How bad is the pollution from the ports?

Julia Rozolis-Hill knows all about the epic backlog at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. The 21-year-old asthma sufferer’s symptoms began to worsen in August, as cargo ships anchored a few miles off the coast for weeks—their engines running—while they waited for a berth to open.

“I can instantly feel bad air quality. My lungs tense up and my chest feels tight,” she said.

Health experts have warned of the excess pollution created by port congestion. But measuring exactly how much more air pollution than normal is being generated is complicated. The Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach, both of which are required to report on air quality in the vicinity, have only shown a few days in which pollution levels exceeded state standards. The South Coast Air Quality Management District, which monitors air pollution across the region, recently estimated there is a 40% increase in port emissions since fall 2020 compared to normal operations. Still, even that increase does not put the ports above their legal air pollution limit.

That’s frustrating for Rozolis-Hill, who can feel the change with each breath.

“As soon as I take my first couple of steps outside I can feel the difference,” she said. “When the air quality is bad I need at least three different medicines, sometimes up to seven. If I lived in an area with no pollution, it would be just like one steroid.”

Air pollution is a cocktail of several pollutants, and the measurements can vary based on the weather, wind direction or even time of day. Although area residents claim they can feel the effects of worsening air quality, the ports haven’t crossed a legal threshold that would require them to limit activity.

Theral Golden, a member of the West Long Beach Neighborhood Association, who lives near the ports, knows the difficulty of quantifying an impact of pollution on one’s health. He suffers from a continuous runny nose and frequent nose bleeds.

“It’s like a cigarette smoker,” he said. “First you think, there’s nothing happening, but in 10 years you may have a little cough, and in 30 years you are really feeling bad.”

Supply chain problems

The backlog which has plagued the two busiest ports in North America for several months is both a cause and a symptom of the breakdown in the global supply chain. As the economy has picked up, and American consumers have ordered more goods online, the stream of container ships from Asia to the West Coast increased. However, the ports lacked the labor and space to handle the jump in traffic. As a result, there are currently around 70 ships just off the coast waiting approximately 18 days to unload their cargo. Until recently, the wait time was as long as 55 days.

In addition, the nation is gripped by a chronic shortage of truck drivers, who are needed to move the containers out of the ports and off to warehouses. All of this compounded a pollution problem.

The remedy to the backlog stands to make air pollution even worse, at least in the short term. The ports last month began to ramp up toward round-the-clock operations. That means more trucks running at all hours of the day, increasing the particulate matter in the air.

Exhaust fumes

Sylvia Betancourt, program manager for the Long Beach Alliance for Children with Asthma, says the problem at the docks has disrupted daily life in the area. She is especially concerned about children who suffer from asthma.

“The trucks, waiting to get into the port area, are now often parked on residential streets and in front of schools,” she said. “Local residents are now paying the price for this national problem.”

