Did L.A.’s experiment with free buses work?

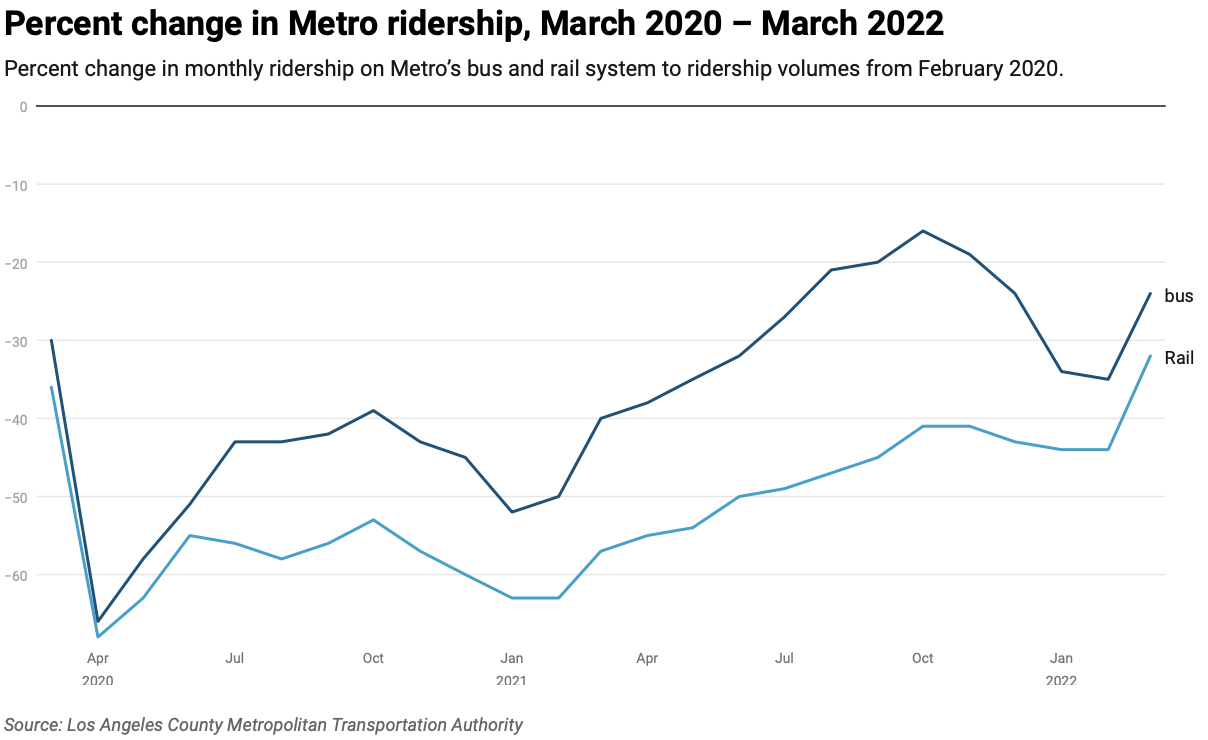

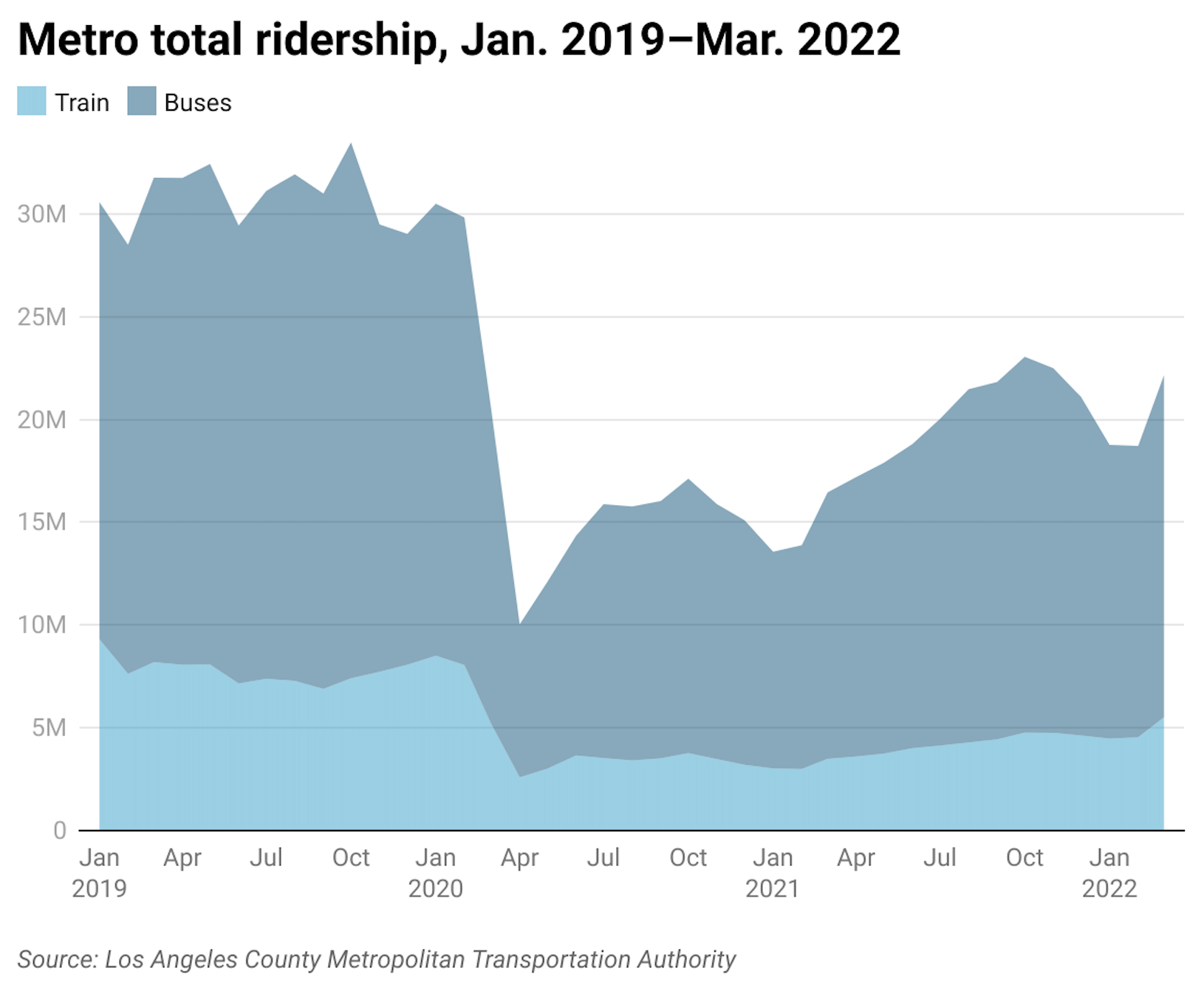

For almost two years, as the pandemic raged, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority made its buses free. Ridership, for the most part, climbed steadily, and at a faster rate than on trains, which still charged a fare.

Some hailed the experiment as proof that free transit is a surefire way to draw riders. So what happened when the fares came back on Jan. 10?

Bus ridership dropped 10% from the prior month. Rail passengers barely budged. Those numbers held steady in February, as well. By March, however, as gas prices rose, riders flocked to both bus and rail.

Does that prove that free fares drive people to public transit? Making a conclusive case is tricky because there were so many other factors at play, such as the rapid spread of the Omicron variant in early January, followed by spiking gas prices in March.

Economic animals

However, some see the policy as playing an influential role. “People are economic animals,” said Prof. James Moore, director of the USC Transportation Engineering Program. That applies to free fares as well as rising gas prices. “If they can’t afford to fill their automobile gas tanks, they still have to get to work,” Moore added.

Low-income riders, many of whom can’t afford cars, make up 70% of Metro’s ridership. “Transit riders are to some degree captives,” said Moore. “They’re on these vehicles because they don’t have much in the way of alternatives.”

That’s even more true for bus riders than train passengers. “You do tend to see discretionary riders using rail more often because maybe they work at a specific location and the railway goes straight there,” said Metro Communications Director Dave Sotero. Discretionary riders have the option of driving, in contrast to captive riders who must use transit because they don’t own cars.

Another factor influencing the numbers, Sotero notes, may be a gradual return to the office for some workers as pandemic restrictions lift. “I have to go into work three days a week now, and I could work from home twice a week,” he said. “But that means I’m riding Metrolink three days a week, whereas I didn’t ride it for two years in a row during the pandemic.”

