The Port of Los Angeles promised to measure pollution; its equipment keeps breaking

(Image generated with Mid-Journey)

The reporting was funded in part by the Southern California Center for Children’s Environmental Health Research Translation at the University of Southern California.

In the fall of 2021, the pandemic stretched, then briefly broke the global supply chain, causing everything from delayed Amazon deliveries to shutdowns of automobile plants. For weeks, more than 100 ships were stranded in the waters just off the Port of Los Angeles and the adjacent Port of Long Beach, waiting to unload their cargo. All the while, they were running their engines and pushing toxic exhaust into nearby areas, including Long Beach, Carson, Wilmington and San Pedro, home to roughly a million people.

For Long Beach resident Selena Zazueta, the period is etched on her lungs. “I don’t have asthma, but it felt like I did. It was hard to breathe and we were feeling headaches and nauseous every time we stepped out of our house,” she said. Air pollution from the ports is a fact of life for Zazueta, who is 42. Her second daughter was born with asthma; doctors told her it was due to air pollution.

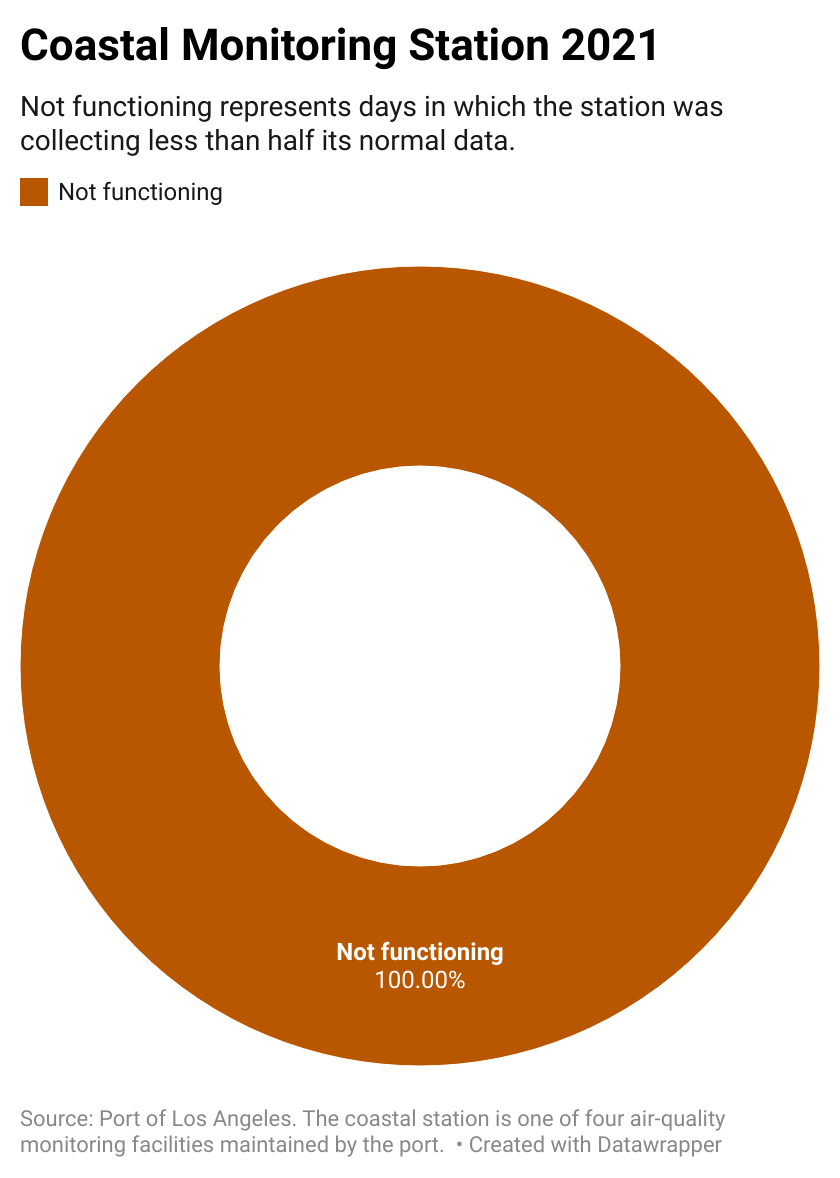

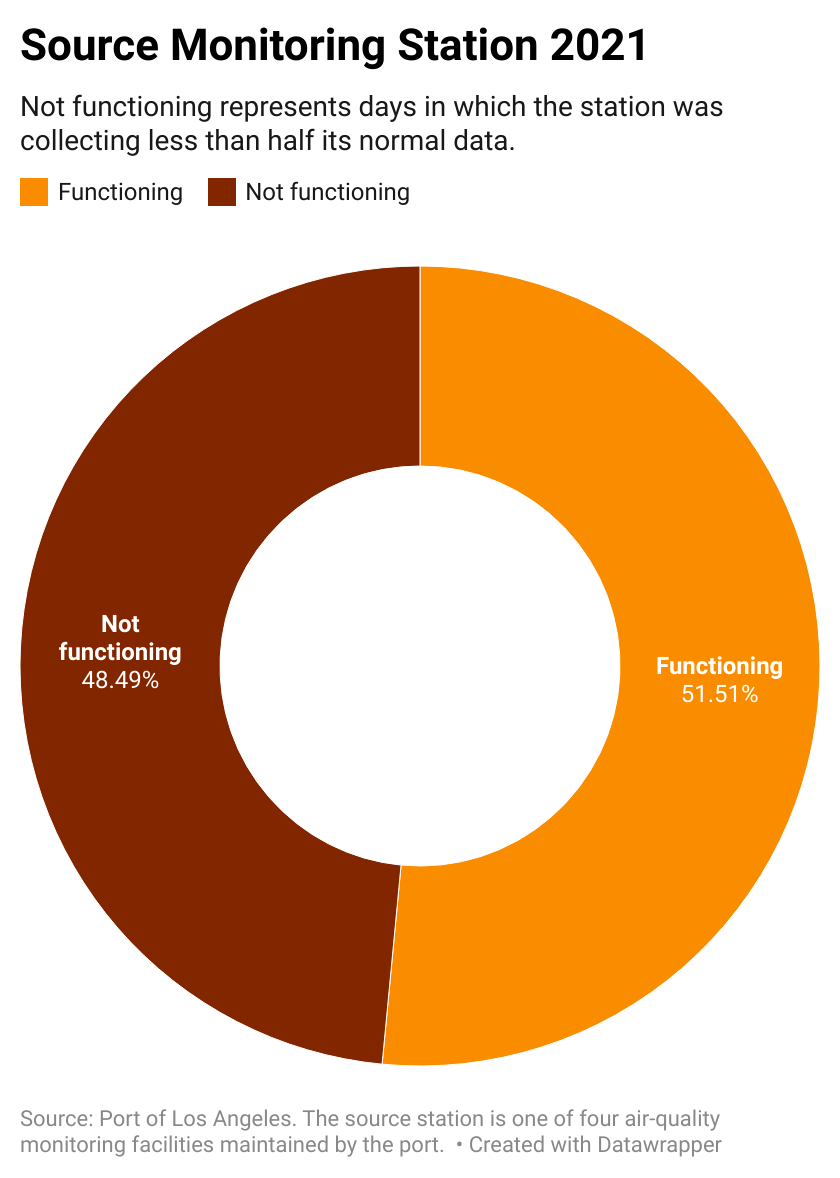

