Pandemic pushes up rents in inland enclaves

Over the past five years, Amanda Ventura watched the rent on her modest apartment in Pomona climb from $995 to $1,350, with another increase coming next month. When she began looking for a cheaper place reality set in.

“What’s funny is that we found a place for one-bedroom and one-bathroom at the same price as what we are living in, a two-bedroom and two-bathroom,” she said.

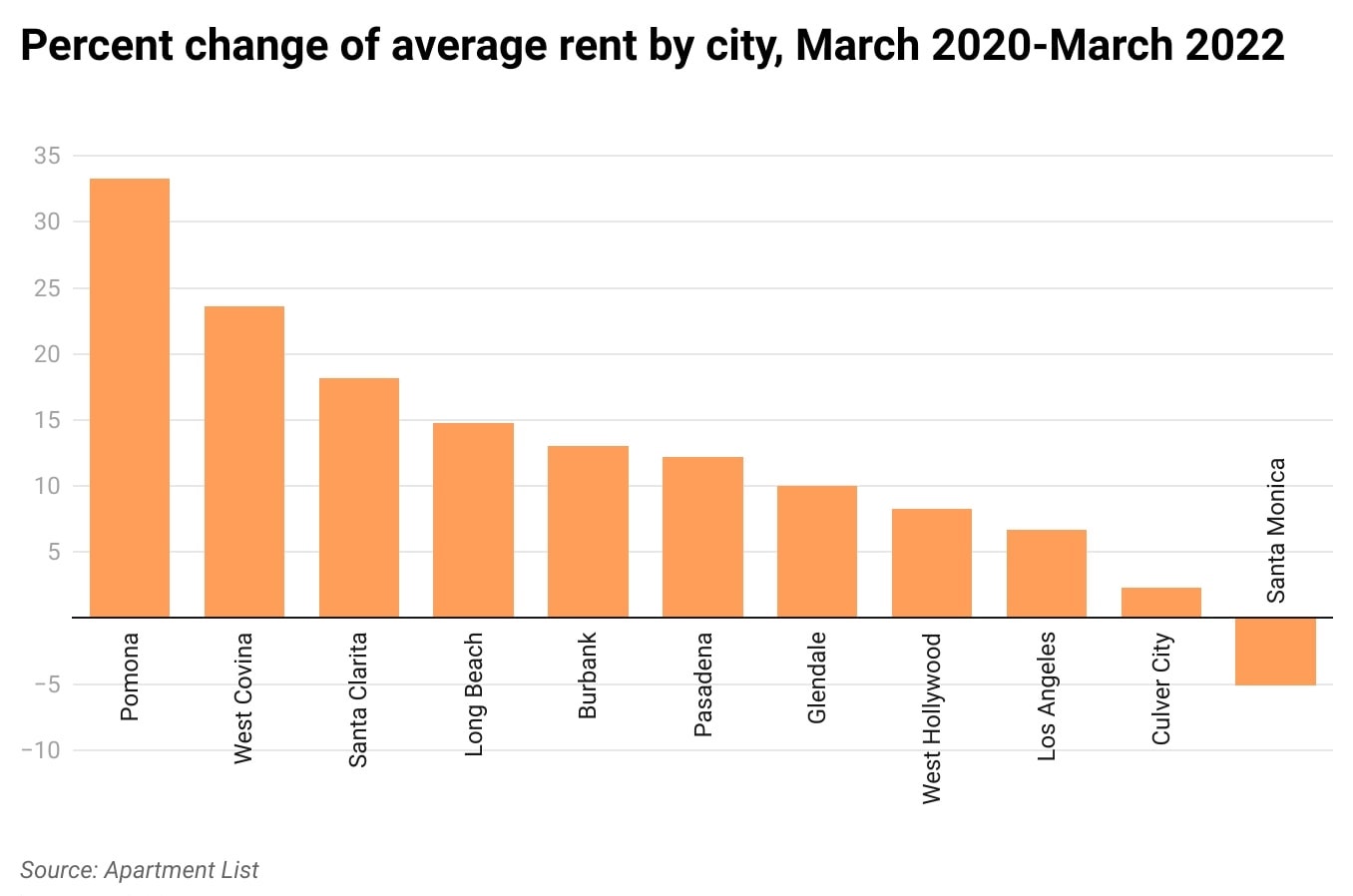

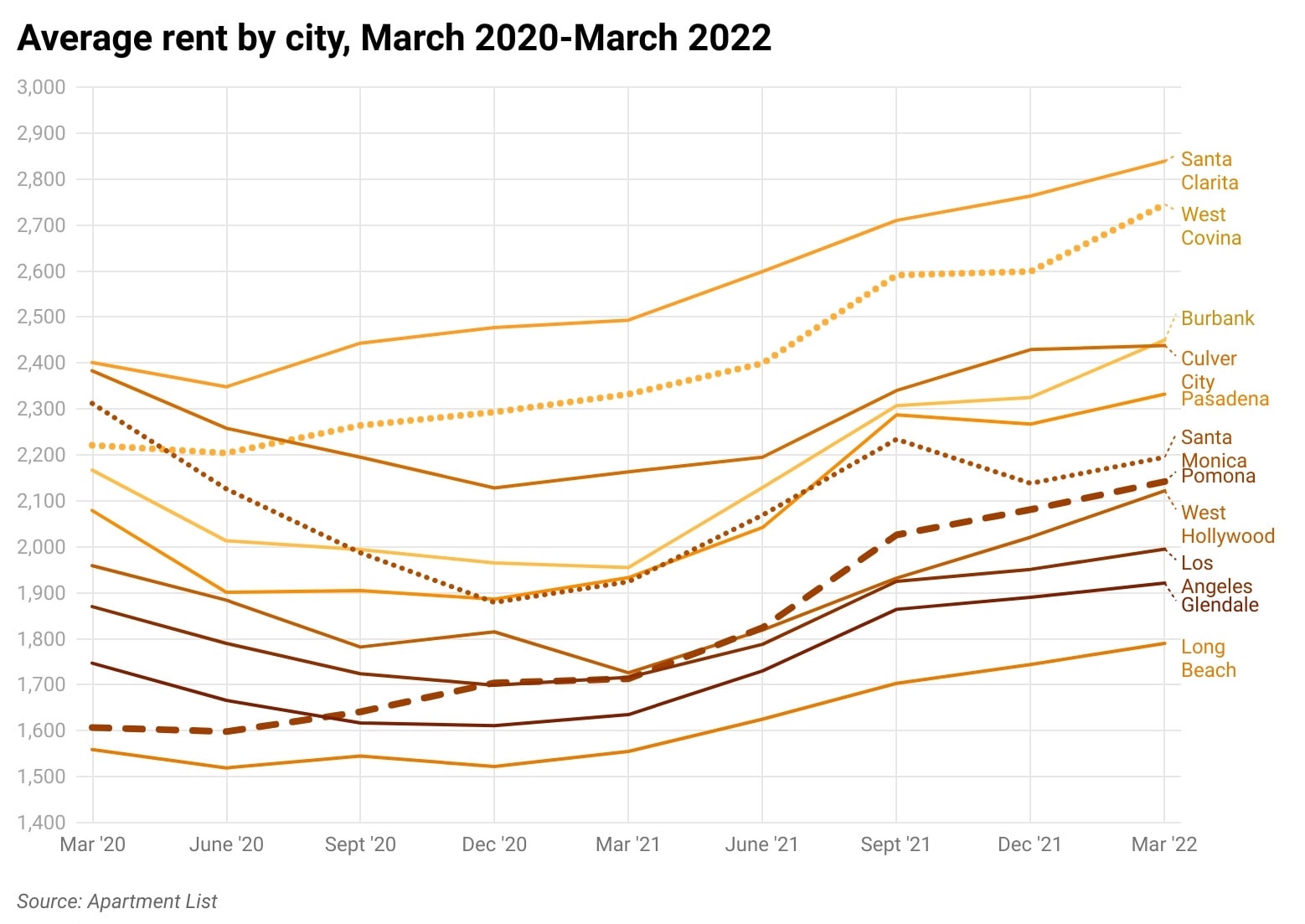

The pandemic worked like a pressure cooker on an already overheated Los Angeles County housing market, pushing average rents up 12.1% since the onset of the lockdown in March 2020, according to data compiled by Apartment List, an online rental housing marketplace.

And in a reversal from earlier trends, the steepest increases hit inland enclaves, not coastal cities. That, in turn, is rapidly reshaping communities that had previously dodged some of the worst aspects of Los Angeles’s chronic housing shortage.

Over the past two years, Pomona, a city at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains 29 miles east of Downtown, saw rents surge by 33.3%, the highest among the 11 cities Crosstown surveyed. Longtime residents are now being sucked into the same affordability crisis that has plagued other parts of the county. Pomona has a median household income of $62,407 and a 17.3% poverty rate, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

West Covina, another suburban city located roughly 12 miles from Pomona, saw the second highest overall rent increase, at 23.6%.

