Girding for a high-rise housing battle

Los Angeles is at the tail end of a massive seven-year building boom that allowed for a record number of new residential units. Now, it’s about to embark on another one that could be more than three times as large.

But hold the applause for now. The city is still unlikely to make much of a dent in the twin crises of rising housing costs and homelessness.

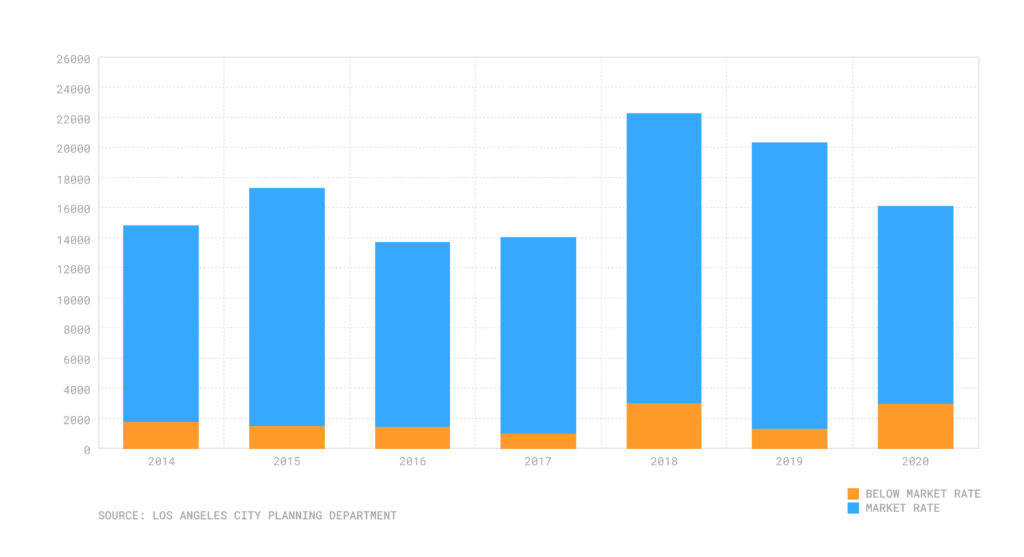

Between 2014 and 2020, the city permitted 117,000 residential units. That far outstrips the goal of 82,000 units that had been laid out in what is known as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment, or RHNA. (The cycle concludes this October.)

[Get COVID-19, crime and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

Those targets are set by the Southern California Association of Governments, or SCAG, in order to meet statewide goals for new housing creation. (The targets only establish how much housing has been permitted for construction, not how many units are completed. That number is often considerably lower.)

The high point in the recent cycle was 2018, when 20,831 units were permitted. Last year, the figure dropped to 16,089, as the pandemic slowed the process.

