rise of the machines

ATMs were first introduced to the United States in the late 1960s. According to a report from the Arizona State University Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, the machines have led to crimes including robbery, identity theft (often utilizing skimming devices and stealing PIN codes), theft by data interception and vandalism. A spate of incidents prompted California state Sen. Charles Calderon, in a 1992 Los Angeles Times article, to call ATM issues “the crime of the ’90s.”

Of the 102 incidents this year, 11 were classified as a robbery or attempted robbery. The majority–56 incidents–were listed as identity theft. There were 58 male victims and 37 female victims, with the gender of the remaining victims unknown.

Van Nuys and Koreatown each had six incidents reported to the Los Angeles Police Department. Hollywood saw five incidents.

If an individual is the victim of a robbery at an ATM, a suspect will not be charged under federal bank statutes, since at the time of the robbery the money belongs to the customer, not the bank, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. However, if a perpetrator forces a victim to head to a bank and withdraw funds, then it could be considered a federal bank robbery.

Tente noted that while ATMs in bank branches are usually operated by the bank, 60% of machines, such as those in convenience stores and gas stations, belong to independent contractors. He said his association is working on a global crime data system that will allow banks and governments to contribute data to help spot trends in ATM crime.

While the rise in ATM crimes in Los Angeles may spark alarm, Graves believes the proliferation of cashless transactions will lead to fewer of these incidents in the future.

“I rarely carry more than about $20 around anymore,” said Graves. “I use my smartphone to pay when I can and the credit card to pay for other things. It will be interesting to see how criminals adapt to these changes and how the black and cashless markets evolve.”

The American Bankers Association recommends that people be aware of their surroundings when using an ATM, inspect the machine for possible card skimming devices, and have a companion if using a machine at night.

How we did it: We examined publicly available crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from Jan. 1, 2016-Nov. 11, 2020. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.