After pot was legalized, more Black people were arrested

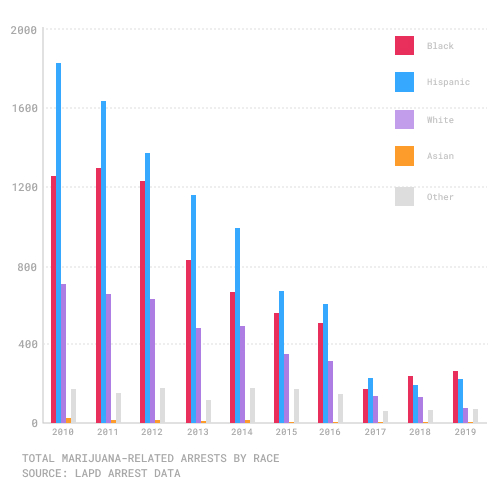

In 2017, when recreational cannabis was still illegal in California, the Los Angeles Police Department arrested 173 Black people for marijuana-related offenses. The next year, cannabis was legalized, and the LAPD arrested 239 Black people for those offenses. Last year, the number jumped again, to 261.

The climbing numbers of arrests for Black people point to a chronic failure in the way marijuana legalization has played out across Los Angeles.

In 2016, voters in California passed Prop. 64, which made recreational cannabis use legal. It went into effect on Jan. 1, 2018. The measure drew broad support, particularly from civil rights groups, which noted that Black and Latino communities had endured disproportionately higher arrest rates and stiffer sentences under drug laws. Advocates thought the new law would reverse this troubling trend.

But in the two and a half years since marijuana use was legalized, the opposite has happened. Though overall arrests for marijuana-related offenses have fallen sharply over the past decade, Black people now make up a larger percentage of those being detained.

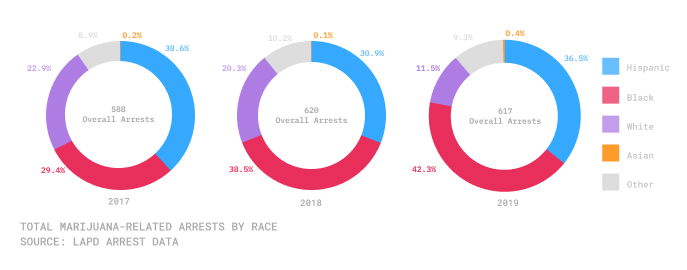

In 2016, Black people accounted for 32.2% of all marijuana arrests in Los Angeles. Last year, that portion rose to 42.3%, according to LAPD data. Black people make up 8.9% of the city’s population.

White people, meanwhile, accounted for 20% of all marijuana arrests in 2016. Last year, they accounted for only 11.5%. Non-Hispanic white people are roughly 28.5% of the city’s population.

Post-legalization, more Black people arrested for marijuana

Graphics by Kiera Smith

“Marijuana legalization can dramatically reduce arrests overall, including the numbers of arrests of people of color, but it can’t alone undo racially biased policing and the much larger issue of how and why we over and unfairly police some communities,” said Tamar Todd, a civil rights lawyer who serves on the California Cannabis Advisory Committee. “And I think these numbers reflect that large problem.”

According to Todd, the increase in racial disparities in California as well as other states, such as such as Maine and Massachusetts, has happened because, “We devote more police resources toward controlling and over-policing Black communities and that will tragically be reflected in more arrests for every category of offense than in communities. …with little police presence,” she said.

Marijuana enforcement has historically targeted Black and Latino people disproportionately, according to a study from the UC Davis Law Review. The findings show that from 2006 – 2008, Black people were arrested for marijuana possession at rates up to twelve times the white rate in 25 California cities. It was seven times greater in Los Angeles. That same study found that from 2004 – 2008, Black people in all of California’s largest counties were arrested for marijuana possession at “double, triple, even quadruple” the rates of white people.

Black people now account for the largest percentage of marijuana arrests

Legalization was supposed to change that. Making possession of up to an ounce no longer a crime was expected to dramatically reduce the burden on Black and Latino communities.

