As more graffiti goes up, a debate about what to take down

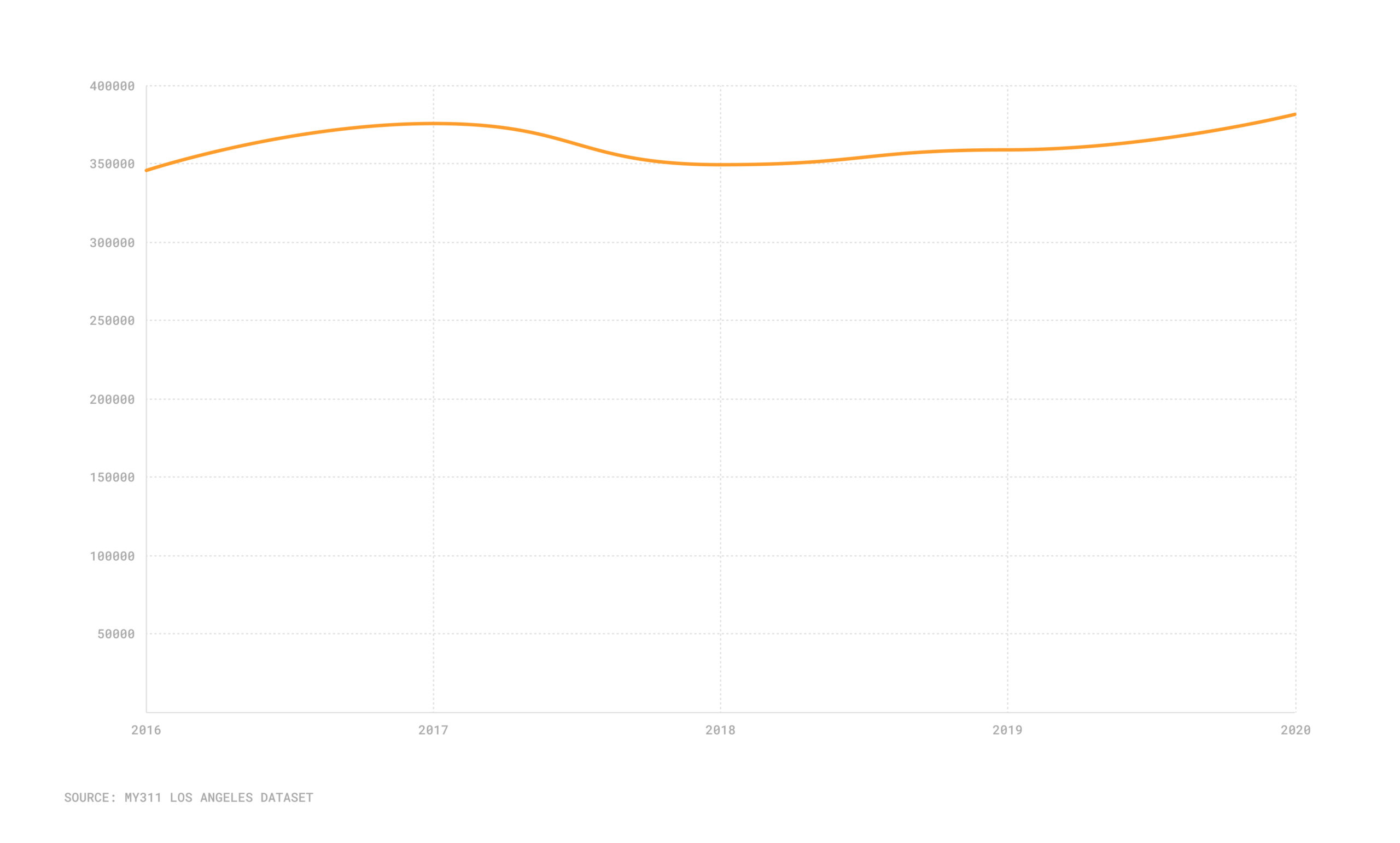

Last year, Los Angeles residents submitted 343,246 graffiti removal requests, according to My311 LA data, a 6% increase from 2019, and the highest number in at least five years. That kept the city busy: It removed 27.9 million square feet of graffiti—an entire square mile—last year.

