Is coronavirus masking domestic violence?

Police in Los Angeles responded to fewer calls for domestic violence in the past four months compared with the same period last year. But rather than applaud the decrease, experts worry that a side effect of the coronavirus lockdown is that victims lack opportunities to report their abusers.

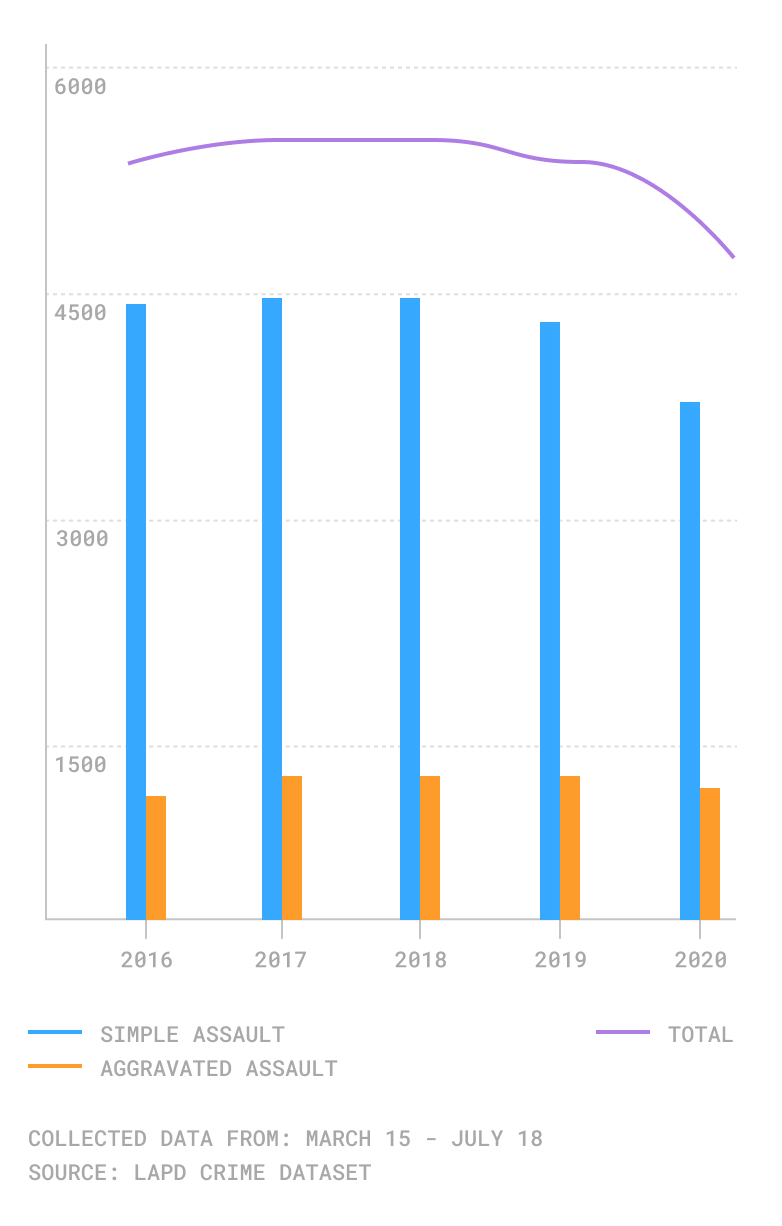

A Crosstown analysis of LAPD data found that 4,655 domestic violence incidents were reported from March 15, when stay-at-home-orders began to be put in place, and July 18 this year, a 12.5% drop from the 5,324 reports filed in the same time period in 2019. The department also received 14,086 calls for service related to domestic violence in the recent four-month period, which is about 700 fewer than the previous year. Service calls are a record of all instances in which the LAPD responds, including calls that come through 911, calls to non-emergency numbers and incidents officers observe while in the field.

The 4,655 domestic violence reports since Mayor Eric Garcetti ordered widespread closures and instituted the Safer-at-Home order (it was relaxed two months later) is also lower than the roughly 5,300-5,500 incidents recorded over a comparable four-month period every year going back to 2016.

Aggravated and simple assault by a domestic partner

Graphic by Kiera Smith

Angelenos are still being urged to stay indoors as often as possible, and Garcetti has stated that a second stay-at-home order could be enacted if coronavirus infections continue to rise. That could pose a problem for victims, as Det. Marie Sadanaga, the domestic violence coordinator for the LAPD, said that already nearly 19% of the time police responded to a domestic violence service call, no one was there.

She termed that scenario, “gone on arrival.”