In fact, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Drug Policy Alliance all supported Prop. 64, claiming it would reduce mass incarceration for people of color and help correct uneven sentencing guidelines resulting from drug policies, according to reporting by Cal Matters.

At a press conference earlier this month, Gov. Gavin Newsom said that marijuana legalization was a civil rights issue and that he was proud California led the way to address racial disparities in the criminal justice system and the “ills of the war on drugs.”

Unequal access

Yet in Los Angeles, the disparities have only widened. One of the potential reasons is that those same Black and Latino communities have had lower levels of access to legal marijuana in the city.

Wealthier and predominantly white areas, such as Studio City, North Hollywood, Fairfax and Westwood are home to dozens of dispensaries. Meanwhile, the entire south part of Los Angeles, including areas with larger Black populations, such as Hyde Park and Watts, has fewer than 10 dispensaries registered with the city.

Critics charge that the city’s process for granting licenses for marijuana dispensaries did not offer adequate opportunities to businesses in areas that had borne the brunt of repressive drug policies. The city’s Department of Cannabis Regulation announced a social-equity program last summer that would help applicants applying for ownership opportunities in the marijuana industry “in order to decrease disparities in life outcomes for marginalized communities and to address the disproportionate impacts of the War on Drugs.”

The Los Angeles City Council is also changing the criteria for people who qualify for the program to make sure that those hardest hit by unequal drug policies are able to benefit, since Black cannabis entrepreneurs are underrepresented. The city is also changing the rules about when cannabis companies can open in neighborhoods that already hit limits on the number of dispensaries.

“Legalization creates legal access, but that access can be unequal,” said Todd. “Those with the means to access limited legal supply, transport to a legal source, and private residence where they can legally consume reflect larger race and wealth disparities in society beyond marijuana.”

Calls for a new approach to policing

A study by the ACLU covering 2010-2018 also found that Black people in California were significantly more likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana-related offenses. The same ACLU study calls for the police to figure out new ways to measure productivity instead of using metrics like the number of stops or citations and for states to reallocate resources for things like public health and community-based services. The People’s Budget LA is also calling for similar reform in the way Angelenos tax dollars are spent.

Last month, the NAACP sent a proposal titled “Black Community Wellness” to LAPD Chief Michel Moore and Mayor Eric Garcetti that recommends a number of programs the city should implement to increase diversity and inclusion, said Ron Hasson, who serves as chair of the California-Hawaii State Conference Branch Development committee for the NAACP.

“We are interested in having conversations with the LAPD to get more insight as to why the [arrest] numbers are going up for African Americans,” said Hasson. “Is it a result of racial profiling? It’s important that we understand how this law is affecting our community.”

A vast majority of the arrests in the City of Los Angeles are listed as “possess marijuana for sale” or “transport/sell/furnish/etc.” marijuana with intent to sell. Of the 411 arrests this year through June 22 (the most recent period for which data is available), only 20 received an infraction for smoking marijuana in public.

A detective at the 77th St. Station, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said they have to see someone selling marijuana or see there was evidence the marijuana was for something other than personal use. That evidence would include things such as baggies or scales, the detective said.

Nick Stewart-Oaten, an attorney with the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s office, said in possession-for-sale cases, it is unusual for a police report to claim that an officer actually caught someone selling marijuana illegally. Stewart-Oaten added that, far more frequently, the police decide the defendant was selling marijuana based on elements the officer observed during a stop or search, including large amounts of marijuana, baggies or other evidence.

The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office did not provide comment to a written set of questions.

“The problem is that many of the things that suggest a defendant was selling marijuana can be interpreted multiple ways and are not necessarily proof that the defendant was selling,” said Stewart-Oaten. “For example, the fact that the defendant had a lot of marijuana could mean the defendant was selling, but it could also just mean the defendant likes weed.”

How we did it: We examined LAPD marijuana arrest data from Jan. 1, 2016 – June 22, 2020.

Interested in our data or have additional questions? Email us at askus@xtown.la.