Car repossessions stall during pandemic, despite the bleak economy

Unemployment claims skyrocketed during the coronavirus pandemic and many struggled to meet the monthly rent challenge. But the number of car repossessions reported to the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department took a surprising turn: It went down.

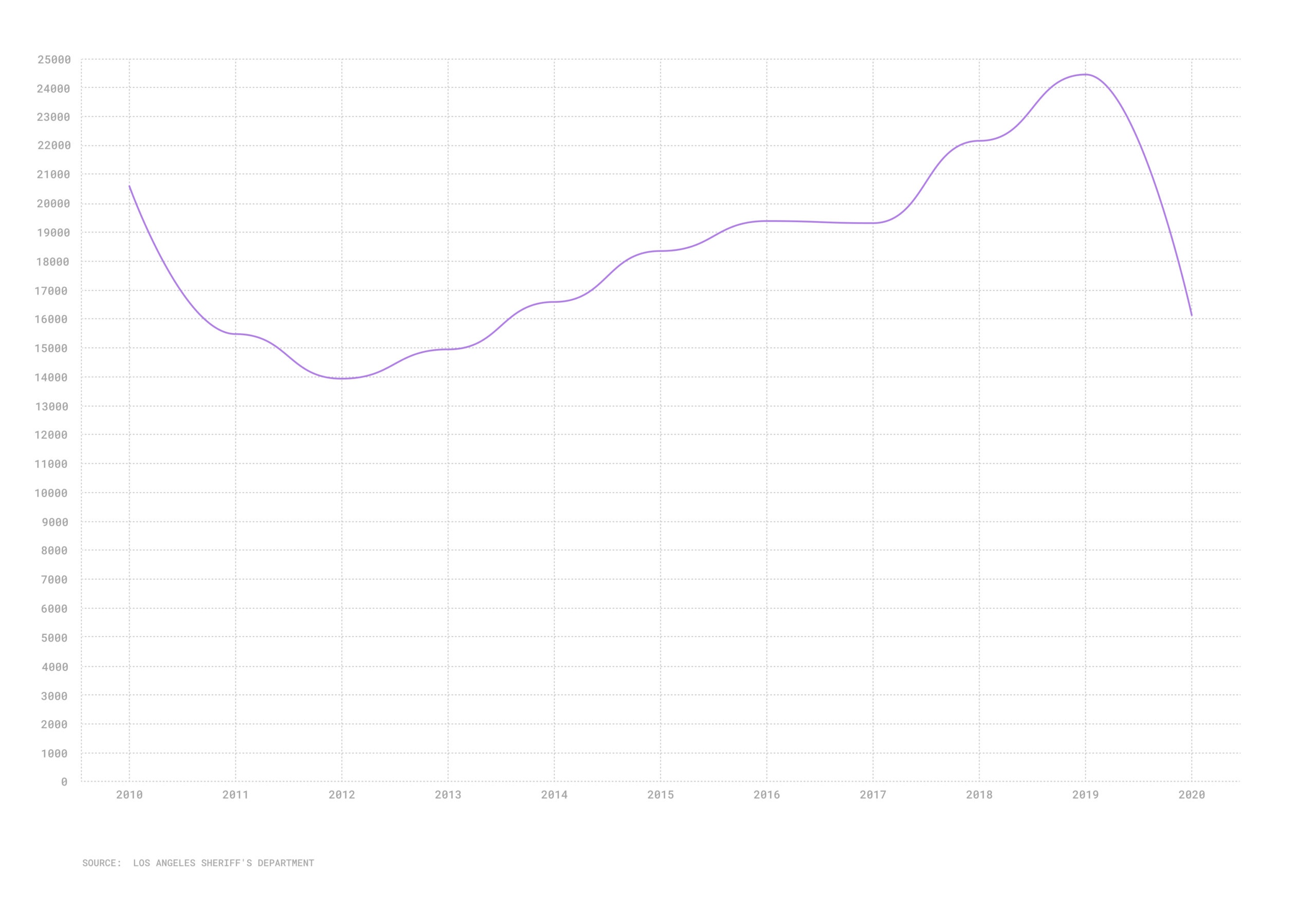

There were 16,142 repossessions in 2020, a 34% drop from the 24,462 reported the previous year, according to LASD data. The 2020 tally was also the lowest annual figure since 2014, when 16,585 vehicles were repossessed.

