Street vendors risk a lot to make a living

Angelenos are increasingly returning to work, and are adopting strict new safety protocols, including masks and social distancing. Street vendors are also resuming their jobs, but are finding that, in some ways, the work is just as dangerous as it was before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

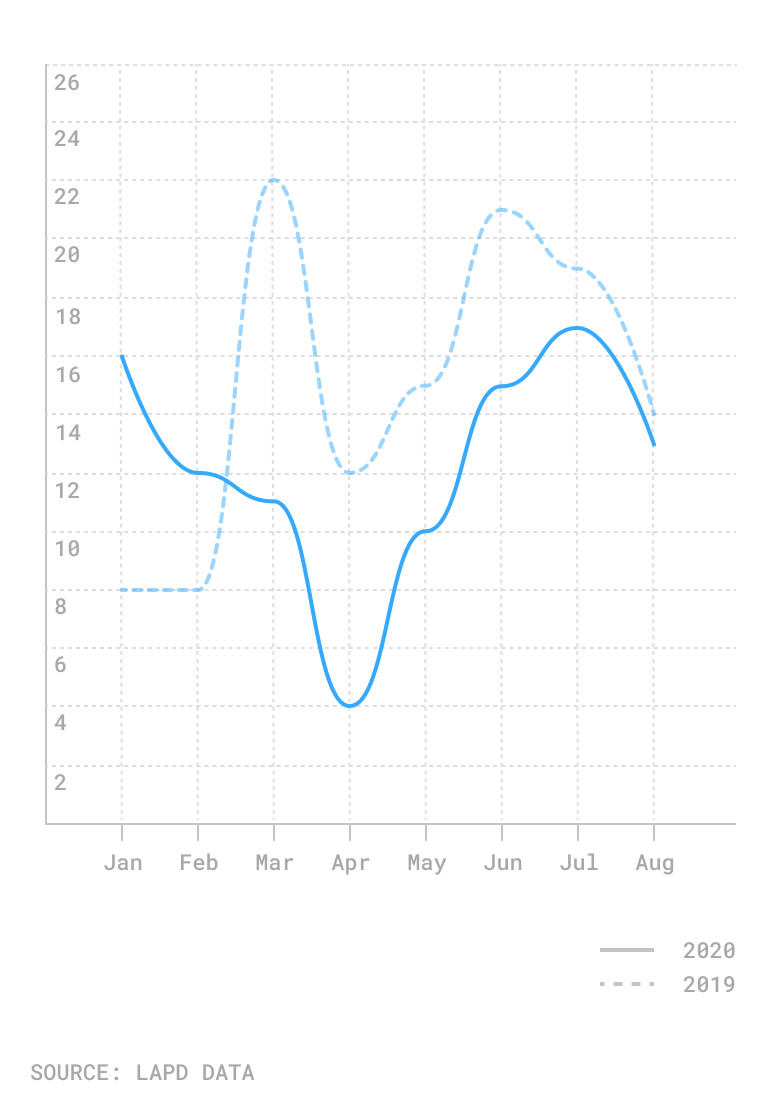

In a downtrodden economy, robberies, assaults, thefts and other crimes committed against street vendors are at nearly the same level as they were in 2019. According to Los Angeles Police Department data, after a sharp decrease in incidents early in the pandemic, there were 17 reported crimes against vendors in July, just two below the same month last year. In August there were 13 crimes committed against vendors; last August the figure was 14.

