The problematic ties between homelessness, mental health and crime

Mental-health issues are a prevalent and ongoing concern in addressing homelessness. That includes how already vulnerable homeless populations are exposed to crime.

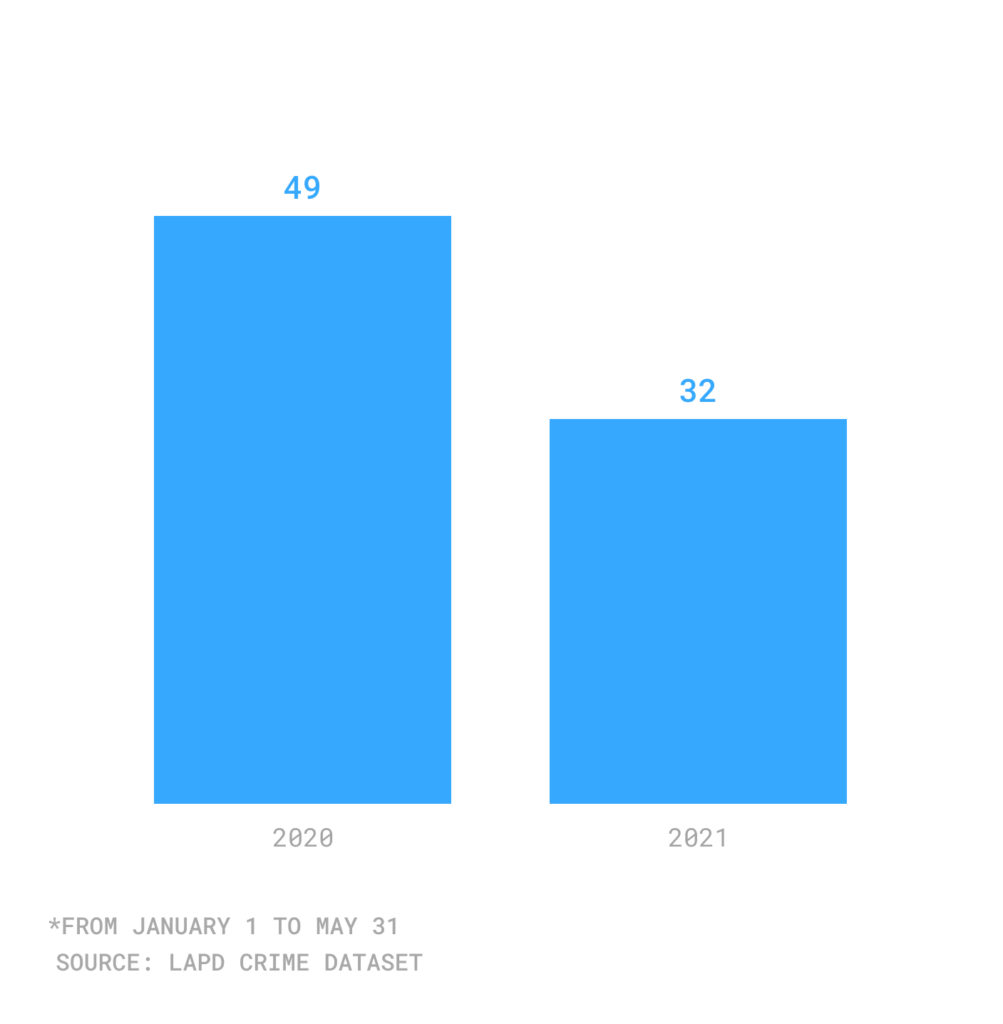

From Jan. 1-May 31, there were 32 instances of crime reported that involved an unhoused person who was also suffering from mental health issues, according to Los Angeles Police Department data. That is actually down from the 49 reported during the same time last year.

People experiencing homelessness and suffering from mental illness who were a victim of crime, 2021 vs. 2020