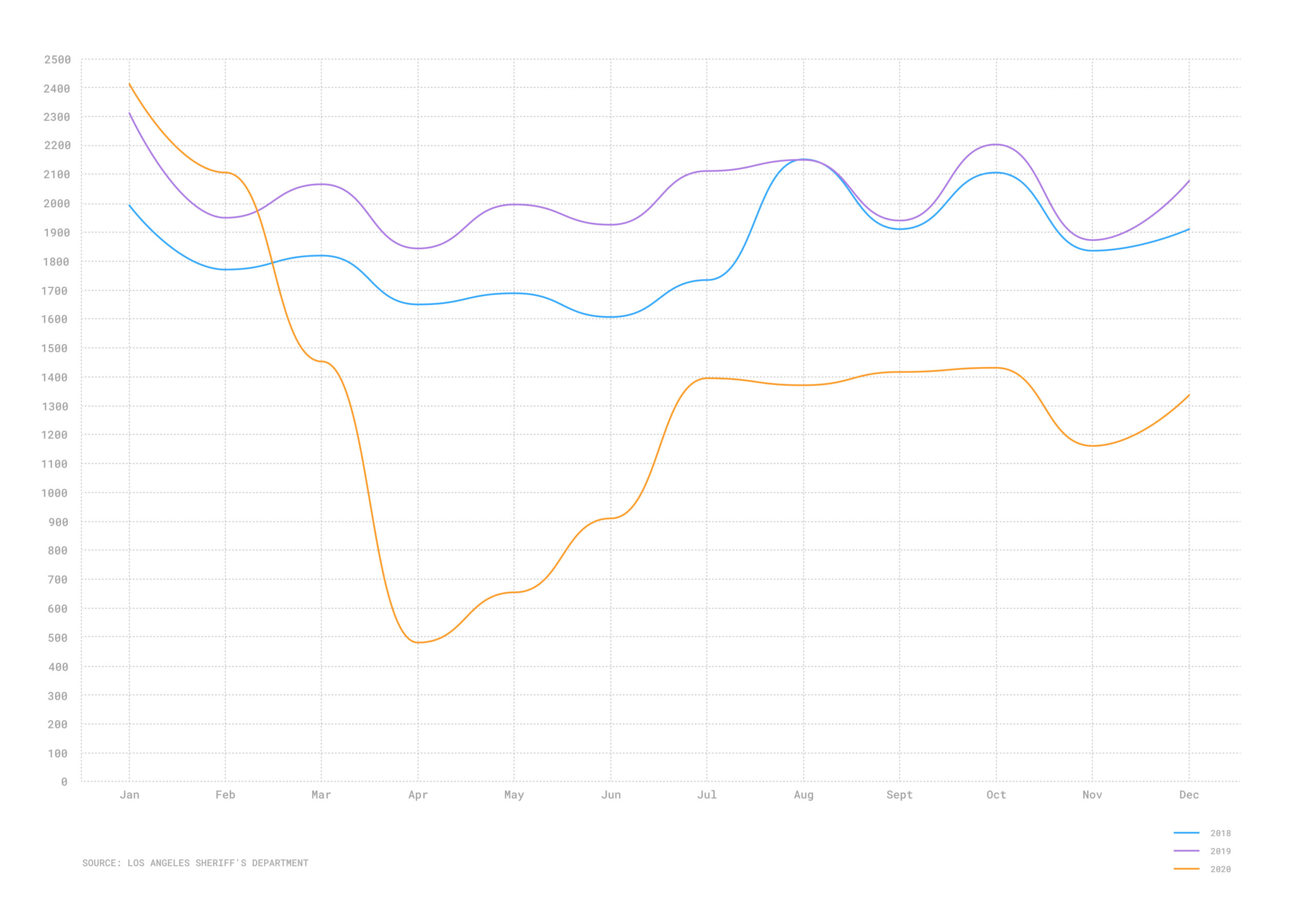

Car repossessions in Los Angeles County by month, 2018-2020

The drop stands out in part because, early in 2020, repossessions were rising; the totals in January and February were both higher than in the same month in 2019.

The situation reversed once widespread business closures took effect. There were 1,454 repossessions reported in March, down from 2,109 in February. The decline was even steeper the next month; the 481 repossessions in April marked a nearly 74% drop from the 1,844 repossessions in April 2019.

