Amid L.A.’s deep housing crisis, fewer apartments are being permitted

(See correction below)

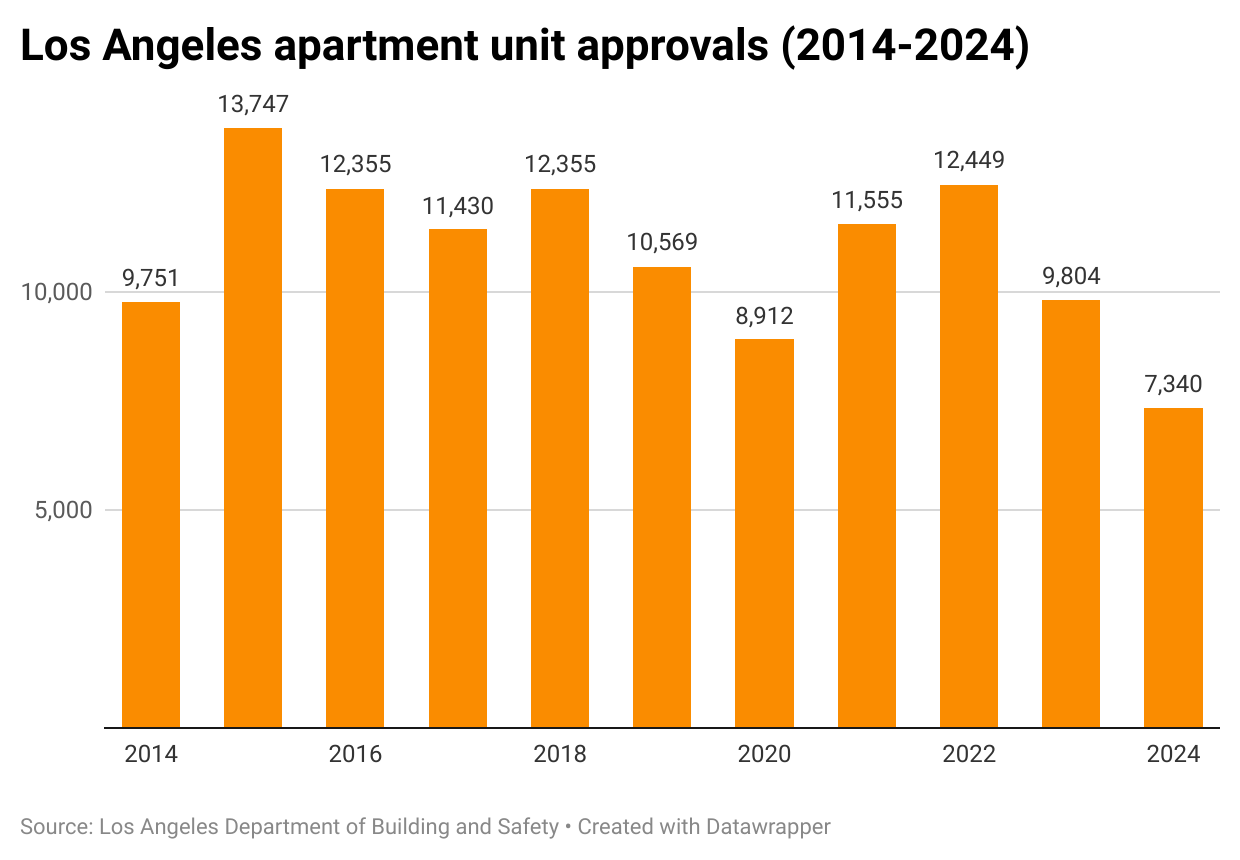

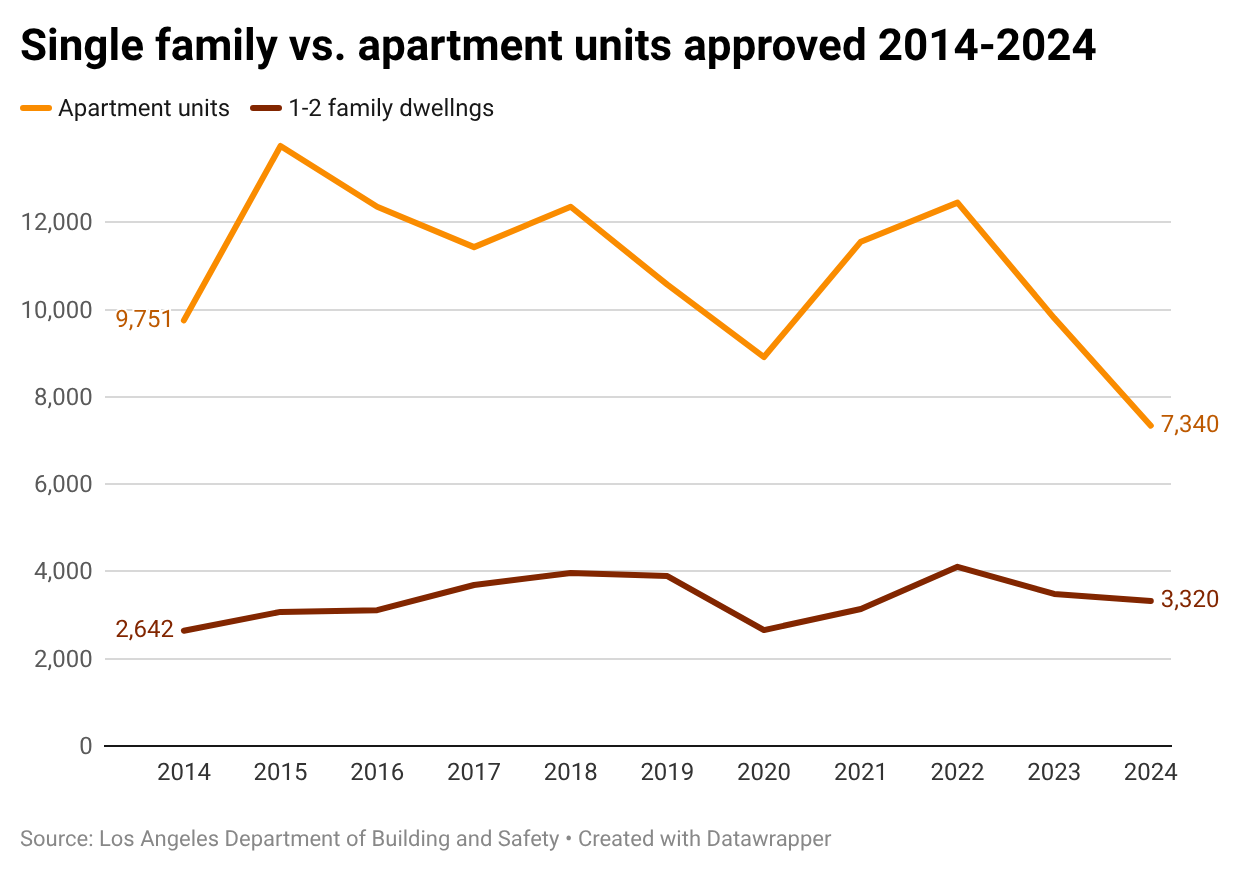

The number of apartment units approved by the city of Los Angeles last year was the lowest in over a decade, dropping 25% from the previous year and raising red flags for the city’s ability to generate anything close to the level of housing it says it needs.

Acquiring building permits is a major step toward creating new housing units. In 2024, 7,340 new apartment units were issued permits, according to data from the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety.

Housing supply is at the center of a slew of urban issues, including homelessness, housing affordability, quality of life and even traffic. By its own estimate, Los Angeles says it must add 456,643 units by 2029. Yet the creation of new housing has been in decline since 2014, and the drop has accelerated since 2023.

Behind the slowdown are a variety of factors, such as high borrowing costs, a stagnant supply of labor and restrictive zoning.

