‘Rents just went crazy’

Los Angeles resident Lindsey B. is working three gig jobs to cover the cost of a two-bedroom Airbnb for her, her 13-year-old daughter and her father who is unable to work.

Until March, she had been living in a three-bedroom apartment, paying $3,200 a month. But when her rent went up by $600, she was forced to move out. Her plan was to stay in the Airbnb for three months until she found a new place. It’s been five months and she sees no end to it. (Crosstown removed the interview subject’s last name after initial publication in order to protect the person from repercussions.)

“I’m struggling and I don’t know what to do. I feel like I have one foot in homelessness and one foot in stability, and I could fall either way,” she said. “I can’t go to another state. I don’t have family. I don’t have anybody to help. It’s me and me only.”

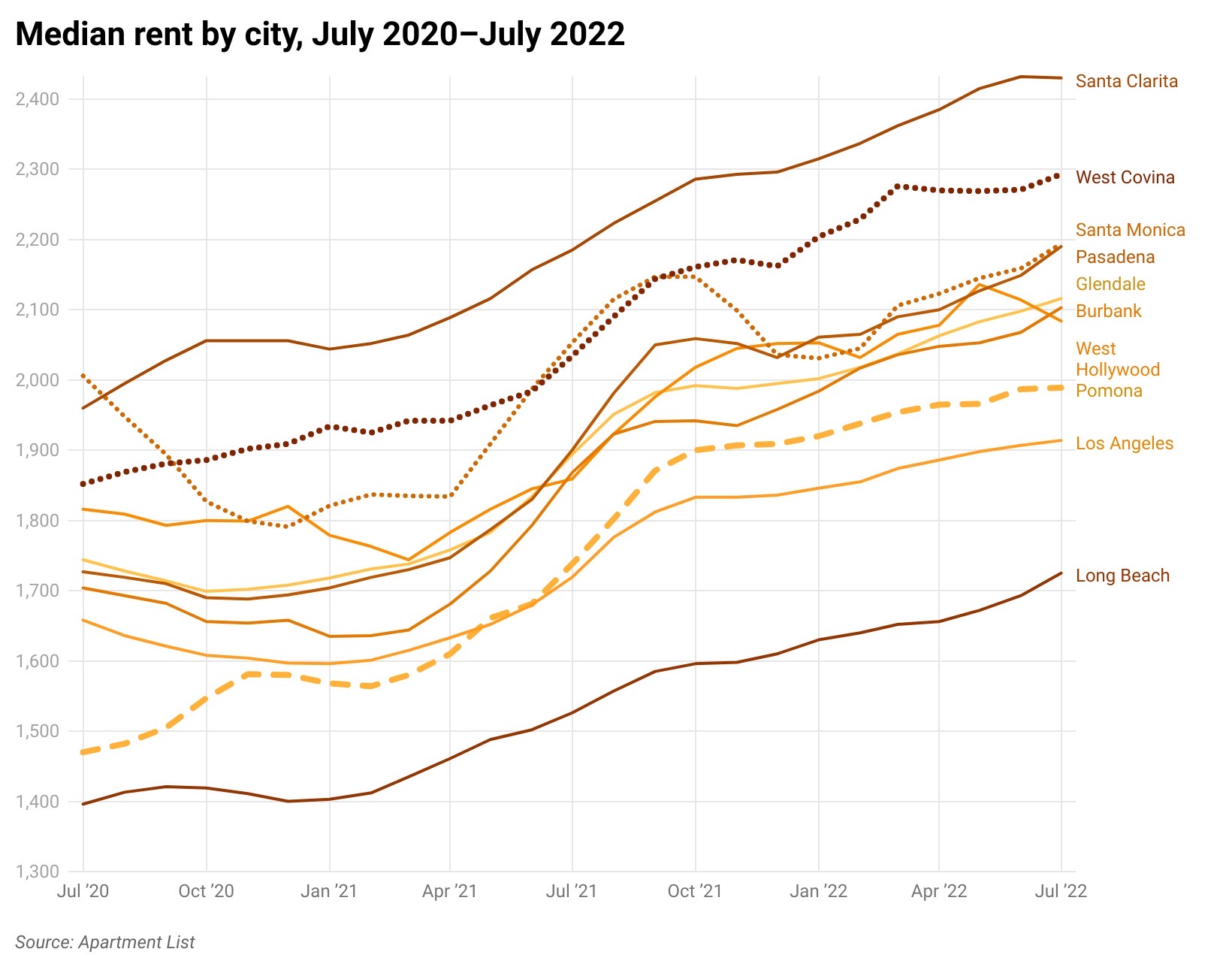

The average rent for new leases in Los Angeles County climbed 18% over the past two years, according to Apartment List, an online rental housing marketplace with data stretching back to 2017. In July 2020, the average rent was $1,651. This past July, it was $1,950.

