Killing during catalytic converter theft shocks Los Angeles, but numbers are down

The murder last month of actor Johnny Wactor, who interrupted a group of men trying to steal the catalytic converter from his car, drew national attention. An investigation by Los Angeles Police Department Central Bureau homicide detectives into the shooting continues.

Yet the crime that led to the May 25 killing runs counter to recent trends. After spiking toward the end of 2022, catalytic converter thefts have dropped significantly.

“Our catalytic converter thefts for 2024 are 2,113 citywide,” LAPD Interim Chief Dominic Choi stated at the Los Angeles Police Commission meeting on June 4. At the same point last year, he added, there “were 3,857 thefts, which is essentially a 45.2% decrease citywide.”

[Get crime, housing and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

Heightened police attention and a collection of new laws targeting the buyers of stolen devices are believed to have contributed to the downturn.

Hunting precious metals

Wactor, 37, was best known for appearing on “General Hospital. He was working as a bartender in Downtown, and at around 3:25 a.m. he finished his shift and walked to Hope Street and Pico Boulevard, where his car was parked. As Wactor arrived, Choi said, he encountered three men, one of whom had used a floor jack to lift the vehicle.

“Wactor confronted the suspects and asked why they were doing this to his vehicle,” Choi stated. “After a brief verbal dispute one of the suspects produced a firearm and shot Wactor. All three suspects entered a vehicle and fled the location.”

Catalytic converters cut down on harmful emissions that vehicles produce. They are often targeted by thieves because they contain small amounts of precious metals which can be melted down (Toyota Priuses, which have higher amounts of the valuable metals, are frequently hit). A device can be cut away from a car in minutes, and can fetch several hundred dollars on the black market.

Vehicle owners can tell instantly that a converter has been stolen due to the loud, motorcycle-like rumble that sounds when a car starts. Replacing a device can cost thousands of dollars.