May and June also had repossession numbers that were less than half the total in the same month the previous year.

The reason: Some big finance companies halted the practice at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. An employee at RWA Repossession named Jonathan, who declined to give his last name because of the sensitive nature of the business, said the large credit firms that use his company to take possession of vehicles just stopped calling as much.

“We actually thought they would pick up, but finance companies didn’t want cars repo’d and we ended up losing work,” Jonathan said. “A lot of my drivers were sitting home from March through July.”

Credit hit

A vehicle repossession happens when someone finances or leases a vehicle, stops making payments, and creditors take back the car without an immediate warning, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Once a creditor has possession of the car, they usually resell it.

LASD repossession data provides a glimpse into the economic hardship many people were facing even before the pandemic. In addition to losing the primary way someone gets to work, school or the grocery store, a car repossession can destroy an individual’s credit, making it more difficult to secure a future loan, or causing the person who gets a loan to pay a higher interest rate.

Nisha Kashyap, a staff attorney with the Consumer Rights and Economic Justice division of the pro bono law firm Public Counsel, said car repossessions were an issue even before the pandemic. She added that some clients who lost their jobs during the pandemic were unable to get work after their car was repossessed, further exacerbating the situation.

“Losing a car in a sudden way can be really damaging,” she said. “In most instances of repossession, there isn’t a notice that is given before the repo, so it can be done without any warning once a consumer has defaulted on a loan.”

LASD spokesperson Deputy Trina Schrader said finance companies will usually contact a tow company to repossess a car, and after the vehicle is taken away, the company will call the local sheriff’s station to report the vehicle that was picked up and the address.

“We do have repo companies that contact us at the station within that jurisdiction to let us know they did repossess the car and let us know that it wasn’t stolen,” she said. “It’s mostly so we can direct a person when they call us to report their car stolen, so we can tell them where the car is located and give them the contact information for the finance company.”

Although repossessions were down in the pandemic year, they had been steadily increasing since 2012, with a nearly 27% jump from 2017 to 2019 alone.