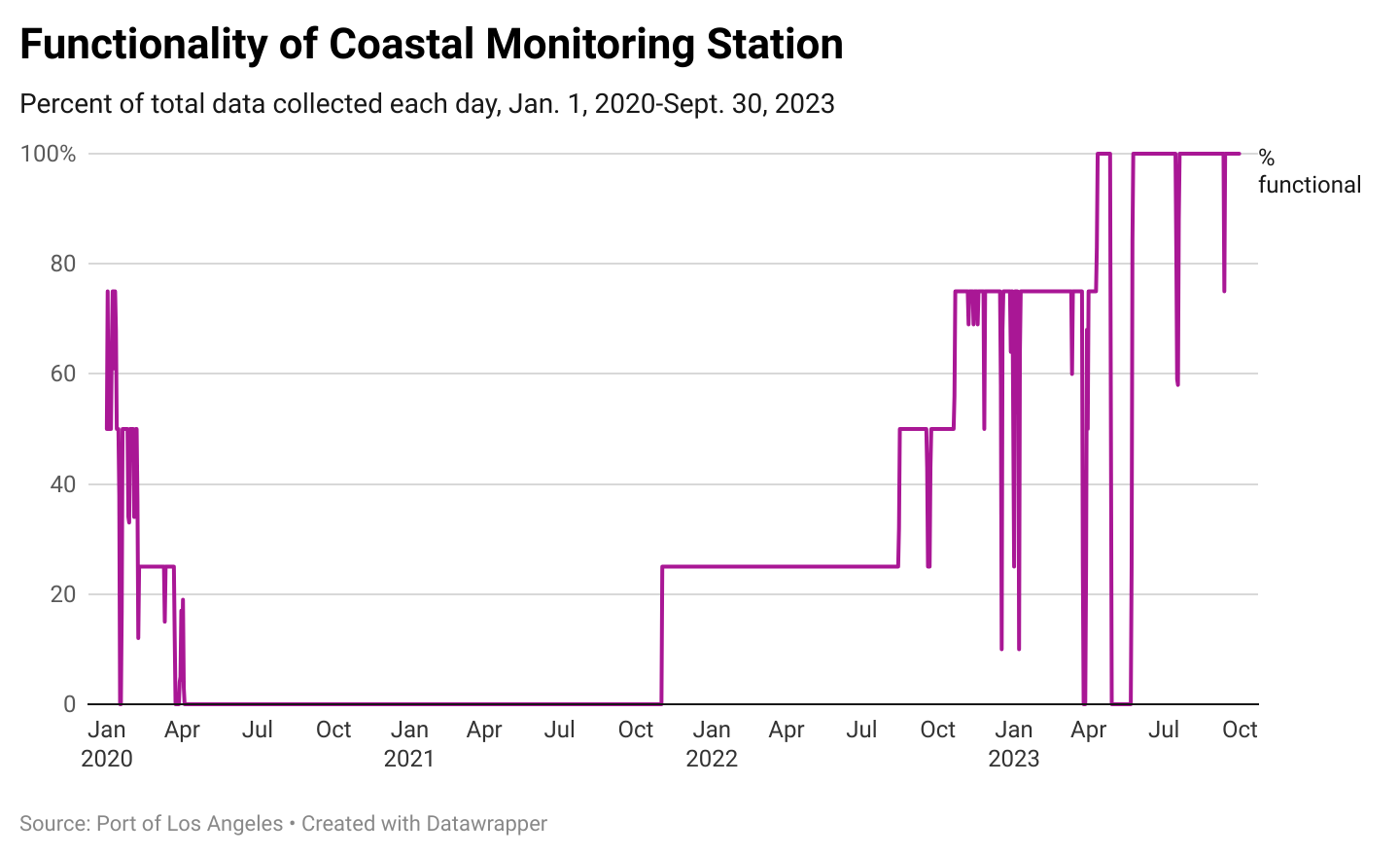

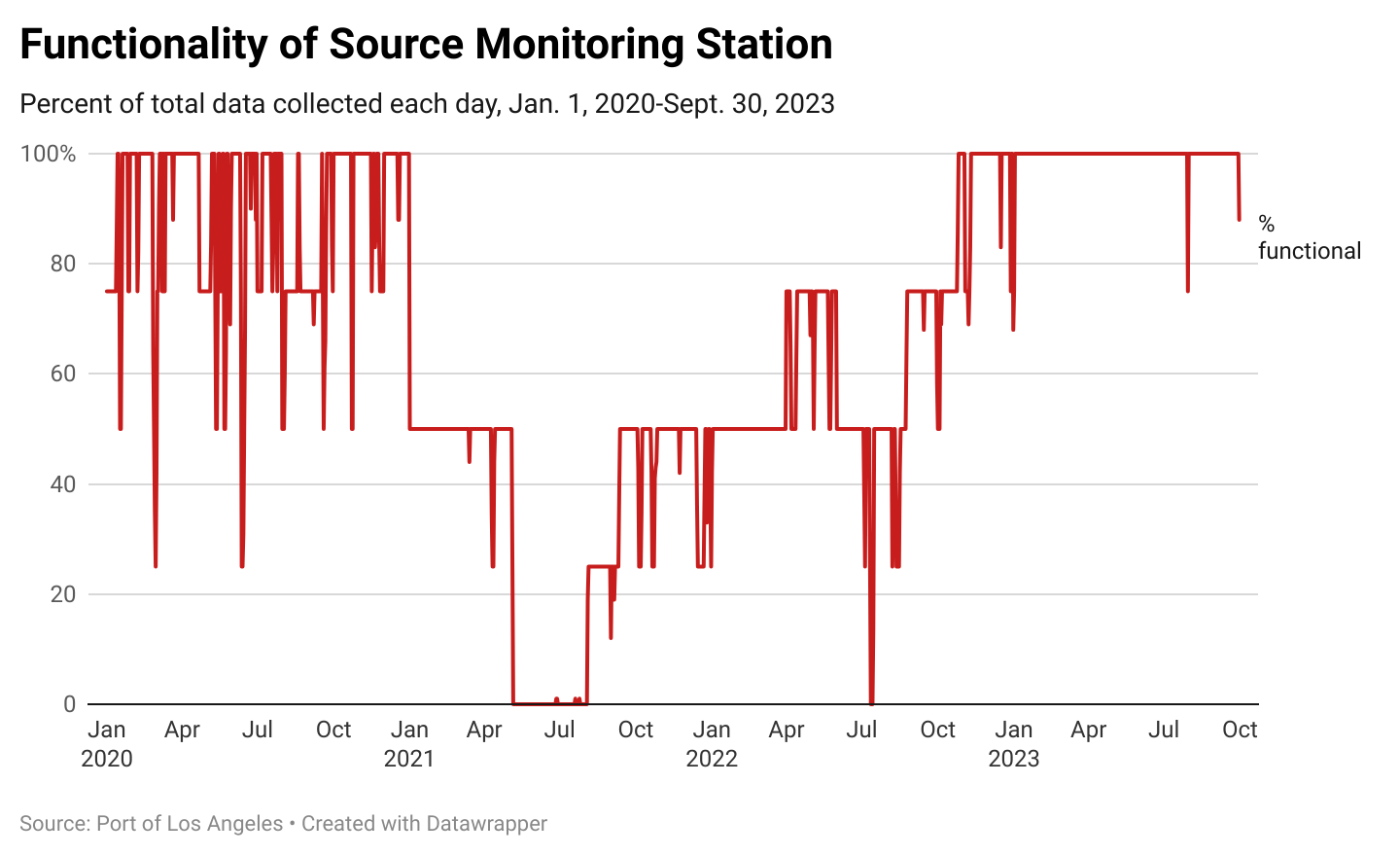

Exactly how bad the air quality was during that period is tricky to measure. That’s because half of the Port of Los Angeles’s air-quality monitoring stations weren’t working consistently. In fact, some of the air quality monitoring sensors were malfunctioning for nearly the entire year, according to an analysis of port data by Crosstown.

Accurate monitoring of the pollution from the ports is an urgent concern for the people who live nearby.

“Communities living on the frontlines of freight operations are disproportionately exposed to diesel exhaust from truck tailpipes, heavy equipment, ships, and locomotives,” said Heather Kryczka, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “As a result, these communities face elevated asthma rates, cancer risk and shortened life expectancy. This is a public health crisis – and it’s something that has been ongoing for decades.”

Multiple measurements

The port maintains four air-quality monitoring stations around its sprawling 7,500-acre operations–Wilmington, San Pedro, Coastal and Source. Other government agencies, such as the South Coast Air Quality Monitoring District, have their own stations nearby. Lisa Wunder, the port’s marine environmental manager, said there is “an unprecedented amount of air-monitoring in such a small area.” The failure of even several stations only mildly impacts the ability to monitor nearby pollution, she said.