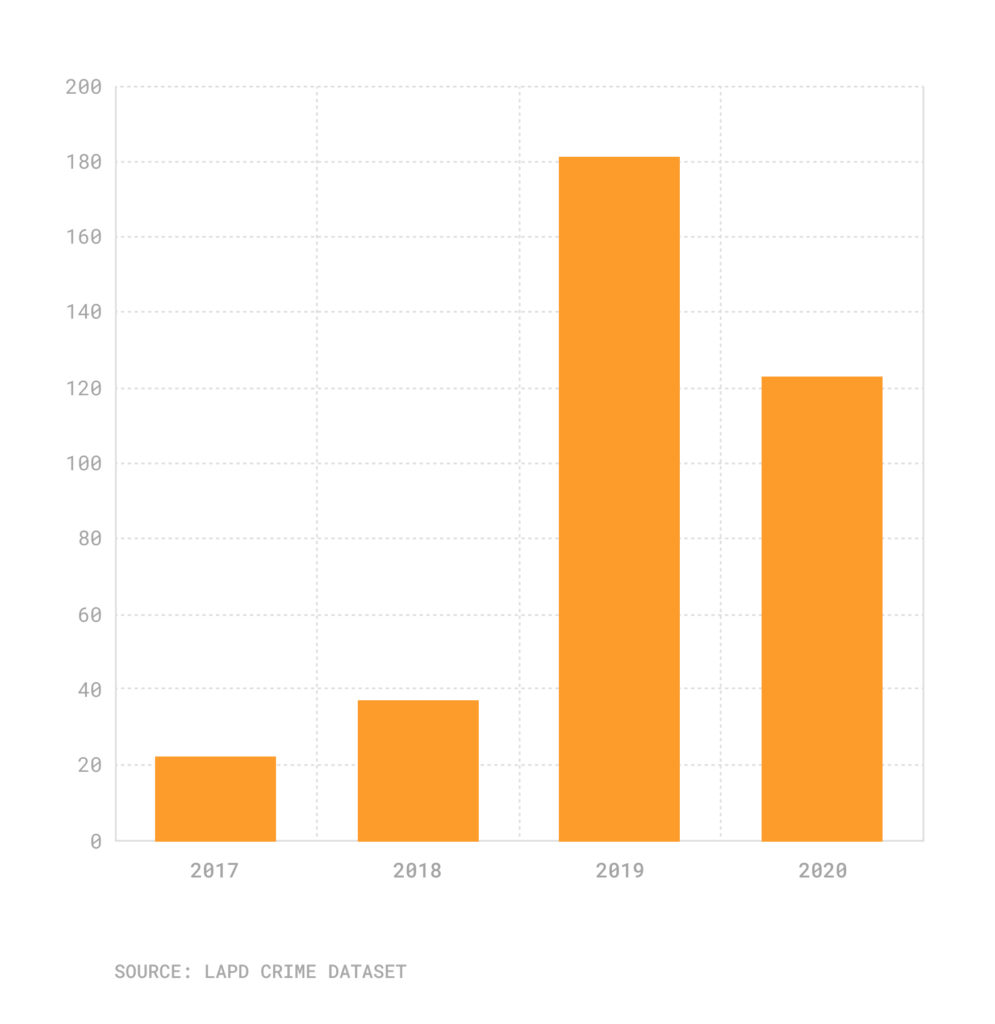

In 2019, the LAPD recorded 181 instances in which a person experiencing homelessness and suffering from mental illness was a victim of a crime. In the previous nine years the annual number had not exceeded 37 crimes.

Commander Donald Graham Jr., the homeless coordinator for the Los Angeles Police Department, said the primary reason for the spike in 2019 was because the department implemented new training on how reports are classified, in the effort to ensure that crimes involving a homeless suspect or victim are accurately recorded.

“That is in addition to the increase in mental illness calls we get as a department,” Graham said. “Encampments used to be more out of the public eye so the police wouldn’t get called. But as homeless encampments became more prevalent we got numerous calls, especially if people are having a mental health episode.”

Last year, the number dipped to 123, likely a result of pandemic restrictions that kept many housed Angelenos from interacting with those who are experiencing homelessness.

People experiencing homelessness and suffering from mental illness who were a victim of crime, 2017-2020

Mel Tillekeratne, co-founder and executive director of Shower of Hope, which provides shower services to individuals experiencing homelessness, believes the numbers are actually higher. He said that people who are homeless are completely exposed to crime.

“We get to go home and close the door and lock it, but for people on the streets, someone can rip a tent open and be assaulted,” said Tillekeratne, who spent nearly eight years working on Skid Row.

[Get COVID-19, crime and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

From Jan. 1-May 31, 19 people experiencing homelessness and also suffering from mental health issues were a victim of crime in Downtown, representing 59% of the total incidents. Downtown includes the community of Skid Row.

In nearly 19% of the reported crimes, a victim was robbed. People suffering from mental health issues and also experiencing homelessness were assaulted (sometimes with a deadly weapon) in more than half of the incidents this year.

It is unclear precisely how pervasive mental health issues are among the population of people experiencing homelessness. The 2020 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count, conducted by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, reported that 26% of unsheltered individuals suffered from a long-term mental illness. However, a Los Angeles Times analysis of the previous year’s LAHSA data found that 51% of people living on the streets suffered from mental illness. The tally includes those with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Tillekeratne said during his time working on Skid Row, the most vulnerable population was women who were being assaulted and trafficked. According to LAPD data, during the first five months of the year, there were 19 female victims of crime citywide who were suffering from mental health issues and experiencing homelessness. Two of them reported being raped, according to the LAPD.

Tillekeratne added that people suffering from mental illness are often not taken seriously. He recalled encountering a woman who performed sex work on Skid Row.

“She came up to me one day crying, the left side of her face was bruised, and admitted she was assaulted and raped by two individuals,” he said. “I wanted her to report it to the police, but she started laughing at me and asked, ‘Do you know what would happen to me if I call 911?’”

Addressing the root causes

In April, during his State of the City speech, Mayor Eric Garcetti proposed removing police from addressing mental health issues that do not involve crime. He announced plans to deploy Therapeutic Unarmed Response for Neighborhoods van units that will “dispatch mental health workers to some 911 calls for emergency assistance with nonviolent situations.”

Last week, during a media session as part of a meeting of the Big City Mayors group, Garcetti said that 90% of the funding for the TURN vans comes from the county. However, he said that without flexible income streams, other services could be hampered.

“We can’t help pay for those drivers, put them in our fire stations, pay the 911 operators to figure out you don’t have to send a police officer,” he said in response to a Crosstown question, adding that funding for social workers and substance abuse programs is also at risk.

The Brain and Behavior Research Foundation found that homelessness can be a “traumatic event that influences symptoms of mental illness” and can lead to “higher levels of psychiatric distress.”

Those higher levels of distress are why Tillekeratne said he started Shower of Hope. He believes the services help restore self-confidence and are a “fresh start” for people to begin piecing their lives back together.

“When homeless individuals are aware of how they smell, how bad they look, and are not happy with the way they feel about themselves, they tend to isolate, which increases stress and mental health issues,” said Tillekeratne, who is seeking additional funding for his organization through the LA2050 grant competition. “This also means they are likely to be more targeted for crime since criminals know they are easy targets.”

How we did it: We examined crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from Jan. 1, 2010-May 31, 2021. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.