As youth arrests dwindle, racial disparities widen

The Los Angeles Police Department has made major strides in reducing the number of juveniles it arrests. But even as the numbers have fallen, dropping 87% over the last decade, racial disparities have widened.

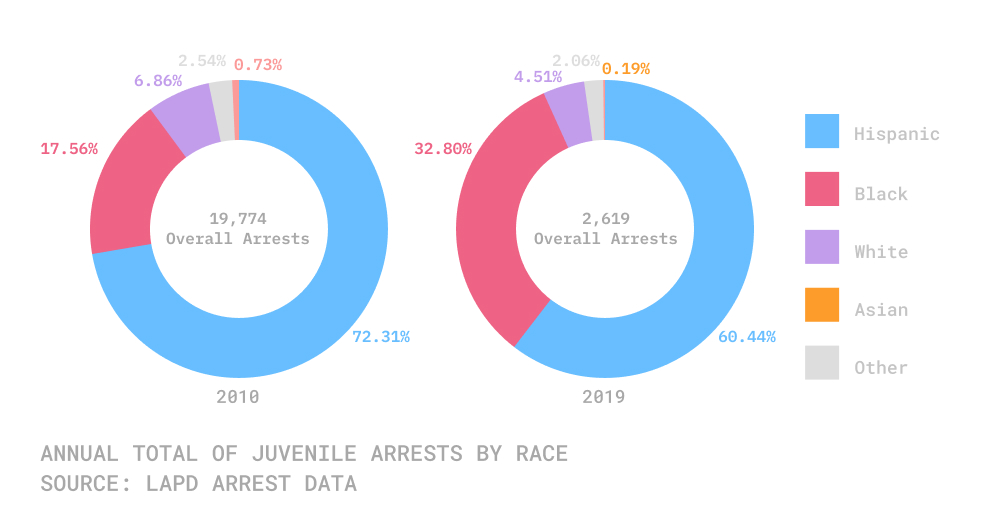

In 2010, the LAPD arrested 19,774 kids; 18% were Black.

Last year, they arrested 2,619, but the percentage of Black kids nearly doubled, to 33%. Black people make up 9% of the population in the City of Los Angeles.

By comparison, white kids accounted for less than 5% of total juvenile arrests in 2019; 29% of the city’s population is white. Hispanic kids represented 60% of total arrests; 49% of city residents are Hispanic.

As the LAPD makes fewer juvenile arrests, a larger percentage of them are Black

A trend amplified in kids

The shift is an illustration of how even an apparent success –– such as cutting back on the number of juveniles arrested –– still fails to address the racism embedded within the justice system, especially when it comes to kids.

Yearly LAPD youth arrests by race

The racial disparities in juvenile arrests, which includes kids aged 13 to 17, are even greater than they are for adults. Black adults made up 28.4% of all LAPD arrests in 2019.

“These disparities persist throughout the various stages of justice system contact,” said Dominique Nong, the director of youth justice policy at the Children’s Defense Fund-California.

She noted that the skewed arrest data is amplified even more as Black kids move through the system. Black youth are five times more likely to be detained than white youth, and are more likely to be tried as adults for the same offenses.

Across the nation, the number of youth arrests spiked in the ’80s and ’90s, when it was considered a major strategy for crime suppression. Many states, including California, passed a series of measures that increased punishment for youth offenders. By catching young criminals and even sentencing them to long periods of detention, the logic went, authorities would be reducing the potential for crime in the future.

But the opposite happened. Arresting someone at an early age only increased their chances of being arrested again. Once they were in the criminal justice system, it was hard to exit.

“When juveniles are arrested, it significantly decreases the positive outcomes of their life across a variety of different measures,” said Charlene Taylor, a senior researcher at the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. “Whether we’re looking at educational attainment, employment, average income as an adult, future of substance abuse … there are so many things.”

Rolling back a punitive approach

More recently, California began to move away from the punitive approach. In 2010, then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed a bill decriminalizing possession of small amounts of marijuana. In the following year, possession-related arrests for juveniles in California fell by 61%, according to a report by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

In 2014, the Los Angeles United School District reformed its policies to focus on counseling and other school resources instead of issuing citations to students for fights and disciplinary infractions. Copious research has shown how approaches such as suspending students from school for behavior is more likely to push them into the criminal justice system.

As the data indicates, the LAPD stopped focusing on arresting juveniles to curb crime a decade ago.

“What we found in juvenile justice is that law enforcement oftentimes only made matters worse, not through any fault of law enforcement, but the criminal justice system, the harshness of it, the bracing nature of it, did not encourage necessarily recovery or redemption,” LAPD Chief Michel Moore said at a press conference in January.

Yet even a dramatic cutback in the number of arrests was not enough, as the improvements ended up magnifying the racial inequalities further.

“If [the decision to arrest] is made even in part based on that child’s race, I think it has more of a collective or cumulative effect when we start to look at the impact on Black communities,” said Taylor, who consults with juvenile corrections agencies as part of her work with the National Council on Crime and Delinquency.

On June 3, the City Council introduced a motion to reinvest the $100-150 million in cuts from the LAPD into disadvantaged communities and communities of color.

How we did it: We examined publicly available LAPD arrest data from 2010 to 2019. Learn more about our data here.

Want to know how your neighborhood is faring? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.