‘Modern-day slavery’ in Los Angeles

It was 5 a.m. on June 6 of this year when an 18-year-old Hispanic female involved in commercial sex acts was attacked at a motel on the 9600 block of S. San Pedro St. in the Broadway-Manchester neighborhood. The suspect pulled her hair, choked her, then knocked her to the ground. The suspect threatened to kill her.

At 12:01 a.m. on New Year’s Day, Jan. 1, a 16-year-old white female was working as a prostitute when she was overwhelmed by multiple suspects at the intersection of Zombar Ave. and Valerio St. in Van Nuys.

Both of these girls were victims of human trafficking, according to publicly available LAPD data.

Human trafficking, a form of “modern slavery,” is the “business of stealing freedom for profit,” according to the National Human Trafficking Hotline. U.S. law defines human trafficking as the “use of force, fraud or coercion to compel a person into commercial sex acts, labor or services against their will.”

In California earlier this year, nearly 50 victims of trafficking, including 14 minors, were rescued during a three-day sting operation across the state that led to 339 arrests.

While popular culture would have us believe that human trafficking means underaged women locked in the back of an 18-wheeler being transported across the country, sometimes it can mean forcing someone to work for unfair wages or trapping someone here by taking away their passport so they are unable to leave the country.

Human trafficking is categorized by the LAPD in four ways: commercial sex acts, involuntary servitude, pimping and pandering, according to Det. Lina Teague, the officer in charge of human trafficking for the department.

Det. Teague said involuntary servitude crimes include labor cases, such as not paying a nanny, or cases involving immigrants being exploited for their work. Pimping cases involve earnings received from prostitution. Pandering is when someone takes possession of another person for prostitution.

“Sometimes guys will go out on the street and tell the girls ‘you shouldn’t be out here alone, you should be working for me,’” said Det. Teague, regarding pandering.

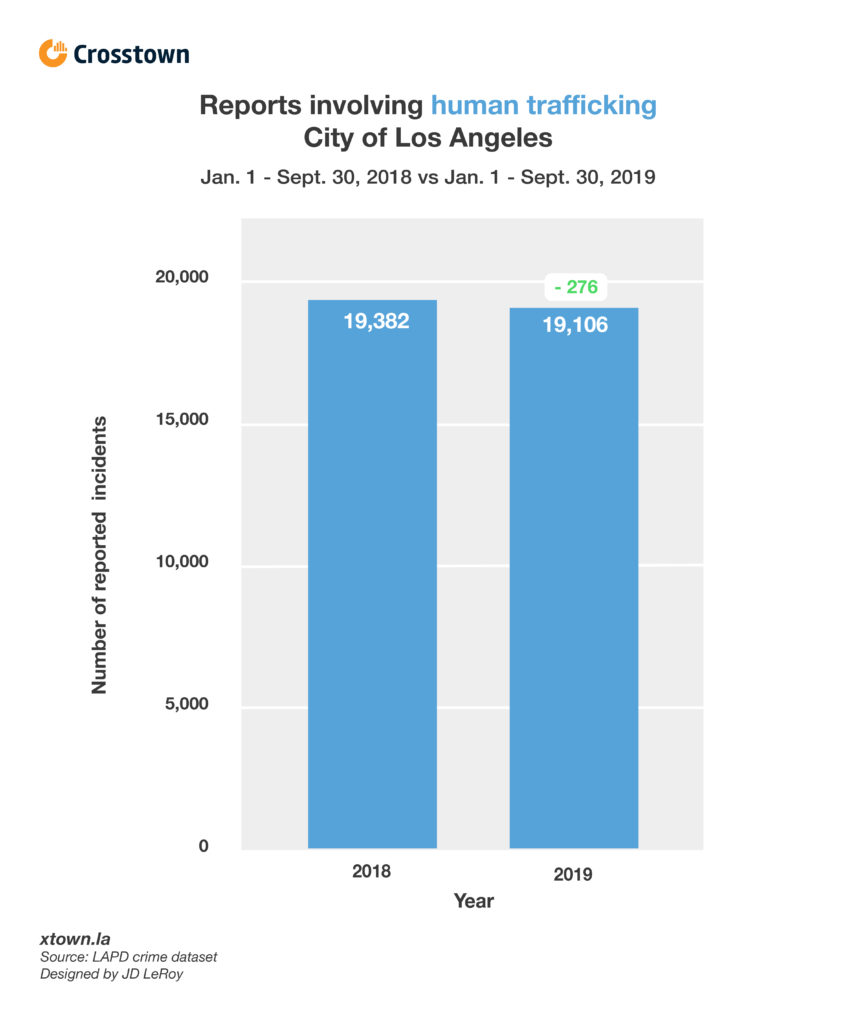

Here in the City of Los Angeles, reports of human trafficking are down 1.4% for the first nine months of 2019 compared to the same time last year.

