Supply-chain logjam becomes air pollution nightmare

Just about everyone is feeling the impact of the supply-chain crisis. The people of Wilmington are breathing it.

Since the longjam at the nearby ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach began last fall, the quantity of dangerous pollutants, such as fine particulate matter, or PM 2.5, and nitrogen oxide, or NOx, have frequently crested above maximum allowable federal standards and into dangerous levels.

Port officials have scrambled to come up with ways to stagger the number of cargo ships waiting for a berth, such as requiring them to anchor many miles from shore until space opens. But air-quality monitoring data shows that the impact on local air quality, at least in the short term, has been minimal.

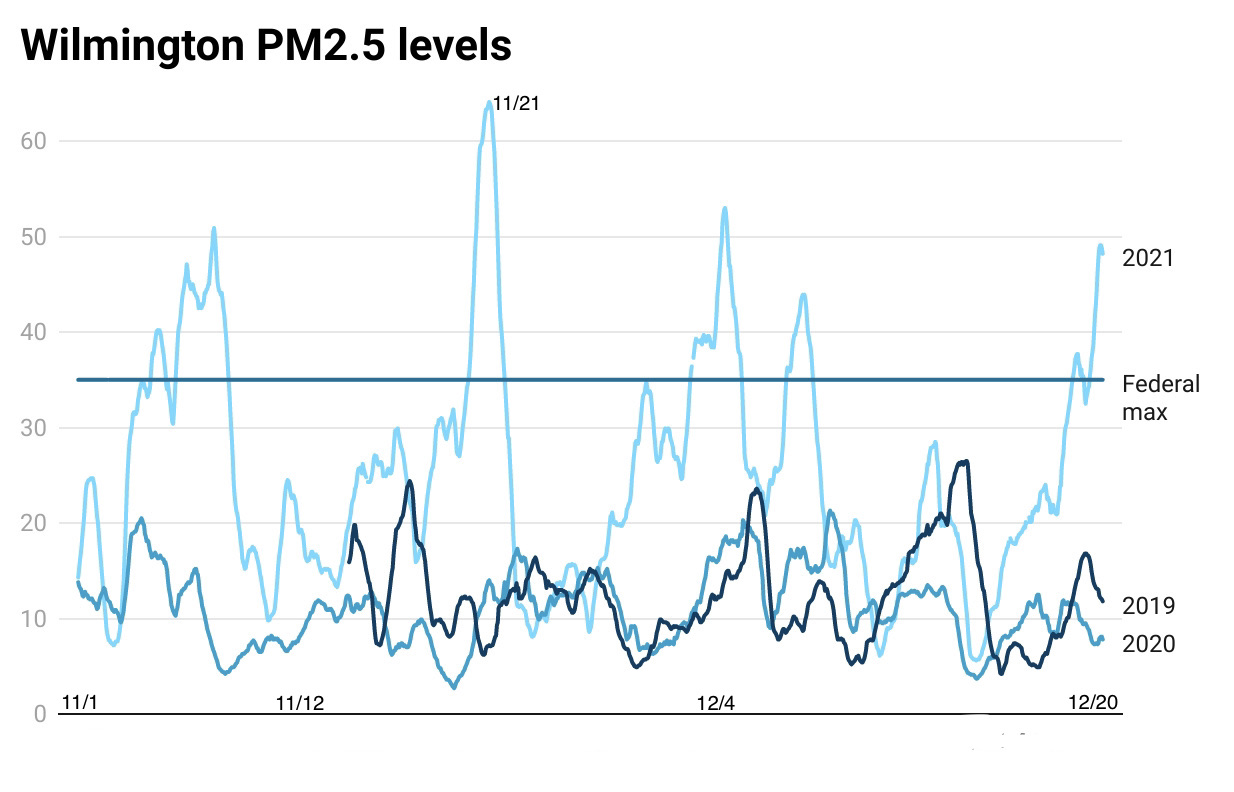

Residents of Wilmington and surrounding areas are still inhaling dangerous levels of pollutants, many of which are produced by the dirty “bunker” fuel spewed by the cargo ships. In November, PM2.5 levels rose above federal standards on eight separate days. So far this month, they have crossed that level seven times. On Nov. 21, the level hit above 64 micrograms per cubic meter, nearly twice the maximum federal allowable level. Both November and December this year are significantly higher than the same months in previous years.