Graffiti complaints in Los Angeles, 2016-2020

The city has one core requirement when deciding whether to remove the graffiti from private property: Whether the artist had the permission of the property owner to put something on the wall.

“It could be a beautiful piece of artwork, but if it was put up without the consent of the property owner then it is considered vandalism,” said Paul Racs, the director of the city’s Office of Community Beautification.

Jason Saboury, a graffiti artist in Los Angeles, disagrees. “I believe it’s more than that,” he said. “I’m a sociopolitical artist.” He once spray painted, “Plant hope in your heart’s wounds,” a poem by Alexandra Vasiliu, across the wall of a white industrial building, and, “You may encounter many defeats but you must not be defeated,” from poet Maya Angelou.

The increase in calls for graffiti removal is resurfacing an age-old debate about who the gatekeepers of art in Los Angeles are. Rapid gentrification, recent protests for social justice, as well as graffiti wars between gangs, are complicating the issue even more.

Mural of Kobe Bryant and Nipsey Hussle at 3838 S. Hill St., by @sergileto and @jonzenderart. Courtesy of kobemural.com

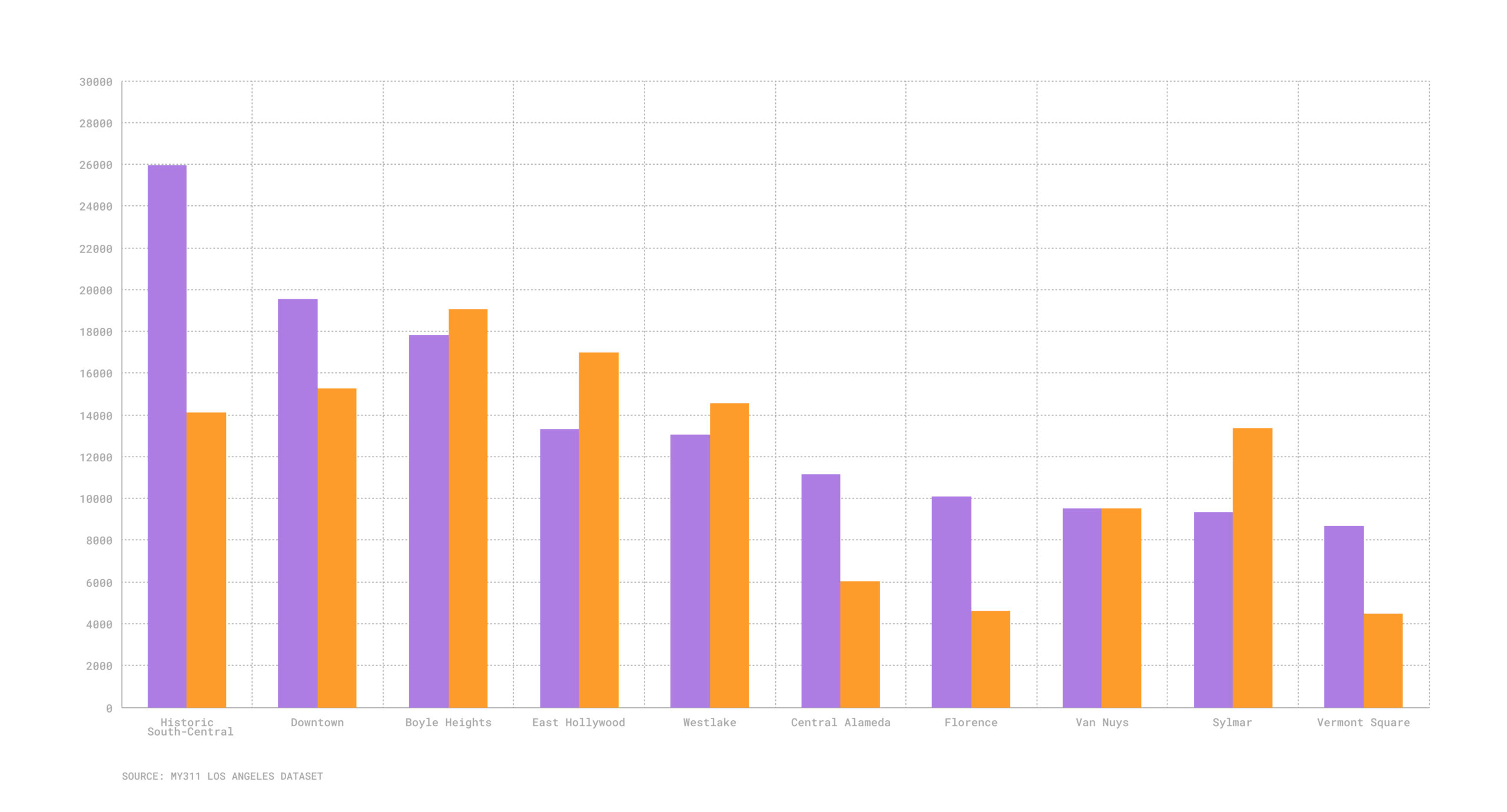

Last year, the neighborhood of Florence, in South Los Angeles, recorded 10,081 graffiti removal requests, a nearly 118% increase from 2019.

According to Xio Sandoval, a real estate agent with Century 21 Realty Masters who operates in Florence as well as other neighborhoods, the sharp increase can be explained by one reason only: gentrification. That’s when wealthier, often white homebuyers flood a poorer neighborhood, driving up prices and displacing many of the long-term residents in the process.

Sandoval concedes that there is a lot of graffiti in Florence. But what’s changed is that new residents who were priced out of sky-high housing costs on the Westside of Los Angeles have moved in, and are likely complaining about it to the city’s My311 service more frequently.

“New homeowners are open to graffiti artist murals, but not gang graffiti that claims neighborhoods,” said Sandoval. “I believe in 10 years everything in Los Angeles is going to be gentrified.”