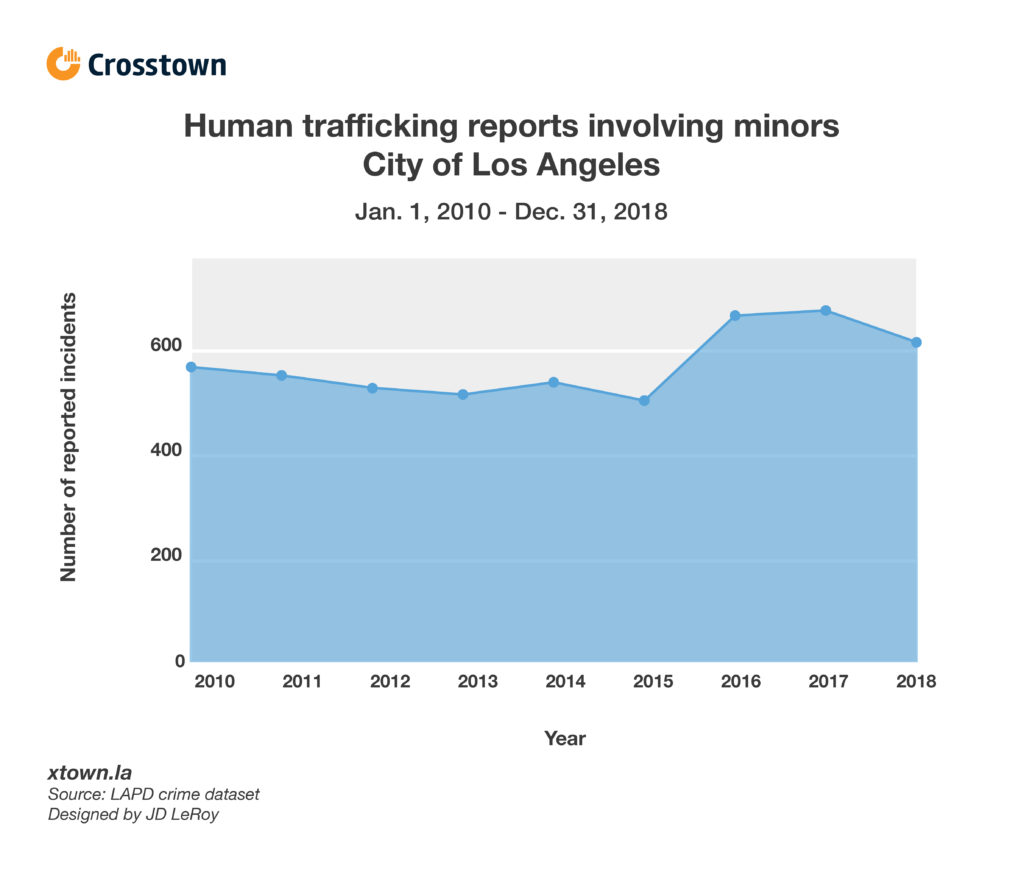

Between Jan. 1, 2010 (when the LAPD first made its data publicly available) and Dec. 31, 2018 (the most recent complete year of data), there were 174,827 reported cases involving human trafficking in the City of Los Angeles. In nearly 3% of these cases, children 17 and under were the victims.

These are, of course, only the cases that are reported. The Human Trafficking Hotline reports that as shocking as these numbers are, they are likely a tiny fraction of the actual problem.

If you’re thinking it could never happen in your backyard, think again.

Publicly available data reveal the Vermont Square, Van Nuys and Florence neighborhoods rank highest in overall human trafficking from Jan. 1, 2010 – Dec. 31, 2018. Hyde Park and Vermont-Slauson round out the top five.

Downtown, Sawtelle and Westlake had the highest number of reported cases of human trafficking for the first nine months of this year, with all three seeing staggering increases of 160%, 60% and 42.8%, respectively from the same period last year.

Los Angeles’s many diverse communities make it easier for traffickers to hide victims and move them from place to place, according to research conducted by the Pacific Council on International Policy. Indeed, Los Angeles County was identified as a major hub for the commercial sexual exploitation of children in 2012. Advocacy organizations say undocumented immigrants are particularly vulnerable to falling prey to human trafficking.

Need help? Resources:

- Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking

- The Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA)

- Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project

How we did it: We examined LAPD publicly available data on reports of human trafficking involving commercial sex acts, involuntary servitude, pimping and pandering the first nine months of 2019 compared to the same time period last year. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here. LAPD data only reflect crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. On occasion, LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.