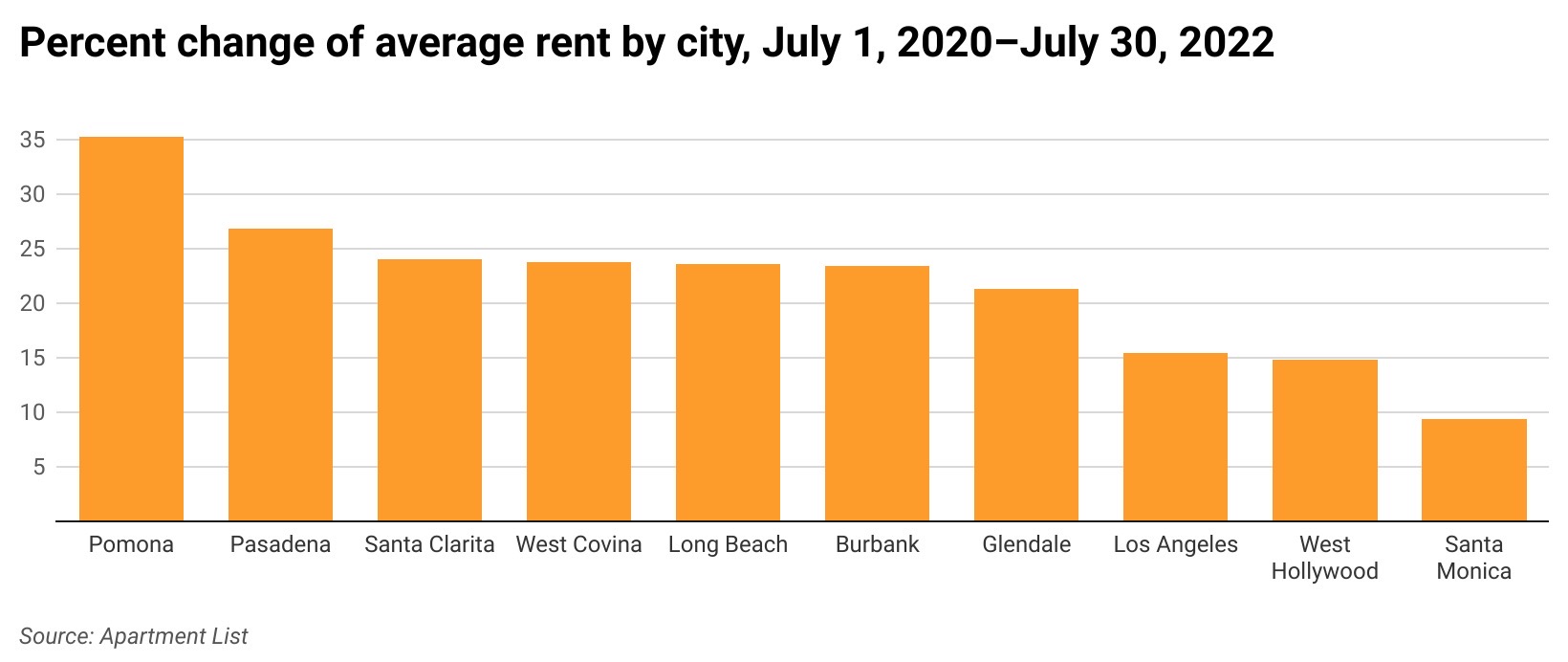

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, the market value for rent dipped, declining until 2021. Then it began creeping up again. In many places, the rise has surpassed 18%. Pomona, for instance, has seen a 35% increase in the past two years.

In Pasadena, there’s been a 27% increase and in West Covina rent has jumped 24%. Of the 10 major Los Angeles cities surveyed by Apartment List, Santa Monica has stayed the most stable, increasing 9% in the past two years.

One apartment, 20 applicants

“Before the pandemic, [rent] would increase maybe 5% or so a year on average,” said Sarah Gillen, a property manager at Utopia Management, which oversees properties in Los Angeles County. “But we have a tenant who moved out and when we went back to reevaluate, the market rents just went crazy. They were jumping like $300-400.”

She said that they would receive as many as 20 applications for one unit, with some people offering to pay above the asking price. A one-bedroom that would have gone for $1,200 three years ago now rents for $1,700.