Los Angeles County home prices have been increasing for years; in December they rose 11% from a year earlier.

But the relationship between graffiti and home prices is complicated. The Los Angeles Police Department insists that more graffiti in a neighborhood means a message is being sent that “nobody cares,” which sets off a “vicious cycle that encourages further crime.”

However, a 2016 study conducted by the Warwick Business School found that in London there was a correlation between street art and property values: They went up together. The same study found that as crime decreased in the United States in the 1990s, graffiti drove home prices up in cities where affluent college graduates were seeking an “authentic urban culture.”

The term graffiti encompasses a wide array of street art, from simple tags, where the author leaves behind a stylized signature, to elaborate murals.

Mural courtesy of Shandu One, Lincoln Heights, 2017

Hector “Shandu One” Calderon, a pioneer of graffiti art in Los Angeles, says that the tension between gentrification and graffiti has been around for years. He recalls that some of the earliest work he did, in the Belmont Tunnel, part of an abandoned trolley line in Westlake, were removed when new housing was constructed nearby.

Calderon says the debate about whether graffiti is art or not has a new arbiter: Instagram. “‘Likes’ make graffiti more artful,” he said. “There are people out there that have never done graffiti and all of a sudden they have 10,000 people following them for writing on a wall with graffiti. After Banksy, everyone became a graffiti artist because social media blew it up.”

Calderon, who currently does graffiti art tours, said graffiti writing had been an alternative to going to jail or joining gangs when he was younger. He considers himself a writer leaving his mark on the world to say, “I was here.”

But his moniker initially was more of an alter-ego, as part of the fun was being anonymous. “When I started graffiti in 1984, I wrote Shandu One,” he said. “It was just a name that I picked from a movie that was a genie. No one would know Shandu One from Hector. I would write it everywhere, but couldn’t tell anyone that was me. People would say, ‘I know this guy!’ and I would stand next to them and be like, ‘Who the hell is this?’”