Ruth Glenn, chief executive of The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, a non-profit dedicated to supporting survivors and holding offenders accountable, told Crosstown in April that the number of service calls was alarming but not surprising, and cited a need to increase outreach to potential victims.

Few incidents reported

Many domestic violence incidents are unreported. Sadanaga said sometimes this can be attributed to differences across various ethnic backgrounds, and that some victims don’t recognize domestic violence as violence because it is so ingrained in their culture. She added that many undocumented individuals fail to report domestic violence for fear that contacting police will put them at risk of deportation.

“There’s also a misnomer that all victims even call the police,” said Glenn. “They may end up going into shelters and never call the police.”

The bulk of domestic violence victims in the past four months were people of color, with Black and Hispanic people making up 76% of the 4,655 incidents reported to the LAPD. Hispanic victims reported 2,299 incidents of domestic violence during the lockdown, a drop from the 2,627 reports during the same period last year. Black people reported 1,240 domestic violence incidents during that time, a 15.5% drop from 2019. The proximity of victims to their abusers during the shutdown, and the potential difficulties in alerting authorities, has experts worried that the true figures are far worse.

“We are working on addressing this issue,” said Sadanaga. “ We are talking to the right people in the community to find solutions to these problems.”

Glenn said her organization is also trying to see how to best serve people of color, particularly Black men and women who are marginalized by systems that are intended to help them.

“I’m a strong believer that advocates do all they can, but we need to look at when we have too many Black women survivors saying they can’t get what they need,” Glenn said.

Dr. Angela Parker, director of training for The Jenesse Center, a South LA non-profit that specializes in domestic violence and providing families with services such as vocational classes, mental health and legal services, said in a video posted to YouTube that the majority of their clients are children. “We understood early on that children were equal victims of domestic violence. We do a lot of prevention work with youth so they are educated on how to recognize toxic relationships,” she said.

Possible solutions

One solution could be expanding the Domestic Abuse Response Team, or DART, program, said Sadanaga. DART is a multidisciplinary crisis response team that pairs domestic violence victim advocates with specially trained officers. She praised the LAPD effort’s effectiveness, but noted that currently there is only one DART unit for each police division, and it runs four days a week for 10-hour shifts.

“In a perfect world, the program would run seven days a week, 24 hours a day,” she said.

Sadanaga recalled how a phone call she heard during a training session almost four years ago helped inform her of the reality faced by victims. She detailed the frantic 911 call of a small boy, around five-years-old, who called in because his father was beating his mother. Sadanaga said the boy was crying uncontrollably while hiding in a closet. She recalled listening to dispatchers try to get him to remain calm and to assure him help was coming.

“It was heart-wrenching,” she said.

Glenn said every survivor needs something different, and it is not possible to know what a victim requires until help arrives.

“I can’t tell you how many times victims will say I don’t want the police and I don’t know why the neighbors called,” she said. “It’s not an equally answered question.”

When asked about calls by activists to defund the police, Sadanaga said the DART program is funded by the Mayor’s office, so no money would be taken from the program if the department’s budget is cut. She admitted there are differences in opinion within the LAPD about whether social workers could replace LAPD officers on certain calls, but said domestic violence calls are some of the most dangerous ones that police answer.

“Having a trained advocate working on behalf of victims can stop the cycle of abuse because their sole purpose is figuring out what a victim needs to feel safe,” she said.

Future help could come from a change in state law. On July 30, the state Assembly will discuss SB 1141, a bill sponsored by Sen. Susan Rubio (D-Baldwin Park) that would criminalize intimidation and threats meant to frighten victims. It passed unanimously in the Senate in June and would expand legal protections for survivors of domestic violence. It is sponsored by the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office and has the support of many domestic violence advocates.

“An abuser uses physical violence and ‘coercive control’ behavior to dominate the abused. For all the survivors out there, we are listening, we hear you, and we remain committed to preventing and ending domestic violence,” Rubio said in a prepared statement.

But what happens after laws are passed, police are involved and courts step in? Sadanaga said this is where safety planning comes into play, which involves figuring out if the victim can stay with family or emergency shelters and be notified when the abuser is released from jail.

Glenn stressed that people need to be able to seek the help they need, even in uncertain times.

“We want to reassure survivors across the nation to not let the pandemic stop you from reaching out for help,” said Glenn. “The pandemic shouldn’t let you live more in fear.”

How we did it: We examined publicly available LAPD data on reported crimes in the City of Los Angeles. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available.

The LAPD periodically updates past crime reports with new information, leading the department to recategorize past reports. Additionally, revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database. But, we will keep monitoring hate crimes in the City of Los Angeles.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.