LA expecting another record year for hate crimes

The number of hate crimes reported in the City of Los Angeles in the first nine months of the year increased 14% over the same period in 2019. That puts 2020 on track to have the highest number of hate crimes since the city began making its data public more than a decade ago.

The increase is even more pronounced because overall crime in the city has fallen by 9.7% this year. Experts attribute the rise to tensions driven by the coronavirus pandemic along with the response to mass demands for racial justice.

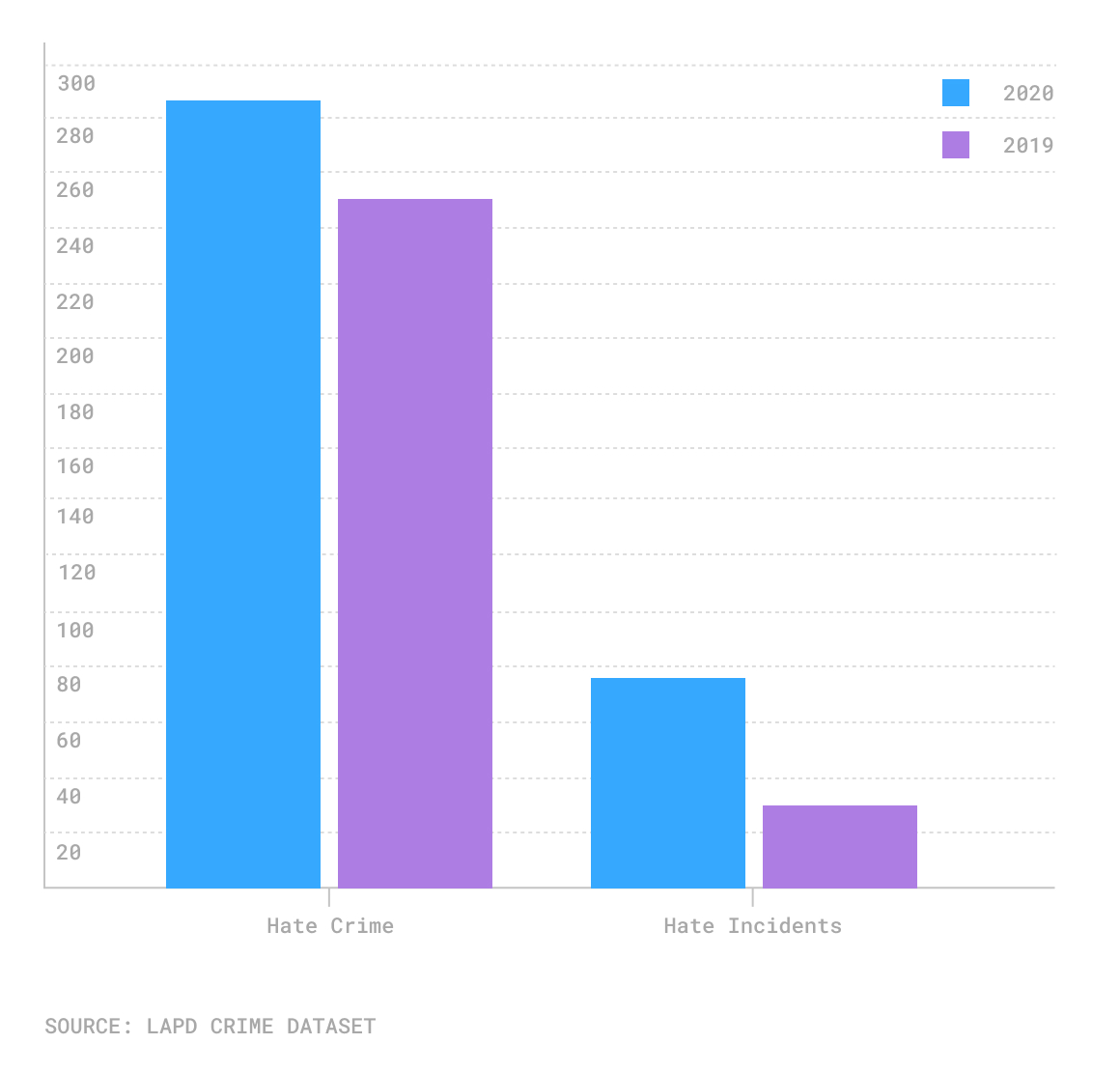

Hate crimes and hate incidents Jan.-Sept., 2020 vs. 2019

“We are hearing reports across the city of an increase in hate incidents of all types– antisemitism, anti-Asian–that followed the COVID-19 outbreak–or acts of racism related to protests following the murder of George Floyd,” said Jeffrey Abrams, regional director of the Anti-Defamation League.