Even though bus operators are supposed to be collecting fares, enforcement remains lax. Mendy Kong, a 21-year-old student who commutes to school by bus, described how some passengers still hop on buses through the back door and not pay.

“Drivers are going to get paid either way whether you’re paying or not, so for the most part they’ll let you on if you are struggling,” Kong said.

Going Fareless

Part of why Metro was able to go fareless in the first place was thanks to, well, taxpayers. Los Angeles County voters passed Measure M in 2016. The local sales tax will generate $120 billion for Metro over the next four decades, a situation unique from other U.S. transit authorities. Bus and train fares then make up about only 15-20% of Metro’s annual operating funds, Jacob Wasserman, a research project manager at the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies, told KCRW.

“It’s a small but important source of revenue for the agency, and, at this point, we can’t afford to provide free rides for the entire populace of L.A. riders,” Sotero said.

Still, that doesn’t mean Metro has given up on a fareless future.

It has a program called “Low Income Fare is Easy,” or LIFE, which provides discounts and free 90-day passes for first-time low-income riders.

“We’re looking for additional funding opportunities to potentially provide free fares for riders in the future,” Sotero said. “So we haven’t abandoned the idea, but it is going to require that we identify other funding sources to make it happen.”

Other cities, both in the U.S. but mostly abroad, have experimented with free transit systems. In California, the City of Commerce has a free bus system that dates back to 1962, one of the few free bus systems in the country.

Kong, the student, was able to qualify for Metro’s LIFE program, making bus rides free for them even after fares were reinstated in January. However, the express bus Kong takes as part of their commute is not included, and costs $2.75 one way.

“If you think about it, at least $2.75 a day, it adds up,” said Kong, who now spends around $25 a month on public transportation and has to budget for the extra cost.

“Free fares are important to me because I don’t want to pay money to get around,” Kong said. “[Transportation] is a basic human right.”

How we did it: We examined monthly ridership data for both rail and bus from the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority for the past three years.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.