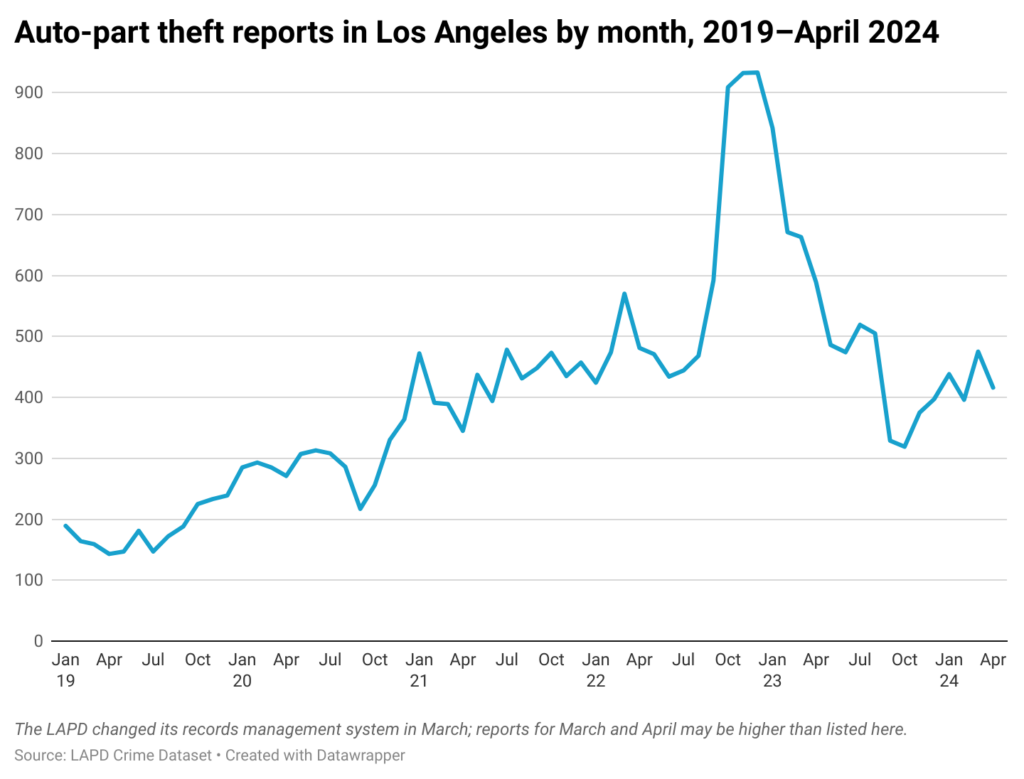

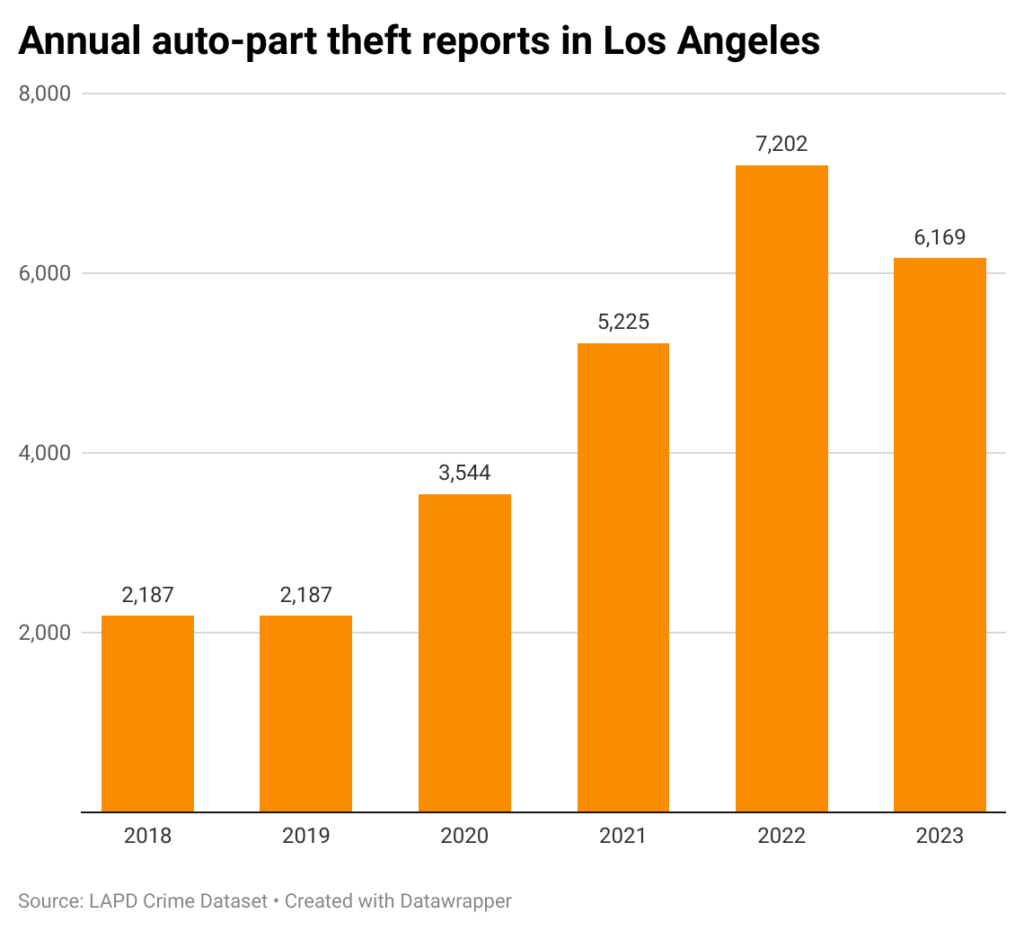

In 2018 and 2019 there were generally 150 to 200 monthly reports of auto-part theft, according to LAPD data (the count includes occasional airbags or headlights that can be resold). Numbers began rising early in the pandemic, then spiked in late 2022. From October through the following January there were approximately 900 auto-part thefts each month, according to publicly available LAPD data.

A flurry of news stories prompted law enforcement agencies to focus on the crimes. For much of the last year there have been in the vicinity of 350–500 reports each month.

Another reason for the decline is new state legislation that targets buyers of stolen devices. They are now required to have documentation showing that any purchased catalytic converter was not stolen or illegally removed.