“It’s no surprise that most apartment developers have been sidelined or decided against new projects in L.A.,” said Nabil Awada, associate director for Matthews Real Estate Investment Services, based in El Segundo, Calif. “The higher all-in costs, along with the time it takes for permitting and approvals when dealing with [city agencies], make it extremely difficult for new development projects to pencil in.”

The construction of new single-family homes has also slowed in recent years. Last year, they accounted for 32% of all new permitted units.

This shift connects to the ongoing debate about density in Los Angeles. Housing advocates insist that the city must encourage more multifamily projects if it’s going to meet demand and address the lack of affordable housing.

Meanwhile, many neighborhood groups have resisted multifamily projects, arguing they would lead to parking and traffic snarls, and in other ways alter the character of their neighborhood. Currently, 72% of all land in the city zoned for residential projects is dedicated to single-family homes. Recently, the Los Angeles Planning Commission declined to expand the area where multifamily projects can be built.

Long-running efforts

The housing shortage did not appear suddenly, and city officials have long sought to address the issue. That includes Mayor Karen Bass, who, days after taking office, issued an executive directive to fast track low-income and homeless housing projects. Her office has said that approvals that once took more than six months can now be granted in under two months.

Then there is Measure ULA, also known as the “mansion tax,” which was approved by voters and went into effect in 2023. It imposes a 4% tax on the sale of properties over $5 million, and an even higher levy on projects above $10 million. The proceeds are intended to fund affordable housing and anti-homelessness efforts. According to a ULA dashboard, more than $479 million has been generated through 713 transactions.

However, the measure does not distinguish between luxury properties and multifamily housing. Mott Smith, chairman of the board of the Council of Infill Builders, argues that it is one of the contributors to the slowdown in new apartment projects.

“It really makes it the case that you’re penalized for adding value to projects at an exponential rate, so it harms people who are building a lot more than it harms people who are just buying the status quo, and keeping the status quo,” Smith said.

Indeed, Measure ULA had been touted to generate as much as $900 million a year.