[Get crime, COVID-19 and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

Santa Monica on par with Pomona

The beach city of Santa Monica was the only place to register a decrease during the pandemic, with rents falling by 5%. (Santa Monica maintains some of the strictest rent-control regulations in the state.) It has a median household income of $98,300 and a 10.1% poverty rate, according to the Census Bureau. But the city’s overall rent for the month of March was only $53 higher than Pomona.

Similarly, dense, urban areas such as West Hollywood and Culver City saw moderate increases, while suburban communities including Santa Clarita saw steeper hikes, as Californians fled coastal Los Angeles for inland communities.

(Private services such as Apartment List, Zillow and Rentometer often rely heavily on recent transactions; renters who have been in a property for several years, and are therefore likely paying a lower rent, might not be fully captured in the data.)

“You’re getting people moving in with the high paying jobs who push out lower income people, some of whom leave the state altogether,” said Richard Green, a professor of public policy and the director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate.

During the pandemic, well-educated and high-skilled workers left urban neighborhoods in search of more space and greenery.

“The people who are making $200,000 a year are living in the houses that used to go to people who are making $50,000 a year,” Green said. “You have to provide lots of housing so that the people who make a lot of money won’t push out people who don’t.”

Years of meager housing construction, combined with demographic changes, have supercharged the real-estate market.

“We just haven’t built remotely enough housing here in a very long time,” Green said, adding that there are a historically large number of “empty-nesters” who have way more housing than they need but are unwilling to move.

“When you’re in your 60s, you just don’t want to do that,” he said.

Priced out and displaced

The change in Pomona has occurred on hyperdrive. It has the highest poverty rate of the 11 cities in the survey and has long been a refuge for low-income people willing to brave the commute to Los Angeles.

“Rents traditionally have been 10-30% lower in Pomona, pretty much than anywhere else,” said Catherine Tessier, who works in real estate management in the area. “Now, the problem is, it’s catching up.”

Longtime residents are in danger of being displaced, said Jesus Sanchez, a Pomona resident and staff member with Gente Organizada, a community-led nonprofit that has been a vocal supporter of rent control in the city.

“A lot of folks are fighting to stay out here,” he said. Fed up with the steep rent hikes, many are moving further east into San Bernardino County, and some are leaving the country altogether, Sanchez added.

“There’s a handful of folks that we know within our network that have actually gone back home to either Mexico or Central America,” he said.

How we did it: We compiled monthly average rent data provided by Apartment List from across Los Angeles County for the period from March 2020-March 2022.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.