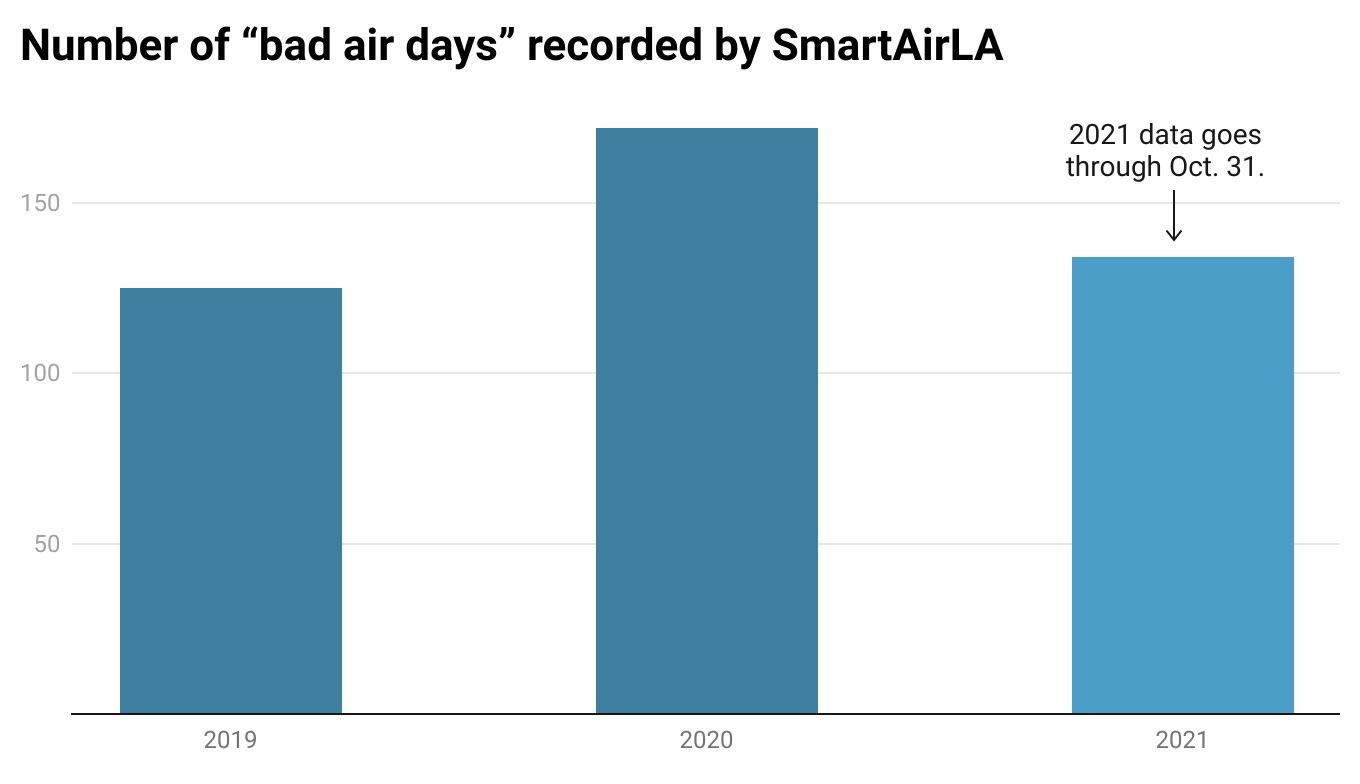

Ray Cheung, the founder of SmartAirLA, a community-based initiative that collects data on air pollution in the port vicinity, also bemoaned the health impacts of 24-hour port operations. SmartAirLA has created a tool called FightAsthma that collects real-time environmental conditions, reports of asthma symptoms from social media, and other data, such as traffic conditions. These are used to develop a rating that runs from one to five. Any level above four is considered a bad air day because it presents a high risk to asthma sufferers.

According to data from SmartAirLA, the asthma danger level has been excessive ever since traffic at the port picked up around August of last year. In 2020, almost every other day, or 47%, was a “bad air day,” where the asthma danger was at the top of the range. The first 10 months of this year already exceeded all the bad air days recorded in 2019.

Source: SmartAirLA

Counting trucks

The diesel-powered trucks that haul shipping containers to and from the port are a primary source of local air pollution. Each container is loaded onto a truck that transports it either to a warehouse or onto a train. By measuring the number of containers handled at the port, it is possible to gauge the increase in air pollution emanating from diesel trucks. The more containers, the more trucks.

Container volume at both ports has been increasing steadily, to record levels. Between January and October of this year, the number of containers handled by the ports increased by 20% over the same period in 2020.

Container volume at Los Angeles and Long Beach

(Container volume measured in millions)

Source: Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach

Although operating the ports on a 24/7 schedule could shave down the backlog, Dr. Sande Okelo, a pediatric pulmonologist and director for the Pediatric Pulmonary Asthma Center, says that may harm the health of area residents.

“The interests of the country in receiving goods and other materials through the port are now weighed against the interests of these small communities that don’t have many resources to combat this,” Okelo said. The health impact, he warned, could be dire. “If these kids will be exposed to pollution 24 hours a day, it means that there will be more children having asthma attacks, and having to go to the emergency room and even to stay in the hospital.”

