Crime at tent encampments rises during the pandemic year

When Mayor Eric Garcetti last month announced in his State of the City address that Los Angeles would invest $1 billion to combat homelessness in the coming fiscal year, it was met with both applause and skepticism. The following day, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter decided things were not moving fast enough and ordered the city to provide shelter to people experiencing homelessness on Skid Row by October.

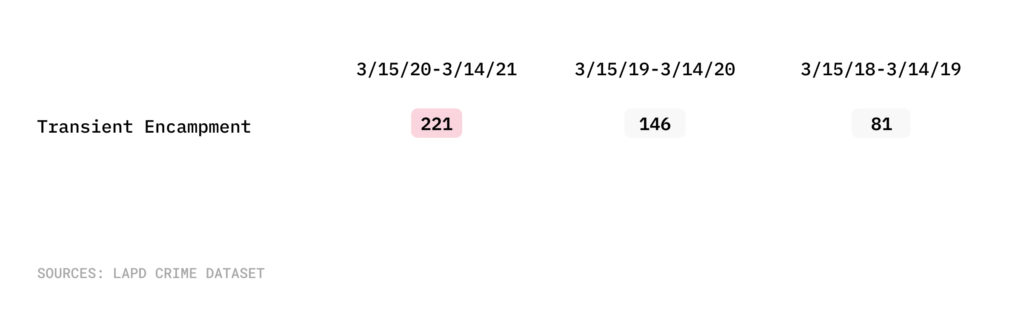

The attention comes as the situation on the streets is growing ever more dire, with a surge of crime occurring in tent encampments. From March 15, 2020 (the day Garcetti ordered the closure of many businesses in Los Angeles due to the emerging coronavirus) through March 14, 2021, there were 221 incidents of crime reported at a homeless encampment, a 51% increase from the 146 in the previous 12-month period, according to Los Angeles Police Department data. That figure is also a nearly 173% jump from the 81 reported two years prior.

Crimes at tent encampments, pandemic year versus two prior years

“The crime on Skid Row has skyrocketed,” said Rev. Andy Bales, president and CEO of the Union Rescue Mission in Downtown. “We used to have a rare occurrence of shootings. Now we have them every week. People are suffering from robberies, rape, hunger, the cold or heat—you name it. I don’t know if there’s a place anyone can suffer more. It’s an absolute disaster.”

[Get COVID-19 and crime stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter.]

The situation on Skid Row, where an estimated 4,662 people live on the streets, according to a 2020 count by the Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority, provides a glimpse into how mental health service failures, economic disparity, housing discrimination and systemic racism have led to an increase in crime at homeless encampments across the city during the year of the pandemic.

Commander Donald Graham, Jr., the homeless coordinator for the Los Angeles Police Department, said the increase in crime in encampments can be attributed to the City Council’s pandemic decision to halt clearing tents and impounding vehicles used as dwellings. This was in the wake of Centers for Disease Control guidelines that encampments be allowed to stay in place so as not to spread COVID-19.

“An unfortunate consequence of this has been a massive increase in the density of the encampments,” Graham said. “Even vehicles parked on the roadways have become de-facto encampments.”

The community of Venice reported 50 criminal incidents at encampments, the highest number in Los Angeles. The second most-frequent community for crime reported at encampments was Koreatown, with 26.

Community members in Venice have attributed the rise to fewer police at places like the boardwalk, as well as turf battles.

Dr. Robin Petering, the policy co-chair for Ktown for All, a community organization that supports people experiencing homelessness, said there is a lack of access to drop-in centers and other resources due to the pandemic. That, she said, means some people experiencing homelessness are looking for other ways to gather the resources they need to survive.

“People living on the streets experience far more violence than the housed population due to lots of reasons like exposure and people trying to exploit them,” she said.

To reduce the number of new people falling into homelessness, Petering said the City Council should prioritize protecting renters and low-income tenants by exploring options such as rent freezes and more hotel/motel conversions. City leaders and others have also discussed the importance of homelessness prevention.

“We need to be doing a lot and a lot faster,” Petering said.

Danger of assault

Assault with a deadly weapon, a felony, was the most frequent crime reported at tent encampments in the pandemic year, with 82 incidents, up from the 39 reported in the previous 12-month period. The 22 robberies marked a 144% increase from the eight in the prior 12-month period.

