Did free Metro buses bring more riders?

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority launched a bold—if accidental—experiment: Would making buses free lure more riders?

On Jan. 10, 2022, the experiment is set to end, and the $1.75 bus fare will be collected again. So, did it work?

Answering that question is tricky because COVID-19 disrupted so many lives—and commutes. But Metro also inadvertently created a control group. While buses went free, the agency’s rail service kept its fares. In that way, it’s possible to compare how quickly riders returned to free buses vs. trains that continued to charge.

There are numerous caveats, of course. Figures may be uncertain because some jobs allowed for remote work and others did not. Additionally, many people’s choice of bus or rail is determined not by cost but rather simply what gets them where they need to go.

Free ride

Still, the data show that, in the immediate aftermath of the lockdown, bus riders returned more quickly than did rail passengers.

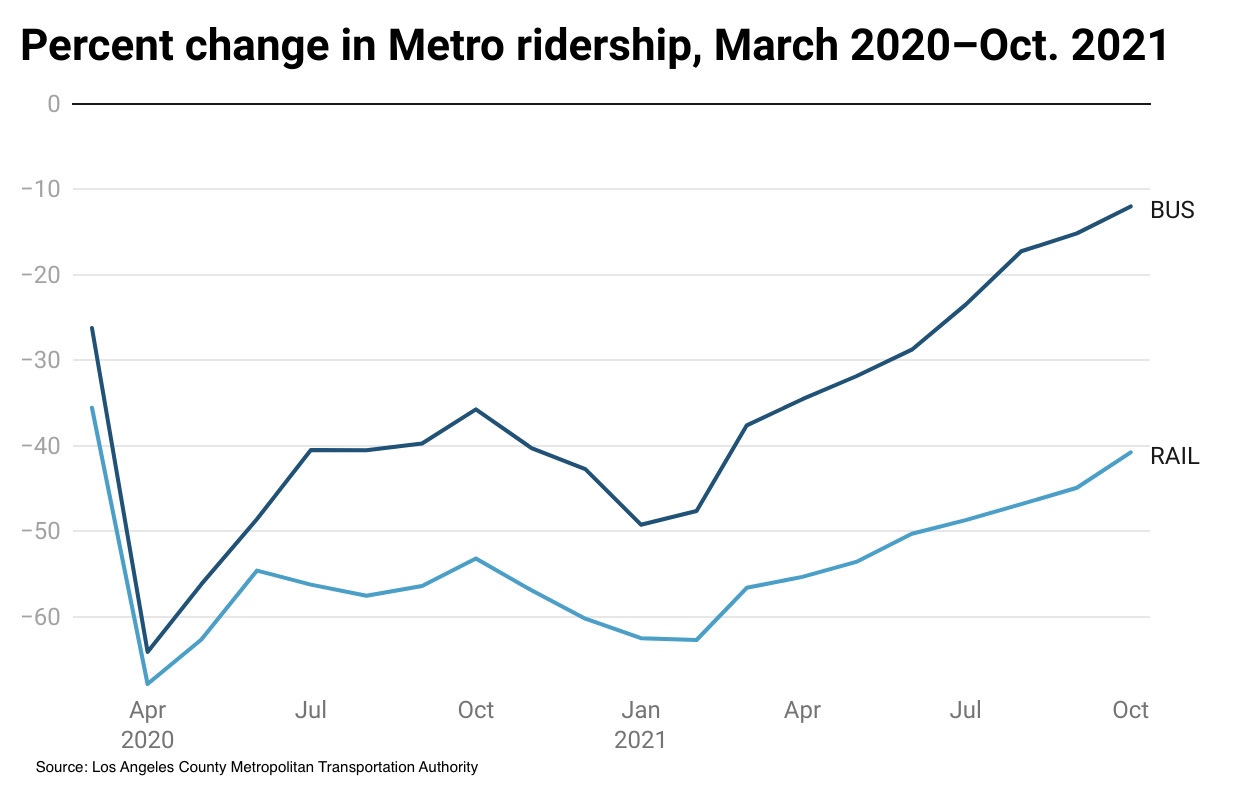

Of course, ridership on both systems nearly vanished in the first few terrifying weeks of the lockdown. In April 2020, overall ridership plunged 65% from the pre-pandemic month of February 2020. But by July, bus ridership was down only 40.5% from February, while rail was still down 56.3%. As time went on, the gap widened. In September, bus ridership was down by 15.2%, while the rail drop was 44.9%

This chart compares the percent change in monthly ridership on Metro’s bus and rail system to ridership volumes from February 2020.