Levels of PM2.5 pollution recorded at Wilmington from Nov. 1-Dec. 20 during each of the past three years. (Data from 2019 was not available prior to Nov. 14.) Source: The Port of Los Angeles, Port of Long Beach.

Wilmington, with over 50,000 residents, was already one of the most environmentally burdened areas in Los Angeles. “We are number one in so many things that it makes you cry,” said Jesse Marquez, executive director for Coalition for a Safe Environment, an environmental-justice community organization in Wilmington. “We have the ports. We have refineries and we have landfills, you name it.”

Marquez, a lifelong resident of Wilmington, says that recent months have been especially difficult. He has suffered from asthma attacks, as have his two sons.

According to data provided by SmartAirLA, a community-based initiative that collects data on air pollution in the port vicinity, the number of asthma danger days in November were at a record high, 24 out of 30. That was much worse than the same period in two previous years, which recorded 11 in 2020 and 17 in 2019, respectively. Data for December is not yet available.

“Since the supply-chain bottlenecks, our analytics see a surge in asthma danger in the port region that is higher than historic levels,” said Ray Cheung, founder of SmartAirLA.

Referring to the dangerously high air pollution readings around Wilmington, Christopher Cannon, the director of environmental management at Port of Los Angeles, said, “We have seen it and been carefully monitoring it. And we are currently studying to determine what the effects are.”

According to Cannon, the waiting cargo ships could be producing as many as 20 tons of NOx per day. According to an analysis by the California Air Resources Board, that’s roughly the equivalent of the amount produced by 13 million cars.

“We are very concerned about the effects of the anchorages on the environment,” Cannon said. “And not only about people’s asthma and other effects on people, but also greenhouse gas emissions and an extraordinary increase in greenhouse gas emissions that come from the ships just sitting there.”

Under the new system organized by the ports, as soon as the vessels leave Asia, they are given a time slot for when they can unload in Southern California. This way they don’t have to rush across the ocean, burning more fuel along the way, and that they can anchor around 150 and 200 miles out before entering the harbor area. Cannon said this system has so far decreased the number of the ships at the ports by almost 60%.

Environmental groups such as Earthjustice believe that moving the ships further offshore may alleviate some of the increased emissions from the shipping congestion, but it does not resolve the larger issues of port pollution. Instead, vessels at anchor are continuing to pollute in other coastal areas, such as Ventura County, to the north.

“Prior to the pandemic, the ports were the largest fixed source of pollution in the region and this continues to be the case,” said Regina Hsu, an attorney at Earthjustice. “Instead of cleaning up operations, the ports have maintained their focus on growth and expansion.”

In fact, both ports project a sharp increase in the amount of vessels coming their way in the coming years.

Cannon, from the Port of Los Angeles, conceded that the new plan does not solve the pollution problem, but he insisted it does partially mitigate it. “It does not mean that the emissions have gone away,” he said. “But we hope that it will result in reduced impacts on shore.”

Long before the logjam began, both ports had committed to a Clean Air Action Plan that was supposed to lead to dramatically lower levels of pollution by requiring cleaner trucks to move cargo and other measures. But the current supply-chain backup has now made those goals more difficult to achieve.

“In the near term, our emissions will go up, no doubt about it,” Cannon said. “But I hope after this situation gets rectified and then we’ll be back and see a drop again.”

How we did it: We analyzed three years of air quality data provided by the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach, as well as data compiled by SmartAirLA.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.