Calderon noted that there is big business around graffiti, from a massive spray-paint industry to the contractors who are paid to whitewash it. “Graffiti is actually just another mechanism for people to make money. The contractors who are coming out to remove graffiti are charging the city,” he said.

Racs, the director of the Office of Community Beautification which operates a graffiti removal program for the city, said they responded to about 30% of overall graffiti removal work last year; the other 70% was the “result of proactive removal by contractors.” Some of those contractors are community-based organizations that use people needing to complete community service hours for the court system, according to the office’s website.

Before and after, courtesy of Office of Community Beautification

Van Nuys is another neighborhood that ranks in the top 10 for requests about graffiti removal. Last year, it registered 9,513 complaints, the same number it had in 2019. Mike Browning, president of the Van Nuys Neighborhood Council, believes that graffiti actually became more prevalent last year in parts of Van Nuys. He says people might not have noticed it as much because Van Nuys was a COVID-19 hot spot, which meant fewer people were out to complain about it. He also said it could be reporting fatigue (residents get tired of asking the city to remove graffiti), which meant graffiti stayed up longer. He added that many of the sites with graffiti were businesses that took it down themselves instead of reporting it.

Neighborhoods with the most graffiti complaints, 2020 vs. 2019

Marking territory

Ben “Taco” Owens, a gang-intervention worker, says there can be a coded message in the graffiti that, if not addressed properly, can lead to violence. He calls My311 LA if he thinks someone will get hurt due to gang writing, but does not call in tagging if there is no threat attached to it.

“There’s a saying when we see gang graffiti: ‘When the graffiti goes up, the bodies go down,’” Owens said. “It’s only a matter of time before a rival gang member gets caught scratching out the graffiti and getting hurt, so we try to get it down as soon as possible. Some people may think it’s a peace sign, but it’s really a gang sign.”

Owens said sometimes gangs use monikers that will claim an entire city, like the Gardena-13 (also known as Gardena Trece), which can be hard to distinguish from graffiti artists who are doing it to show community pride. Owens admits it can be difficult for the average person to distinguish gang-related graffiti writing from art, but insists the message behind the graffiti is what determines if it will lead to something bad.

“There are a lot of graffiti murals popping up for Kobe Bryant and victims of officer-involved shootings like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” said Owens. “Some people don’t want gang writing on the walls, but will be okay with those or someone writing ‘F— Donald Trump.’ Is that offensive to someone in the community? It boils down to how it’s interpreted and what that statement means.”

Staying power

There are ways that graffiti can become an officially sanctioned part of the cityscape. The Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs is responsible for, among other things, creating public art meant to “ignite a powerful dialogue, engage L.A.’s residents and visitors, and ensure L.A.’s varied cultures are recognized, acknowledged, and experienced,” according to a 2020 press release. Artists can apply for an original mural registration to create on private property.

Saboury, the sociopolitical artist, is trying to find a way to protect street art from being caught in the endless cycle of appearing on walls only to be taken down later by the city. He launched Santee Public Gallery, a free and open space Downtown for artists who want to pick up a spray can to be creative. After Saboury organized business and building owners, they agreed to allow artists to paint their exterior walls, and guest curators and artists will get to envision the space their way for six months at a time, according to Saboury. He hopes more businesses are open to this in the future.

He says that finding a way to allow this kind of expression is more important than ever. Saboury, whose father is Iranian, said he began his work in response to Trump’s 2017 Muslim travel ban. “It made me feel for the first time in my life like I wasn’t American even though up until that point I was serving my community.”

Graffiti hunting has also become a form of tourism. Kevin Flint, the spokesperson for LA Art Tours, said more than 20,000 people from around the world have attended their tours.

“There’s a certain coolness to graffiti and street art,” Flint said. “All the local schools go on our tours and the kids love it.”

How we did it: We examined publicly available My 311 data. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.