The data are far from conclusive, as other factors impacted ridership, including the winter surge which began last December, the return of in-person school this August, and the rollout of vaccines. When bus fares return next month the additional data should provide more insight.

Some transit backers have called the fareless system a success. “We see free buses being a huge indicator that when public transportation in Los Angeles is made free, ridership increases,” said Alison Vu of the Alliance for Community Transit, which advocates for greater access to public transportation. She also anticipates a dip in ridership when fares return next month.

Metro officials caution that it is too early to draw conclusions. Dave Sotero, the agency’s communications manager, said the shifts in rider numbers were driven primarily by the gradual reopening of Los Angeles County after months of lockdown.

Bus and rail riders also fit different profiles, starting with bus users as a whole having lower incomes.

“Bus riders are our core ridership group who include people who have no other transportation option,” Sotero said. Most rail passengers, he added, “could roughly be categorized as more discretionary riders.”

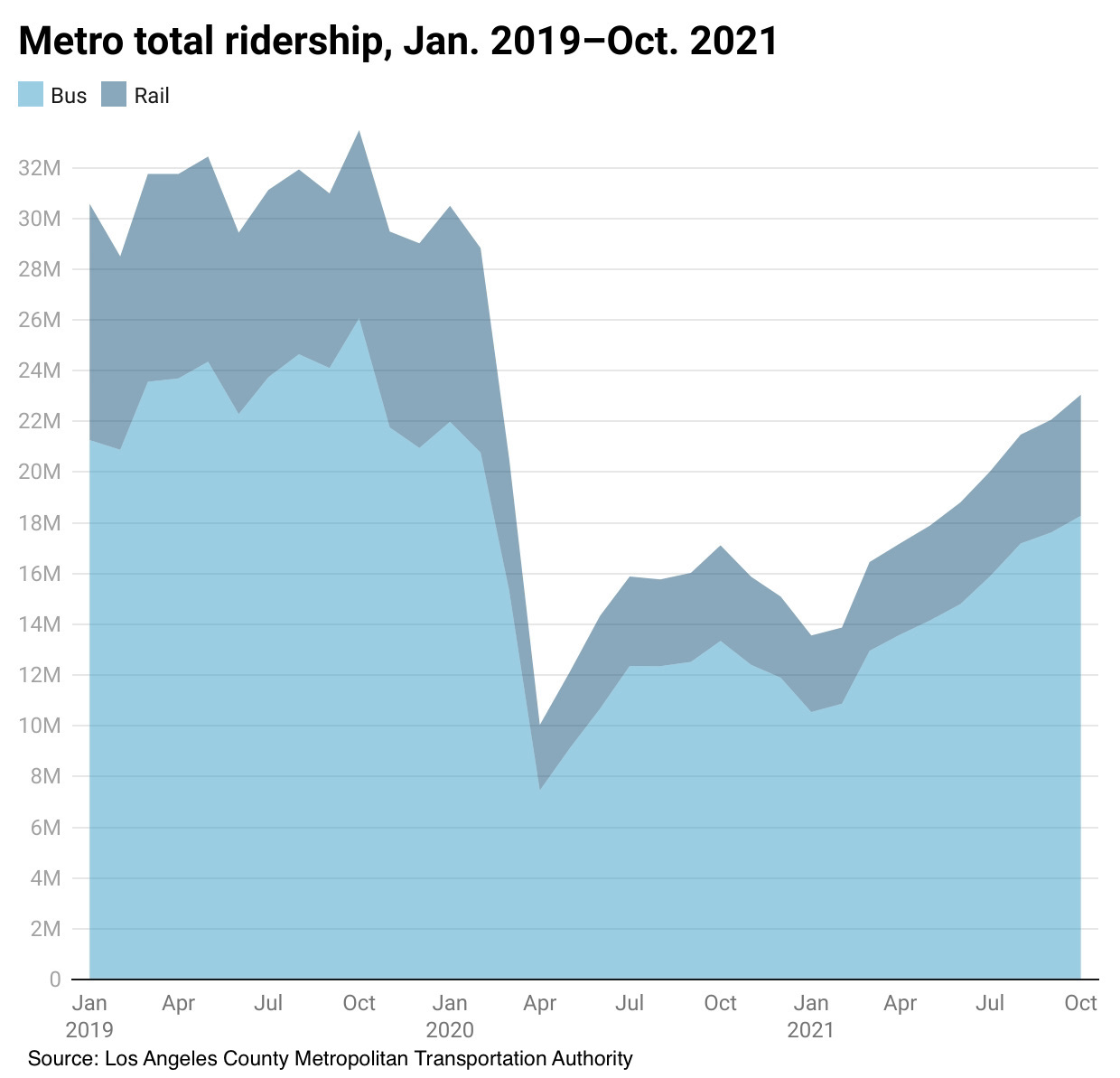

There are also far more people riding buses than trains. According to Metro data, in February 2020 the agency recorded an estimated average of almost 1.2 million systemwide riders each weekday. Of this, 871,000 took the bus, and 321,000 rode the rails.

Transit without the masses

Metro, which operates the nation’s second-largest mass transit system after New York, has long struggled to convince commuters to abandon their cars for buses and trains. Doing so would put a dent in two of Southern California’s biggest urban woes: traffic and smog. But even massive investments in recent years that brought more rail and bus lines have not significantly changed ridership patterns.

Metro’s previous chief executive, Phil Washington, who stepped down earlier this year (he was replaced by Stephanie Wiggins), had flirted with the idea of abandoning fares as a way of enticing riders onto the network. Last year he appointed a task force to investigate what it might take to make all buses and trains free.