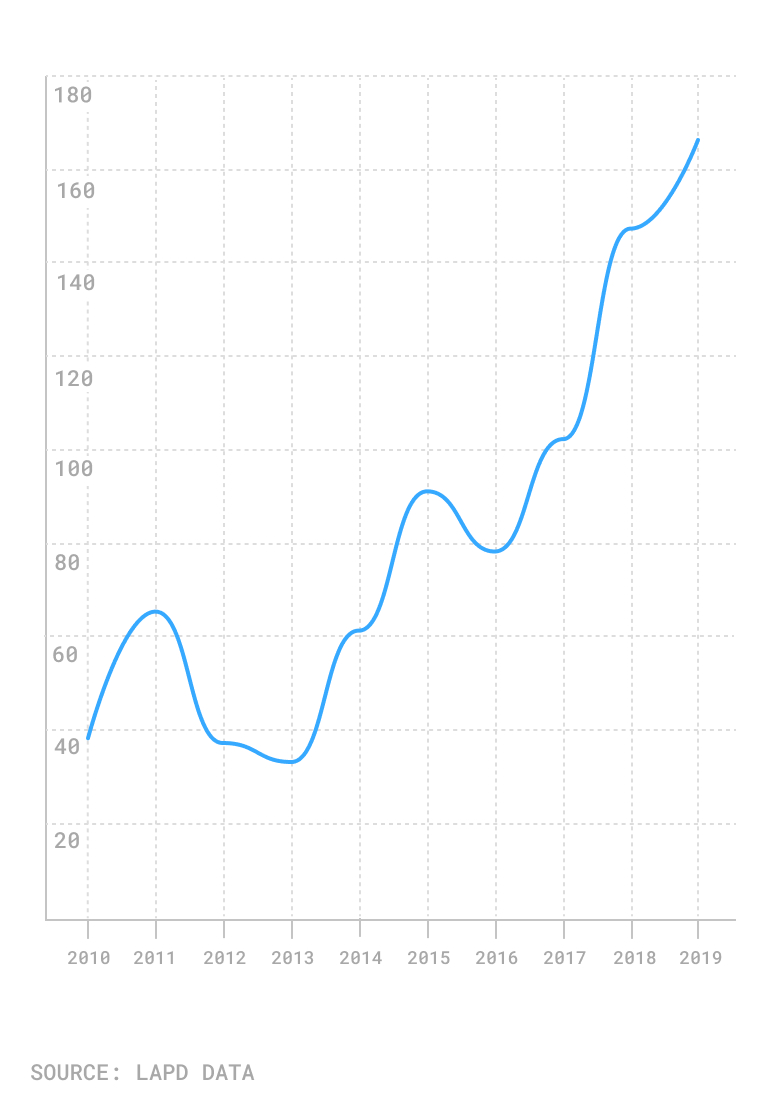

Those figures come on the heels of a steady, decade-long increase. From 2010-2019, reported crimes against street vendors in the city of Los Angeles rose nearly 337%, going from 38 to 166.

Crimes against street vendors in Los Angeles, 2010-2019

“I’m not surprised by the numbers. In fact, I suspect there are more incidents that go unreported,” said Doug Smith, an attorney for Public Counsel, which provides legal support to the Los Angeles Street Vendor Campaign. “In this work, we’ve seen this risk of violence and attacks against the vendor community.”

Dangerous line of work

The year began on a dangerous bent for vendors, as 16 crimes were reported in January, double the figure in 2019. Year-over-year tallies were still high in February, but then the situation changed as the city adopted safety measures to limit the spread of COVID-19. A moratorium on street vending passed by city leaders on March 17 helped reduce the number of criminal incidents to just four in April.

Then figures began increasing, to 10 in May and 15 in June. In the first eight months of the year, there were nearly 100 reported crimes where the victim was a street vendor.

Crimes against street vendors in Los Angeles, 2019 vs. 2020

According to the L.A. Street Vendor Campaign, an advocacy group for the industry, more than 50,000 food, clothing and other vendors operate on the streets of Los Angeles. Approximately 80% of the vendors are women of color. Indeed, according to LAPD data, of the nearly 100 victims this year, only two were identified as white, although the number of male and female victims were about the same.

The neighborhood of Westlake, which is home to MacArthur Park, a longtime hub of street vending activity, was the site of the highest number of incidents during the first eight months of this year, with 28 crimes (compared with 29 at this time in 2019). The second-most impacted neighborhood, Pico-Union, saw six cases.

Cash-carrying victims

Nearly 45% of all crimes against street vendors from 2010-2019 were robberies, according to the LAPD. Approximately 28% of the crimes during that period involved some type of assault.

Officer Drake Madison, an LAPD spokesman, said the department only provides additional patrols to an area being used by vendors if reported crimes are occurring frequently.

“As with all citizens, vendors need to be aware of their surroundings, report any crimes, and vend in groups,” he said.

Smith said street vendors have long been vulnerable in their jobs, and that past laws declaring the practice illegal emboldened criminal predators to target them frequently.

“When you have laws that delegitimize, it sends the signal to the public that people can do the same,” he said.

A push for legalization

After years of work, some change has occurred, and the current criminal dangers come as the city has sought to legalize and regulate street vending. The City Council in November 2018 unanimously approved legislation to allow vending and instituted a permit process. Those operating without a permit can face fines.

The results of the new program have been mixed. Late last year, LAist reported that many street vendors were struggling with the costly and confusing permit system. The pandemic has made these issues worse.

Smith said although he is happy for the legalization effort, it has created additional barriers for vendors, many of whom are low-income, to formalize their business. He charges that the city did not do enough to help vendors get the necessary permits.

Food carts can run from $10,000-$15,000, according to Smith, a steep price for vendors with limited means. He said an additional challenge is that the County Department of Public Health will not issue a permit to sell food unless vendors can certify the cart meets food-safety guidelines.

The City Council recently approved allocating $6 million in CARES Acts funds to help street vendors, according to CBS LA. The Street Vending Recovery Fund will issue grants of $5,000 to pay for supplies and permits so vendors can operate legally.

Smith applauded the move, but noted that it is a competitive process and many people continue to suffer.

“If they make it through the process and get the grant, it still won’t buy them a cart. They are more likely to use that money to support their family,” Smith said. “Some vendors who were saving to meet those costs saw it disappear when COVID hit,” he added.

Smith said that the city limits where vendors are allowed to operate. He recommends that police and local leaders listen to vendors about why they cluster in certain ways. “They sometimes do it to protect each other from violent attacks,” he said. “The city’s regulations on how they can set up aren’t aligned with how they work to protect themselves, and they should allow the creation of special vending districts which would help get eyes on the street and allows vendors to keep an eye on each other.”

How we did it: We examined LAPD publicly available data on reported crime where a street vendor was the victim from Jan. 1, 2010 – Aug. 31, 2020. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. On occasion, LAPD may update past collision reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.