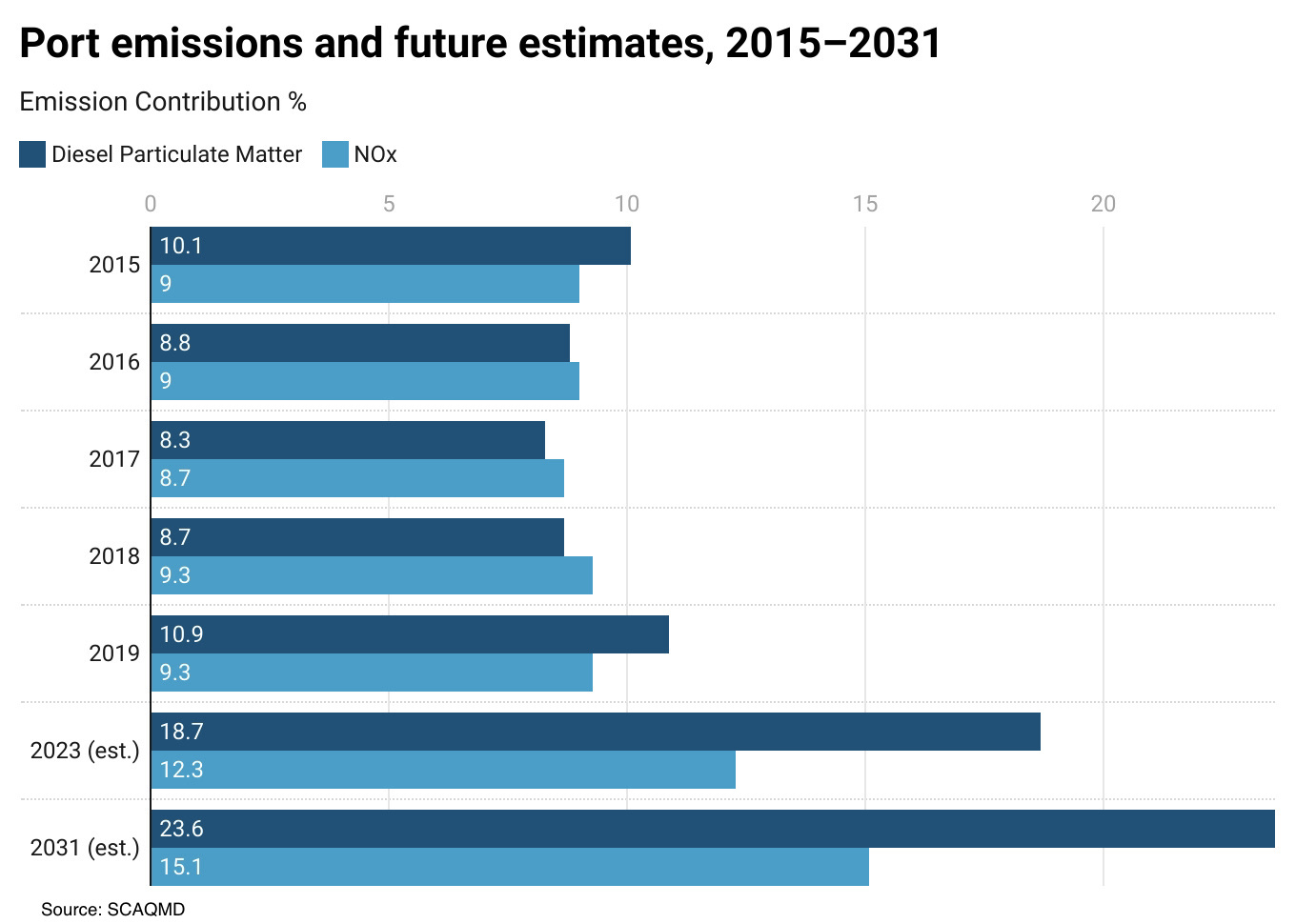

The looming issue is that the short-term fix will not address the longer-term trend that forecasts a notable increase in cargo over the next decade. The AQMD predicts that two major air pollutants, diesel particulate matter and nitrogen oxide, or NOx, will increase significantly as more containers arrive.

According to the Clean Air Action Plan, the ports have agreed to a process that will take them down to zero emissions for cargo handling equipment by 2030, and zero emissions for on-road drayage trucks serving the ports by 2035.

But even that doesn’t alleviate the problem. The fumes from idling container ships now produce the majority of the emissions. Environmental groups such as Earthjustice are pushing for stronger commercial harbor craft rules, worrying that the supply-chain crisis will slow the zero-emissions plan of the ports.

“With all this congestion and 24/7 operations, there has really been a slowdown in progress,” says Regina Hsu, an attorney at Earthjustice. “We don’t see how they will reach that.”

How we did it: We examined various air quality measurements from SCAQMD, the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and SmartAirLA, as well as container volumes published by the ports.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.