“LA Metro has a moral obligation to pursue a fareless system and help our region recover from both a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic and the devastating effects of the lack of affordability in the region,” he told Metro’s in-house publication, The Source. “I view this as something that could change the life trajectory of millions of people and families in L.A. County, the most populous county in America.”

Washington’s thinking was that there were already numerous discount programs for low-income riders, people with disabilities and senior citizens. So, “why not rip the Band-Aid off?” asked Sotero. “The answer is, it hurts.”

The cost of free

A fareless system, the task force concluded, would be much too expensive. Only through copious amounts of emergency federal aid has Metro been able to maintain a fare-free bus network for the past 21 months.

Metro never formally made its buses free. Instead, on March 22, 2020, in order to encourage social distancing and protect drivers, it asked riders to enter from the rear door rather than pass through the narrower front door where fares are collected. The end result was the same—no one was requiring fares.

Roderick James, a 64-year-old environmental coordinator and maintenance supervisor, takes the 53 Metro Local to get to work. Before the pandemic, he spent about $25 a month on fares. Then he noticed that the driver wasn’t collecting fares.

“They probably could have just given free rides to the citizens,” James said. People who ride the bus, he added, “have to ride the bus. They have to go to work, go to college.”

Cities have long experimented with free transit systems. In California, the City of Commerce, with a population of around 13,000, has the oldest free bus system, dating back to 1962. In 2019, voters in Kansas City approved a plan to make it the first major U.S. city to offer free fares. The bus system’s chief executive, Robbie Makinen, credits the move for keeping ridership fairly steady during the pandemic.

Metro is trying to create a soft landing for when fares return next month. It has streamlined its “Low Income Fare is Easy,” or LIFE program. Applicants no longer need to produce proof of low-income eligibility, and they receive $26 off what would otherwise be a $100 monthly pass. Many K-12 students can also ride free.

“We don’t want to go back and make it a shock to people,” said Sotero.

How we did it: We examined monthly ridership data for both rail and bus from the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority for the past three years.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la