Still, the malfunctioning of half of the port’s monitoring stations during one of the most intense periods of air pollution in recent years has enraged local community and environmental organizations. “The port has made commitments to mitigate pollution, transition to zero emission technologies, and enhance public transparency about its operations. But, to date, we’ve seen a pattern of the port delaying and falling through on its commitments,” said Kryczka.

The most common pollutant is fine particulate matter known as PM 2.5. These are tiny particles in the air that can go deep into the lungs. They have been linked to everything from increases in asthma to cardiovascular disease and dementia.

In 2021, sensors monitoring PM 2.5 were down every day of the year at the Port of Los Angeles’s Coastal station. The same station failed to capture ultra fine particle data, as well as ozone. Data for black carbon, a component of PM 2.5 that is a type of soot, was only captured 61 days that year. Another sensor was failing to collect even half of its data for 48% of the year during 2021.

The port’s San Pedro station fared better, and was collecting at least half of its data for 86% of the year in 2021. The station in Wilmington was fully operational that year.

Local residents say they have repeatedly raised the issue of the failing equipment with the Port of Los Angeles to no avail. Peter Warren, a member of the San Pedro and Peninsula Homeowners Coalition, in an email exchange with port officials, wrote that the lack of functioning air monitoring stations means, “there’s no cop on the beat.”

The densely populated areas near the ports in southwestern Los Angeles County – which also include Hawthorne, Lomita and Torrance – have been on the front lines of this environmental war for decades. These communities, with high populations of people of color, are surrounded by significant pollution sources: the nation’s busiest ports, oil refineries, rail yards and freeways crammed with diesel trucks.

Magali Sanchez-Hall, an environmental activist and longtime resident of the Wilmington neighborhood in Los Angeles, said she recognized numerous health issues in her community growing up.

“You get rashes,” she said. “You get allergies on your skin and don’t know why. Then you have headaches. Then all these strong smells. I didn’t know we had the worst air quality for every source of pollution you can imagine.”