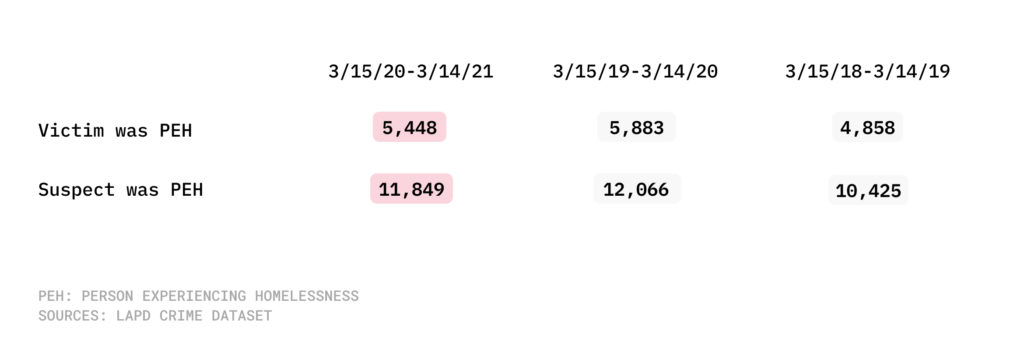

Despite the increase in crime at encampments, there were fewer reports citywide involving victims and suspects experiencing homelessness.

From March 15, 2020-March 14, 2021, there were 5,448 instances of crime in which a victim was experiencing homelessness, down 7% from the previous 12-month period. Crimes involving a suspect who was experiencing homelessness fell by almost 2%.

Crimes involving people experiencing homelessness

Housed communities in Los Angeles also spent less time calling to complain about encampments. The city’s 311 call center fielded 47,283 calls about homeless encampments. Although that translates to about 129 a day, it is a 20% drop from the roughly 59,000 calls made during the previous 12-month period, according to My 311 LA data.

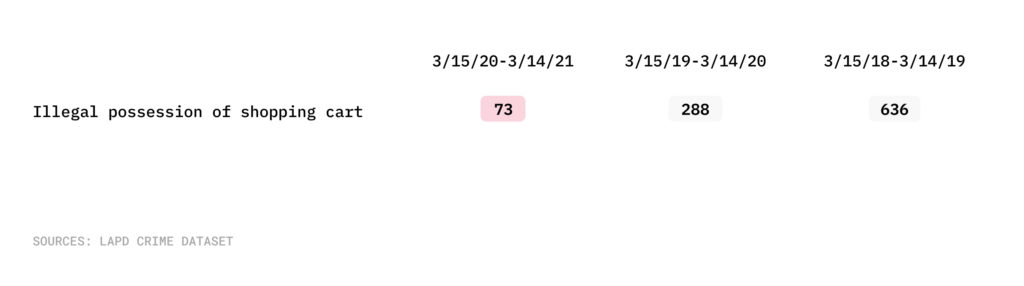

There were other unique patterns during the pandemic year. Police made 73 arrests for illegal possession of a shopping cart, a nearly 75% drop from the 288 arrests made during the previous 12 months. This also marks an 88.5% decline from the 636 arrests made two years ago.

Arrests for shopping cart possession

Graham said 25 years ago, handing out citations for illegally possessing a shopping cart was a tool used to deter people experiencing homelessness from collecting massive amounts of property on the streets. He said the department’s philosophy toward homelessness has changed, and that many officers seek to connect people experiencing homelessness to services.

“The problem isn’t the shopping cart and it doesn’t abate the problem of the person who doesn’t have a home,” he said. “Getting a homeless person off the street is our goal. If your only crime is having a shopping cart to store your belongings, we’d rather try to get you into housing.”

The Union Rescue Mission’s Bales said he is happy the police have given up on enforcing mandates on shopping carts and are focusing more on addressing real crime at homeless encampments. However, his greater worry is what he views as a slow approach in getting people off the street, and a misguided over-reliance on the construction of permanent supportive housing projects, with too little money directed at shelters and other short-term or “bridge” solutions.

“We can’t keep the status quo when people are dying,” Bales said. “The answer to people suffering can’t be slow-to-arrive, expensive units that only help a few while leaving many on the streets.”

How we did it: We examined publicly available My 311 data and crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from March 15, 2018 – March 14, 2021. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.