[Related: July marks worst month for murders in over a decade]

According to Los Angeles Police Department data, 287 hate crimes were reported in the city from January to September, up from 251 in the same timeframe last year.

The LAPD defines a hate crime as “any criminal act or attempted criminal act directed against a person or persons based on the victim’s actual or perceived race, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disability or gender.”

These are separate from “hate incidents,” which generally include instances of abuse stemming from racial, gender or sexual-orientation bias, but do not result in a formal crime report. Hate incidents climbed 157% during the same period, with 77 so far in 2020, compared with 30 at the same time last year.

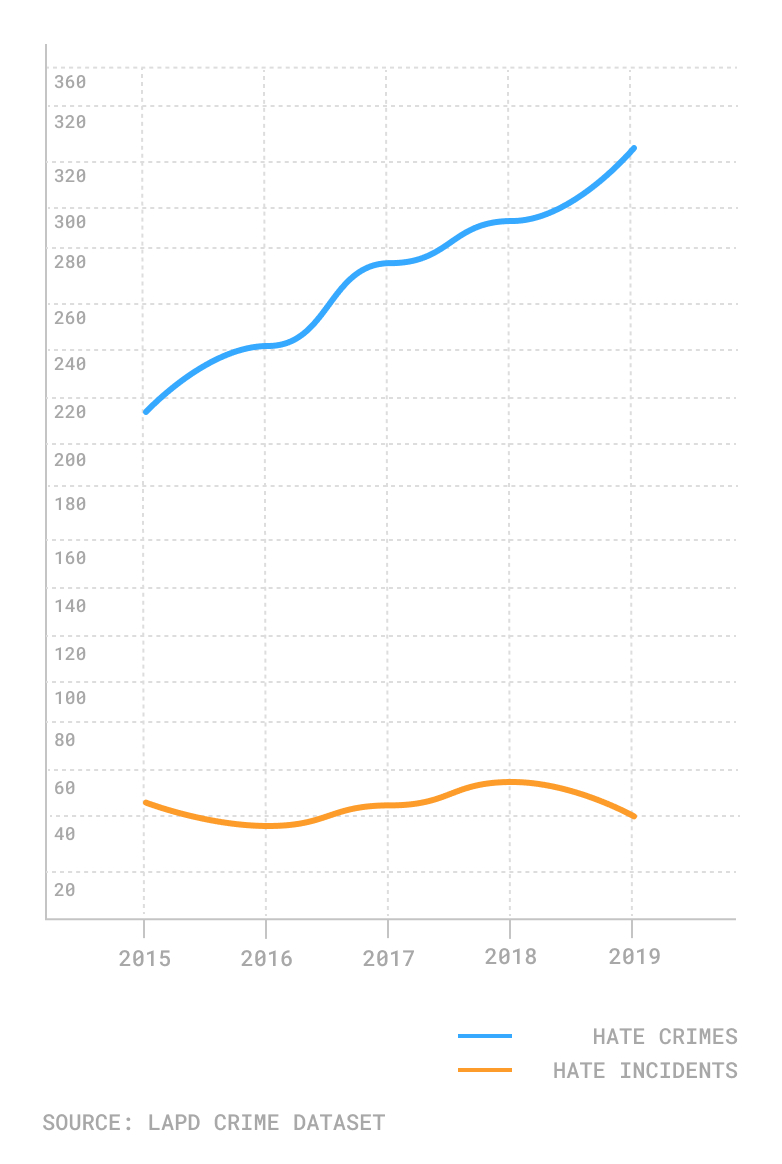

Hate crimes and hate incidents 2015-2019

Rising intolerance

Hate crimes in Los Angeles have risen steadily, spiking 52% from 2015 to last year. The 326 hate crimes reported in 2019 marked a record high, which is now likely to be surpassed by this year’s totals.

Although non-criminal hate incidents have fluctuated during the same time period, Abrams said there has been a dramatic rise in incidents involving antisemitism. An audit by the ADL (which has been collecting its own data from various sources across the country for 40 years) said there were more than 2,100 acts of antisemitic harassment across the United States last year.

Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, says the figures represent an undercount, as many victims of a hate crime or hate incidents are immigrants who have cultural or language barriers that keep them from reporting. Hate crimes are underreported because victims may not trust the police will do anything about it, which is part of the reason the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that less than half of all hate crimes are reported to the police.

“There are all kinds of issues related to reporting. Is the data capturing the full spectrum of inter-group violence? My answer is no,” said Levin. “Unless it rises to the level of spitting in someone’s face or punching them, I don’t think it would show up in those figures.”

There were 158 reports of hate crimes in Los Angeles during the first nine months of this year that involved assault with a deadly weapon, simple assault and criminal threats.

Propelled by politics

Levin said perpetrators typically fall into one of three categories: “thrill offenders” who commit hate crimes for excitement or peer validation; “reactive” or “defensive” offenders who assert they are protecting their neighborhood from encroachers; and “mission” offenders, such as neo-Nazis, who believe everyone beyond them is an “outgroup.”

Levin said that rather than the traditional type of hate crimes, he believes some of what is occurring now is propelled by political motivations, and that he expects a continuation of incidents after the November presidential election.

“It’s going to be an interesting time going forward,” he said. “We are in a new era. The combination of the pandemic and the political circumstance, it will prolong the risk of inter-group conflict.”

Downtown had the highest number of hate crimes in the city so far this year, with 21 instances reported, compared with 20 from the same time last year. Westlake experienced the highest rate of increase, with 14 reported hate crimes during the first nine months of this year, up from five during the same time period in 2019.

There were a couple hate crimes in Westlake. On Sept. 19, someone directed racial slurs at a 52-year-old Hispanic man who was riding a Metro bus. On July 8, a 33-year-old Black man waiting for a Metro Red Line train was confronted by a mentally disabled individual experiencing homelessness. The suspect threatened to stab the man, who police said was targeted because of his sexual orientation.