The two-decade dispute

In 2003, the port, which is a department of the Los Angeles city government, settled a lawsuit initiated by the NRDC that alleged that the port was not complying with state and federal environmental regulations. Most of the $60 million settlement was allocated to a variety of air-pollution reduction projects to cut emissions from idling ships and trucks.

The Port of Los Angeles also initiated a program to monitor the concentration of a variety of pollutants in the air by setting up four stations at and around the area. The Port of Long Beach also began monitoring air quality.

But in recent years, local residents and environmental justice groups became increasingly alarmed by the spotty, or at times complete absence of data from the monitoring stations. In addition to the malfunctioning that occurred during 2021, several air quality sensors that monitor ultra fine particles at the port’s Coastal station were not working consistently last year, either. Monitors that measure PM 2.5 were only working 135 days of the year at the station. Black carbon at that station was the only data captured every day in 2022.

The problem has persisted this year. Between January and March of 2023 some of these sensors were non-operational 27% of the time at the Coastal station. Monitors that capture ultra fine particle data were not working during any of the first 90 days of the year. The other pollutants (black carbon, PM 2.5 and ozone) fared better, working 87 of the days.

Janet Gunter, part of the homeowners group that filed a California Environmental Quality Act lawsuit against the port in 2001, said that without fully functioning monitoring stations, there is no way to tell how much pollution she is breathing. “That puts everybody in a very bad place,” said Gunter. “They make promises they can’t keep and they tell half truths. It’s gone on for decades.”

Andrea Hricko, a professor emerita with the USC Keck School of Medicine, who has followed the pollution levels since 2016, says the absence of data also risks confusing people into thinking the air is clean when it’s not. “The instruments that they’re relying upon are not working, and it looks like they’re breathing clean air, but really it’s just that they’re not working,” she said.

Limited budget

The mitigation efforts the port has put in place, such as requiring most ships to cut their engines while in port, have led to improvements in environmental quality over the past decade. Still, the emissions generated by the cargo ships and trucks that move through the port, as well as the nearby oil refineries, result in heightened levels of air pollution, and during periods such as the supply-chain backlog of 2021, they can reach dangerous levels.

Joel Torcolini, a consultant with Leidos, a Virginia,-based firm that handles the port’s air-quality monitoring program, said the sensors are “notoriously difficult to operate,” and there are a variety of reasons why they haven’t been producing data on a consistent basis. In an interview, he explained that some of the problems are the result of bad cable connections, which led to data loss. Sometimes the sensitive wicks inside the sensors become saturated with water.

In recent public meetings the port has held on the issue, Torcolini said that there were delays in both the ordering and delivery of new equipment, with wait times as long as 20 months. Another port official said that on at least one occasion, the sensors had to be shut off because the air conditioning that keeps them cool was broken and it was taking their technicians several days to fix it.

These explanations have fueled a growing frustration among people who have been trying to hold the port to its air-quality obligations. In one meeting, Ed Avol, an expert in respiratory health and a retired professor at USC’s Keck School of Medicine, wondered why port officials were so slow to react once they detected a problem with one of the sensors.

“If you have a full-time tech monitoring the information on a daily basis, why wait a month to respond to what appears to be incorrect reporting data?” he asked.

Torcolini insists that, even with the gaps in air-quality data from the port, there is enough information from other stations, as well as those monitored by other government agencies, to establish a solid baseline of air quality in the area.

“So on a monthly average basis, if we don’t have these for just a month or two, in my opinion, it’s not negatively impacting it. I think we have it covered,” he said.

“My gut says, it might not be completely accurate, but I don’t have a reason to pull the data,” or not make it public, he said at a Port of Los Angeles meeting in May about the air-quality monitoring program.

Since the equipment fails frequently, Hricko, the professor emerita, asked why the port didn’t purchase backups.

Wunder, the port’s marine environmental manager, said that the port needs to spend its money wisely, and that purchasing back-up sensors would be costly.

“We don’t have an unlimited budget,” said Wunder. “If we spend all our money buying double of everything, we’re going to waste money on something that we could use to actually have a good impact on the program.”

The port spends roughly $500,000 on the operation and maintenance of its air-monitoring program, or roughly 0.25% of its annual operating budget. In addition, it has allocated $700,000 over an 18-month period to acquire new equipment at all four stations.

How we did it: We collected publicly available data from the Port of Los Angeles’s four air-quality monitoring stations beginning in 2020. We examined the hourly data to compile a model of when sensors were capturing their complete data for each day.

Have questions about our data? Or want to learn more? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.