Car repossessions in Los Angeles County, 2010-2020

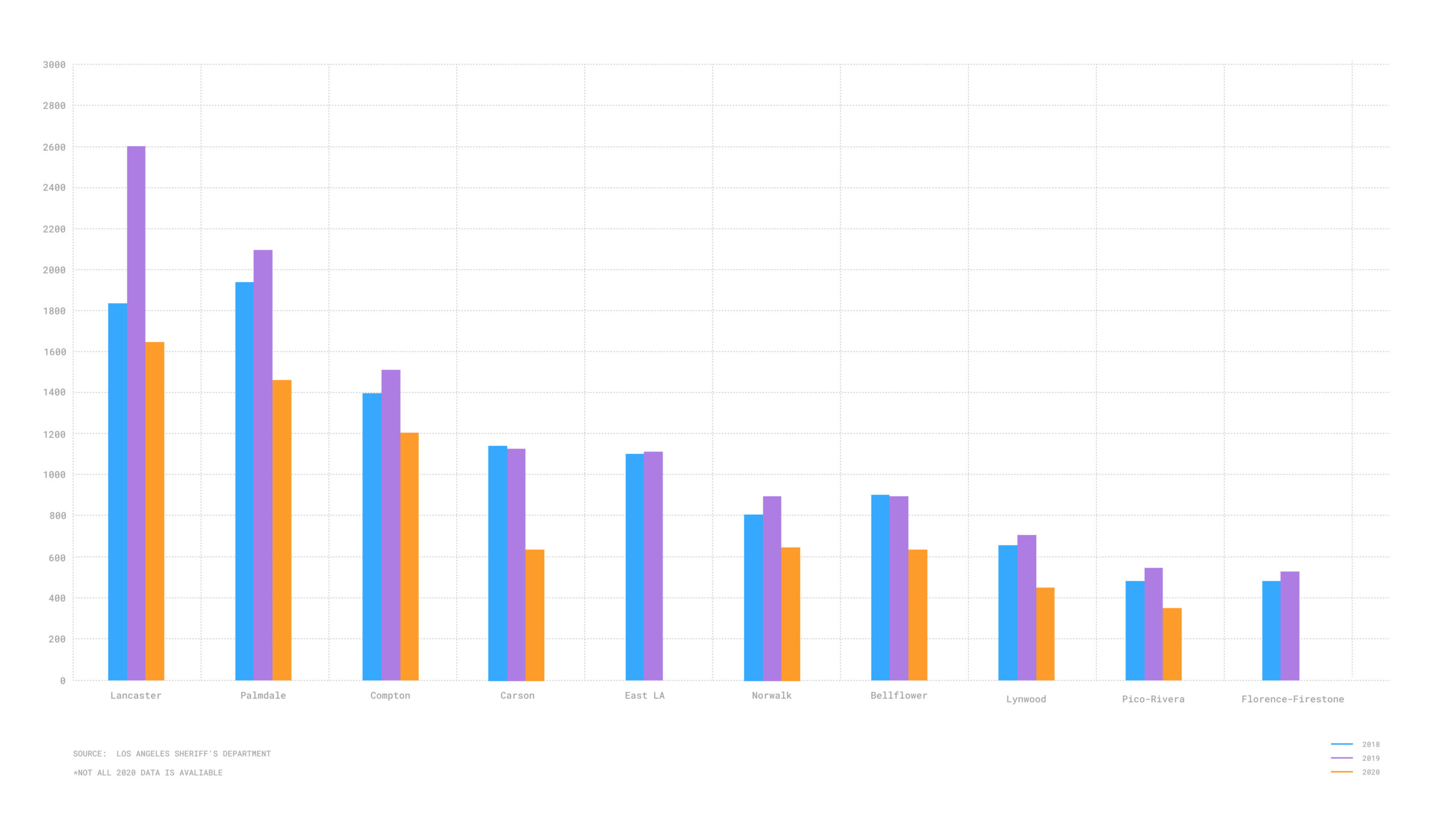

Car repossessions occur most frequently in low-income communities. In 2020, the neighborhoods of Compton, Lancaster, Palmdale and Pico-Rivera had a combined 4,673 repossessions. Meanwhile West Hollywood, Malibu, Palos Verdes and Calabasas had a cumulative total of 131.

That doesn’t mean people in wealthier areas were always up to date on their car payments. Jonathan said his company rarely gets requests for luxury vehicles such as Porsches because “rich people have garages, and we can’t go in there to get a car back unless it’s a public garage.”

He added that his company most often gets repossession requests for “everyday cars,” such as Hondas and Hyundai Elantras.

Car repossessions by neighborhood, 2018-2020

Some people who have had vehicles repossessed say they have been unable to retrieve possessions that had been left in the car. Kashyap said someone who had a car repossessed is entitled to get their property back, though that can be more difficult if the car has been hauled to a location far from the individual’s home.

“If you just lost your car you may not have a way to get deep into the Valley, for example, to get your personal belongings,” Kashyap, the consumer rights attorney, said. “For folks who have paperwork or medication when it’s repossessed, it can be very difficult to get that back.”

Jonathan said repossessing vehicles is harder than it once was because of television shows like “Operation Repo.” The reality program, which ended its TruTV run in 2014, but is still available in reruns, depicted the world of car repossessions in the San Fernando Valley.

“TV shows let people know about how cars are tracked so it kind of burned it for us,” he said.

Predatory loans

Kashyap said repossessions are a symptom of a larger problem of loans with “extremely high” interest rates and “unaffordable terms.” She pointed to a Wall Street Journal story about borrowers falling behind on car payments, an indicator of how the economic recovery from the pandemic is unequal.

“That in itself is a symptom of financial distress,” she said. “Repossessions are the natural consequence of that.”

Kashyap said a better way to address these matters is to improve lending practices and access to credit so people are not burdened with high-interest loans they can’t afford.

“Transportation is a necessity in L.A.,” she said. “How do you have access to transportation in a fair way that doesn’t result in this cycle that further damages your credit which leaves you stuck in another high-interest rate loan?”

Kashyap added that for people in Los Angeles who use their car for shelter when communal shelters may not be the safest option, repossessions can have “devastating consequences.”

How we did it: We examined publicly available repossession data and from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department from Jan. 1, 2010-Dec. 31, 2020. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LASD data only reflects repossessions that are reported to the department, not how many actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LASD makes publicly available. LASD may update past reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.