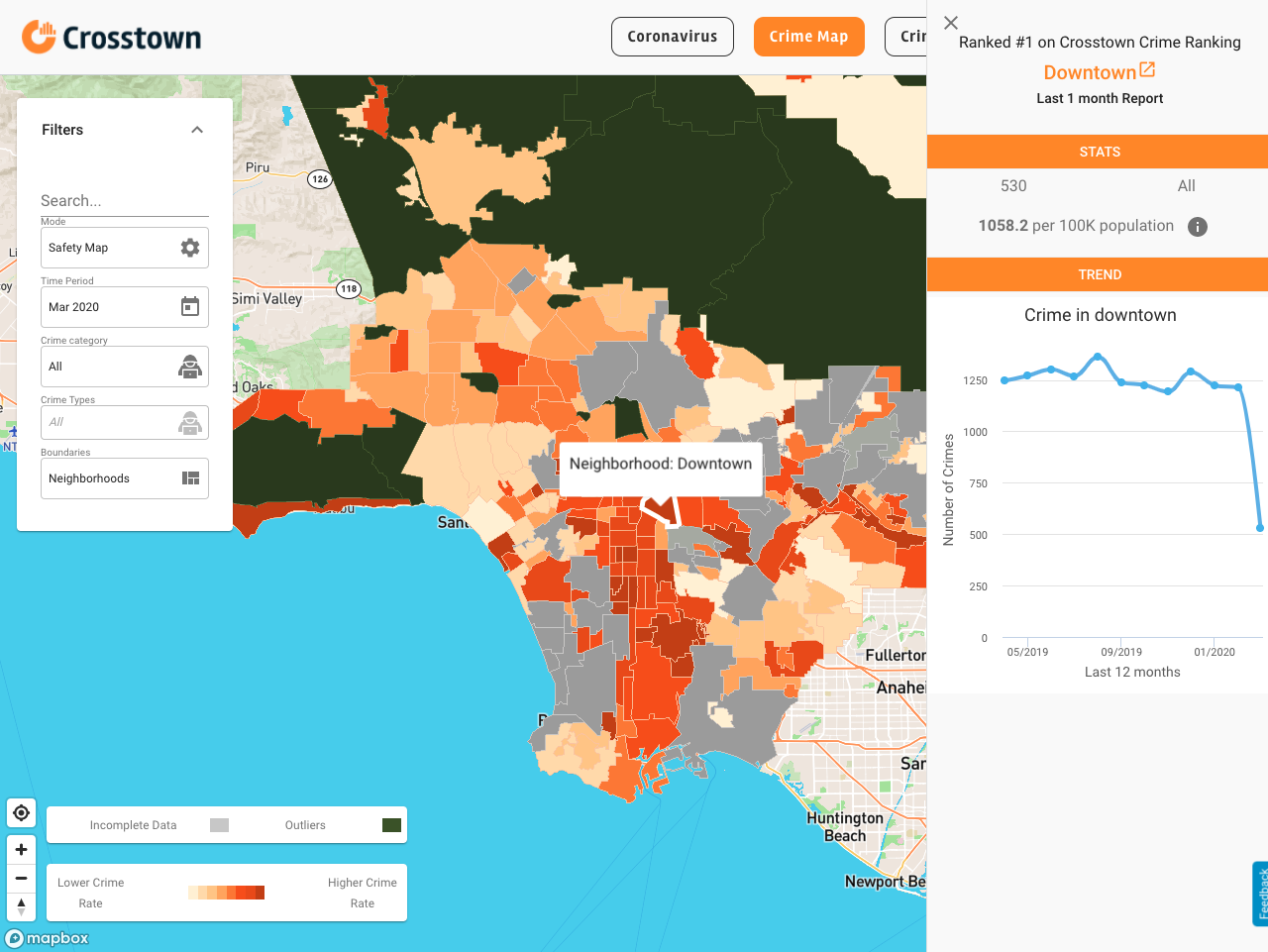

DTLA Slowdown

Ten years ago, Downtown Los Angeles was home to roughly one-quarter of all of the apartment units approved by the Department of Building and Safety, with 4,856. Last year, it produced only 477, or 6.5% of that total.

But much has changed in the neighborhood in that time. The pandemic, and the spread of tent encampments, prompted many residents to leave the area. The rise of remote work also diminished the number of office workers in Downtown. Those factors, along with higher interest rates, have made housing developers cautious about moving forward with projects that can cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars.

Still, efforts are underway to build upon Downtown’s current stable of 47,000 residential units, according to a 2023 report from the Downtown Center Business Improvement District. The City Council last year adopted the Downtown Community Plan, along with a new zoning code that doubled the area where housing is permitted. The hope is to add 100,000 units to the neighborhood by the year 2040.

Citywide, the post-pandemic building boom is now screeching to a halt, according to Rob Warnock, senior associate at the rental platform Apartment List. “The period of high growth, large supply, large construction activity that we’re in right now is definitely slowing down.”

Hilgard Analytics, a real estate and economic research firm, noted that the current slowdown could be traced to factors such as higher borrowing costs, as well as labor disputes. Hilgard predicts that the chronic shortage of housing will eventually lead to a resurgence in building.

While Los Angeles’s supply of new housing has been decreasing on and off for a decade, at the national level, the number of permitted housing units has been increasing, except in 2023, which saw a slight dip, according to the U.S. Census Bureau data.

Correction: Much of the data in this article has been updated since it was initially published on Dec. 4, 2024. Due to an editing error, the initial methodology used to calculate apartment unit approvals excluded one category of data, resulting in lower numbers. That has been corrected, resulting in higher annual totals. In addition, this article has been updated with full year data from 2024 and was updated again in July 2025.

How we did it: We examined publicly available permit data for new residential construction from the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety for the previous 11 years.

Have questions about our data or want to know more? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.