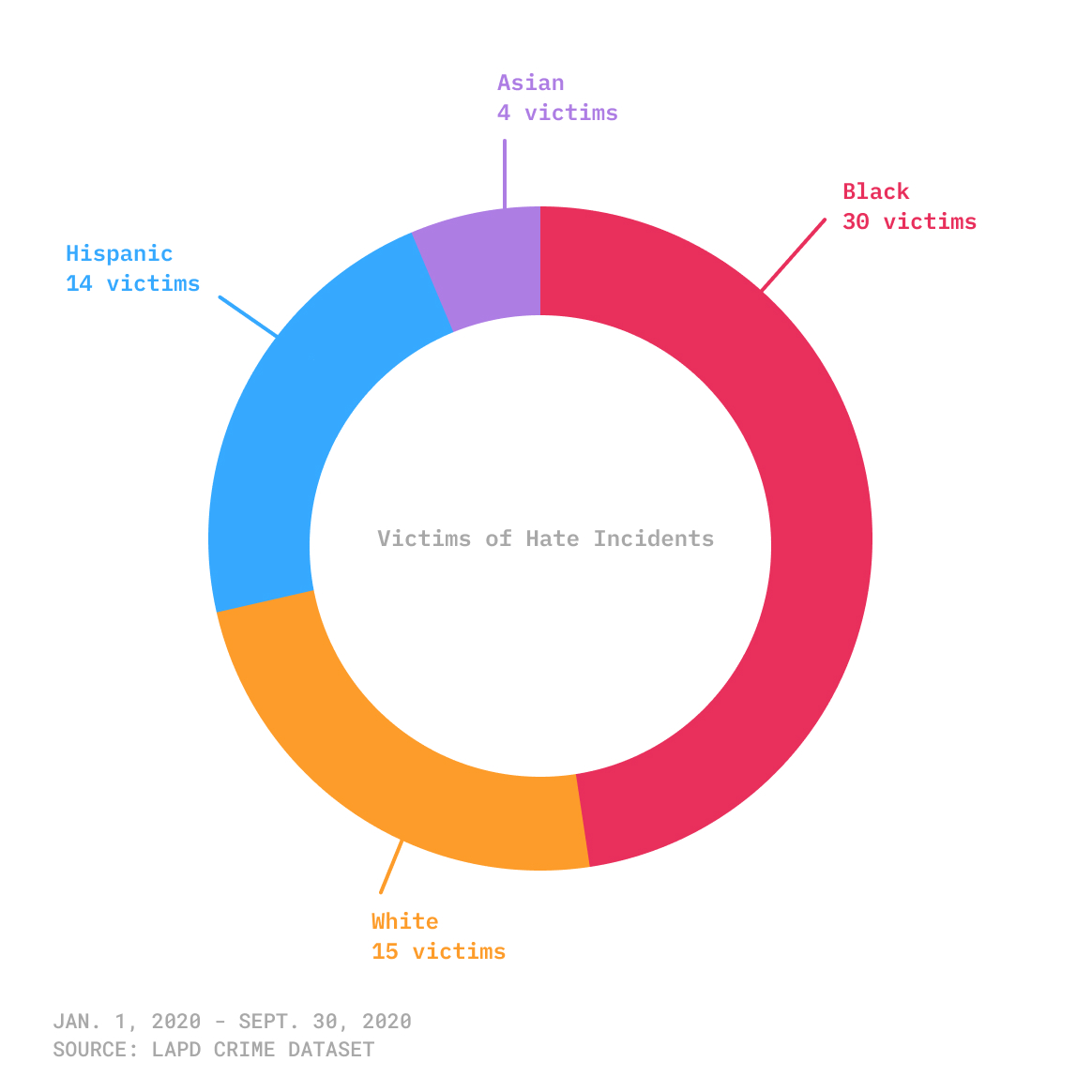

Breakdown of hate crime victims by race

During the first nine months of this year, Black people made up nearly 29% of all hate crime victims, despite representing just 8.9% of the population of the City of Los Angeles. That’s an increase from last year, when Black people accounted for 23% of all victims. The percentage of Asian victims of hate crimes jumped to 4% this year from 1% last year. Across the county, there has been a rising number of threats and hate crimes directed at Asian people, fueled in part by bigotry linking Asian people to the coronavirus pandemic, which saw its first outbreak in China.

Hispanic people were targeted in 27% of hate crimes, while white people made up nearly 22% of victims.

Breakdown of hate incident victims by race

What can be done?

The ADL helped craft the first model hate crime legislation in the United States after the murder of Matthew Shepard, who died in 1998 from injuries after he was beaten and tortured because of his sexual orientation. The ADL has been advocating for reform for social media platforms, urging them to be more aggressive in prohibiting and removing hateful posts. The ADL, in partnership with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, is behind the Stop Hate For Profit campaign that saw national companies pause advertising with social media giants for a month.

The organization was also involved with YouTube’s decision to remove QAnon content. YouTube said it will prohibit content targeting people or groups with conspiracy theories that have been used to justify violence.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has a Hate Crime Rapid Response Team staffed with agents and lawyers who are experts in handling civil rights issues. The Los Angeles Police Department recently changed its reporting to track the prejudice that motivates suspects to target victims. For this and the work done by its hate crimes coordinator, Det. Orlando Martinez, the department has received praise from organizations.

But the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism’s Levin said hate crime laws need to be enforced and the laws updated, particularly for those experiencing homelessness.

“California law doesn’t cover the homeless under hate crime statutes,” he said. “Homeless people are being targeted all the time.”

Last year, there were four victims of a hate crime who were experiencing homelessness. So far this year, one person was the victim of a hate incident.

Dr. Claudia Ramirez Wiedeman, the USC Shoah Foundation director of education and evaluation, said there is a need for empathy now more than ever.

She pointed to a study that found that students who learned about the Holocaust through survivor testimony (the Shoah Foundation has videotaped thousands of interviews with Holocaust survivors) show higher critical thinking skills and a greater sense of social responsibility and civic efficacy. The study found that students “may have greater comfort with people of different backgrounds, greater openness to viewpoints different from their own, and a greater sense of responsibility to help others who are less fortunate.”

“The pandemic and a contentious election season is a time when everyone is having feelings, whether it be despair, grief, isolation, resentment, disconnection or hate,” said Wiedeman. “Empathy helps to notice and reject stereotypes, respect and value differences and enlarges people’s sphere of concern. Developing empathy means understanding that it’s not just about me, it’s about everyone around me. During this time, it’s especially difficult because everyone is isolated and more likely to think about themselves and their self-interests.”

How we did it: We examined LAPD publicly available data on reported hate crimes and hate incidents from Jan. 1, 2015 – Sept. 30, 2020. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. On occasion, LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.