[Get COVID-19, crime and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

With inflation at a 40-year high, an affordable housing shortage and statewide rent increases set to hit many residents, it’s not just cost-burdened Angelenos who are worried by this trend. Community organizers and experts are concerned about how this could impact everything from the labor market to homelessness.

Gary Painter, the director of the USC Homelessness Policy Research Institute, said that for folks with low and moderate incomes, the past two decades have shown a discouraging trend in rent relative to income.

“Rents have consistently gone up faster than those household incomes, which leads to a greater share of their income being dedicated to rent,” Painter said. “People are facing, in some cases, quite tragic choices about whether to eat healthy meals or pay the rent, to pay for medicines or pay the rent…. When you do face an unanticipated bill, you may not be able to pay your rent and therefore you could actually lose your house.”

Of the 10 major Los Angeles cities surveyed by Apartment List, seven reported the highest average cost to rent this past July.

Even prior to the pandemic, three-fourths of surveyed households in the city of Los Angeles were rent-burdened, meaning they spent over 30% of household income on rent and utilities. Nearly half were severely rent-burdened, spending more than 50% on rent and utilities, according to a USC study.

With every $100 increase in median rent, there’s a 9% increase in the estimated homelessness rate, according to a report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

“The places where rents are going up much faster than people’s incomes are also places where you’ve seen the most drastic increases in homelessness,” said Painter.

In order to address the issue, Painter argues, Los Angeles must significantly increase its housing density—fewer single-family homes, more apartment blocks. But that will take time. Until then, he says there is an urgent need for subsidies for people who spend more than half of their income on rent.

Some rent hikes are changing the fabric of specific communities, displacing residents who had long depended on their area to be an affordable option. The 35% increase in Pomona, for example, is forcing some residents out. (Although, some good news for Pomona residents: The city enacted a long-awaited 4% cap on rent increases early August).

‘No social life, just rent’

The problem stretches beyond Los Angeles County. Anaheim resident Brooke Soup is about to move out of her one-bedroom apartment because she can’t afford it anymore. Her rent has increased nearly 17% since the start of the pandemic, and as someone working two minimum-wage jobs and living paycheck to paycheck, she’s reached a breaking point.

“I’m actually moving out next month with my boyfriend. We weren’t really ready to move in together, but it’s just gotten to the point where I don’t have a choice,” she said. “Taco Bell is a luxury…. All my time just goes straight to having a job to be able to pay my bills, to go back to work to pay my bills, to go back to my house to go back to work. That’s all it is. And I’m noticing that from everyone. No social life, just rent.”

Despite feeling the squeeze of rising rent and no disposable income, Soup does have another perspective. Because her father is a landlord, she’s seen firsthand what’s pushed him to raise rent. For him, she said, decisions are a combination of what is fair, what is legal and what is necessary in response to rising maintenance and other costs.

Not all landlords are in that position. Gillen, the Utopia Management property manager, has worked in the industry for seven years, and said that although there are some small property owners who have felt the squeeze from nonpayments during the pandemic, and some who even sold their properties before it got too bad, most landlords raise rent to “jump on the bandwagon.”

“I had a guy who wanted to increase his tenant $500 a month, because down the street they were doing that,” Gillen said. “Because he hears other people getting all these crazy rents and wants to do the same.”

Gillen said that when someone moves out, they will also raise rent to market value—so long as the units aren’t rent controlled.

“Those are the ones that are really pushing, because they don’t have to,” she said. “They’re not stuck with that rule where they can only go up 5% plus the cost of living.”

How much can landlords raise the rent?

But across California, starting Aug. 1, there was a change to how much landlords can raise rent — making it likely that even more owners will get pushy.

California landlords are permitted to hike rent by as much as 10% this year. Since 2019, the rule has been that landlords can raise rents by 5% annually plus the rate of inflation—with a 10% cap. Inflation has pushed California to hit that maximum rent increase.

Shanti Singh at Tenants Together, a statewide renters’ rights organization, said she believes that the permitted increase will make housing more difficult for many Angelenos.

“It will accelerate displacement, and also grow our homelessness crisis, if we don’t step in and do something about it,” she said.

There are some places that can exceed the limit. There’s no limit for buildings built after 2007 or buildings outside of rent-control restrictions. Depending on which part of Los Angeles someone lives, their building may or may not have local rent control in place.

Angelenos who need legal guidance on their living situation can reach out to Stay Housed L.A., a partnership between local governments and legal service providers. Tenants Together also provides a statewide Tenants’ Rights Hotline for counseling and information about tenants’ rights.

How we did it: We compiled monthly average rent data provided by Apartment List from across Los Angeles County.

Have questions about our data? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.