The impact was seen in the 6,169 auto-part thefts tabulated by the LAPD in 2023. That represents a 14.3% drop from the previous year.

Targeting dense neighborhoods

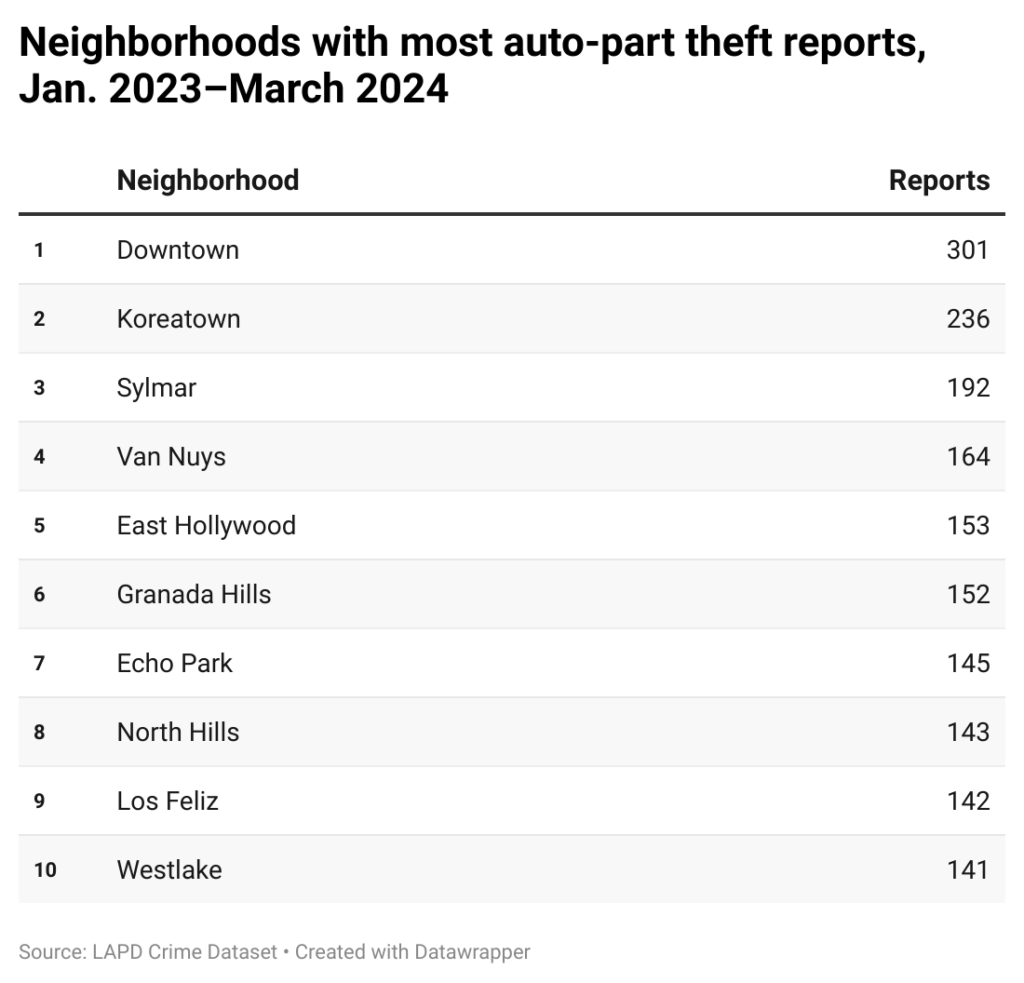

In March, the LAPD began instituting a new records management system that makes it difficult to break down which communities experience the most auto-part thefts. But in the past, unsurprisingly, the areas with the most traffic were hit hardest.

According to LAPD data, in the 15-month period from Jan. 1, 2023–March 31, 2024, Downtown recorded the highest number of auto-part theft reports, with 301. The next-highest count was the 236 incidents in Koreatown.

In a further effort to prevent catalytic converter thefts, the LAPD and other law enforcement agencies host occasional events in which a vehicle identification number can be etched on the device.

How we did it: We examined publicly available crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from Jan. 1, 2018–May 31, 2024. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Have questions about our data or want to know more? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.