Housing units permitted in Los Angeles, 2014-2020

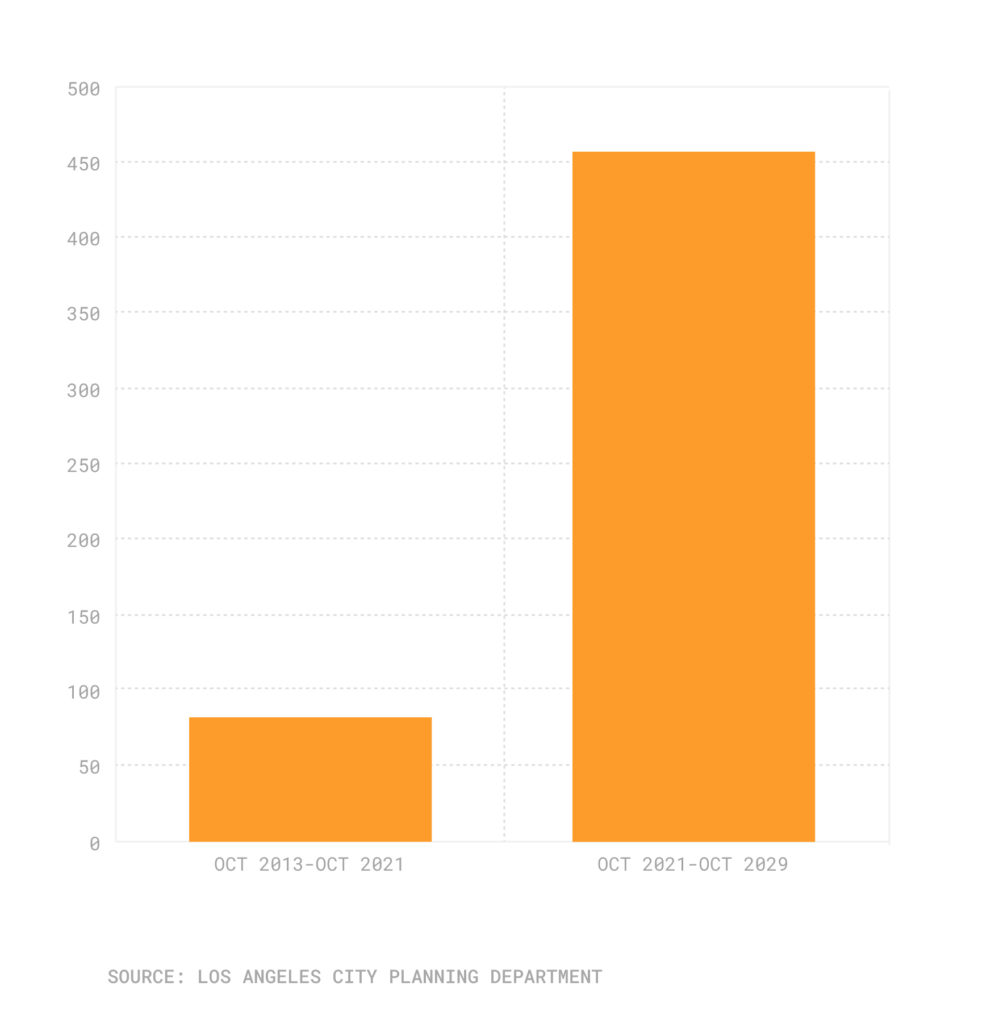

During the next cycle, which ends in 2029, the city of Los Angeles has committed to permit more than 456,000 new units.

If even partially successful, it’s likely that the city will be denser and taller, with vast areas rezoned for more and bigger construction. And the growth could encroach on one of the signature elements of L.A. living—the single-family home.

“We need to reconsider the city’s attitude toward growth,” said Matthew Glesne, who leads the housing policy unit in Los Angeles’s Department of City Planning. “We’re putting single-family housing on the table.”

The housing hangover

The massive increase in projected construction is an attempt to make up for years of mismanaging housing needs in the region. Previously, in calculating RHNA targets, the state would estimate expected future population growth, then determine how many additional units would be needed. However, during the 1980s and ’90s, when the region added millions of residents, building fell far short of demand. That left a lingering housing deficit that was never addressed in RHNA targets.

With the next cycle, the region aims both to anticipate future growth while also making up for the massive shortfall accumulated in previous decades.

Los Angeles housing unit minimum goals in Regional Housing Needs Assessment cycles

In addition, SCAG had historically placed much of the burden for creating new housing in the Inland Empire, where land is cheaper. That accelerated urban sprawl, tangled commutes and reduced air quality. This time around, SCAG is trying to reorient new housing in coastal areas, leading to higher targets in places such as Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and Culver City.

In the most recent cycle, the city of Los Angeles was tasked with permitting 20% of the region’s new homes. In the next cycle its share is 34%.

Meeting those numbers will require a remapping of many neighborhoods. Currently, 70% of the land zoned for housing is reserved for single-family homes. That means the Planning Department will need to rewrite zoning rules to allow for more multi-unit apartment complexes and even high-rises.

“What’s in our capacity is zoning, creating more opportunities of where housing can be built,” said Glesne.

Still, no one anticipates that Los Angeles will come close to creating the required number of low-income housing units. Of the 117,000 units permitted in the last cycle, 11% were classified as below market rate. For example, in 2019, permits were granted for 19,002 market-rate units, but just 1,327 below-market residences.

In the coming round, 57% of the 456,000 units are supposed to be accessible for low-income residents, a goal widely seen as unattainable.

“The deck is stacked against affordable housing,” said Glesne, noting that there simply isn’t enough public money to subsidize that many units.

Not everyone agrees that policies promoting below-market rate housing end up delivering on their goal. Mott Smith spent years developing affordable and middle-income housing and is now chief executive of Amped Kitchens, a commercial kitchen complex developer and operator.

“Affordable housing is a seductive distraction,” he said. “It’s the worst way to make housing affordable.”

Subsidized housing has to clear numerous bureaucratic and financial hurdles, and projects end up taking much longer to complete.

“We’re talking about programs that are adding a couple of thousand units a year. You don’t need a math degree to understand it’s not working,” said Smith.

NIMBY

The radical rezoning of Los Angeles for bigger multi-unit apartment blocks and fewer single-family homes is expected to spark a conflict. Many local groups have long resisted any changes that would alter the fabric of their neighborhood by allowing for greater population density. The powerful Sherman Oaks Homeowners Association has fought against development projects in the San Fernando Valley for years, and is girding for battle against the city.

“We believe that there are enough zoned apartment areas to build a tremendous amount of housing, and the state and city do not need to destroy single-family neighborhoods,” said the group’s president, Richard Close.

He notes that so much of the housing created recently is at the top end of the scale. “Building a $5,000-a-month apartment does not in any way help with the homeless crisis,” he said. Instead, Close argues that the city and state should use surplus budget funds to build housing specifically for homeless individuals.

YIMBY

Other civic groups are lobbying for the type of changes that the Sherman Oaks Homeowners Association is trying to block. During the 2013-2021 RHNA cycle, Culver City added only 92 housing units, less than half of its target. That prompted some local residents to band together to create Culver City for More Homes.

“We are a community that has looked the same for quite some time— higher income, more white—which correlates to a resistance to change,” said one of the founders, Elias Platte-Bermeo.

They canvassed their neighbors and lobbied city officials to make a case for changes to the city’s approach to planning that would allow for building more apartment complexes. In May, they convinced the city council to agree to put the issue on the table.

Want to know more about where you live? Check out the Crosstown neighborhood map or send us an email at askus@xtown.la.