Los Angeles hits a high for drug overdose deaths

Early on a Saturday morning in September, police and paramedics rushed to a call at a home in Venice. They came upon a tragic scene: Three men were dead, and a woman was rushed to the hospital. All of them had overdosed after using cocaine laced with the highly potent synthetic drug fentanyl. One of the deceased was comedian Fuquan Johnson.

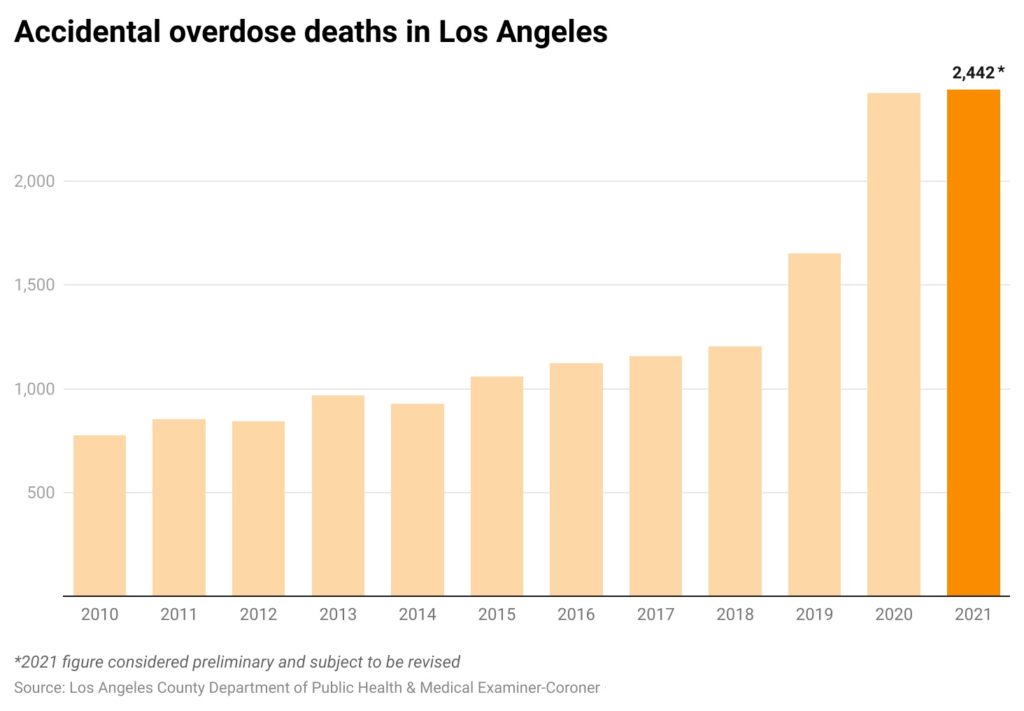

The deaths were tragic and alarming, but also frustratingly common: In 2021, a total of 2,442 people in Los Angeles County died from a toxic drug supply. (The tally is not yet final, and is expected to change.)

This marked the seventh consecutive year that overdose deaths increased in the county, and the toll is the highest ever recorded, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. It is also more than double the 1,059 overdose deaths recorded in 2015.

Beyond the rising death toll are other troublesome trends: Illicit drug deaths are more frequently impacting Black, Hispanic and Native American communities, and people experiencing homelessness are dying far more often than in the past.

Those working on the front lines of the crisis have seen plenty of death. What makes this moment different is that it is not just young people or novices experimenting with narcotics who are dying. Increasingly, longtime drug users, who have built up a level of tolerance, are succumbing.

“We are seeing more and more people who have been using opioids and other drugs for a very long time, die,” said Shannon Knox, the director of education and training at the Los Angeles Community Health Project, an organization that provides harm reduction services to people who use drugs. “Where they used to be able to manage, they’re dying now.”

[Get COVID-19, crime and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

In 2021, the non-profit reversed 4,520 overdoses by administering naloxone to drug users. Naloxone, which is sold under the brand Narcan, helps a patient suffering an opioid overdose. According to the National Institutes of Health, when given via an injection or nasal spray, it attaches to opioid receptors and blocks opioid effects. If someone has stopped breathing, naloxone can quickly restore normal functions.

Knox said she expects the number of overdose reversals to rise this year.

Worsening crisis

Fatalities spiked after the onset of the pandemic. News reports have been filled with stories of lives cut short.

Experts describe the overdose crisis in waves. The first wave occurred in the 1990s, when drug companies ramped up efforts to convince doctors to provide opiates, which led to overprescribing. The second wave began in 2010 with rapid increases in overdose deaths due to heroin. The third wave was attributed to illicitly manufactured fentanyl. This wave, experts say, was initiated by dealers who seized an opportunity to make more money by cutting heroin and other drugs with fentanyl, which is cheap to produce.

The problem is potency. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, fentanyl is 100 times stronger than morphine and up to 50 times stronger than heroin. The CDC estimates that 106,854 people died of an illicit drug death in the 12-month period ending in November 2021. In the calendar year of 2019, there were 72,151 overdose deaths, according to the CDC.

Certain deaths draw outsized attention and remind the public of the dangers of a tainted drug supply. Such was the case with Johnson in the Venice home, and the overdose of rapper Mac Miller, who died in Studio City in 2018 after taking counterfeit oxycodone pills laced with fentanyl. Last week Ryan Reavis was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison for his role in helping supply the pills to Miller.

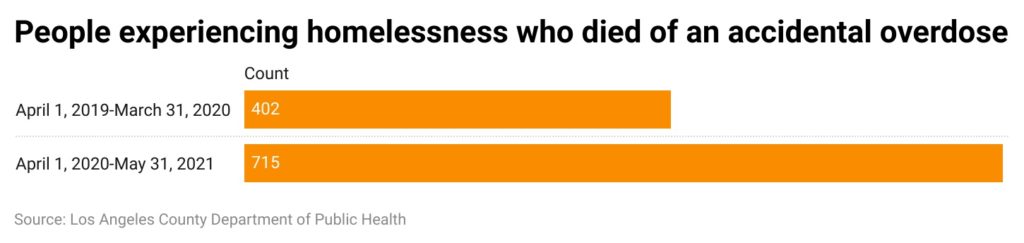

Although it does not draw the same level of attention, the crisis is severely impacting people experiencing homelessness. A new report from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health found that overdoses were the leading cause of death for unhoused people from April 1, 2019-March 31, 2020, and again in the following 12-month period, when the impacts of COVID-19 were being felt. The report notes that during the pre-pandemic year, 1,271 people experiencing homelessness died of all causes. In the following year there were 1,988 fatalities, a 56% increase.

The report found that 402 people experiencing homelessness died of a drug overdose in the pre-pandemic year. But from April 1, 2020-March 31, 2021, the number of unhoused people who died from an accidental overdose spiked 78%, to 715 fatalities. That was more than twice the toll due to the second leading cause of death—309 people experiencing homelessness died of coronary heart disease.

From April 1, 2020-March 31, 2021, according to the report, 179 people experiencing homelessness in L.A. County died of COVID-19.

Impacted communities

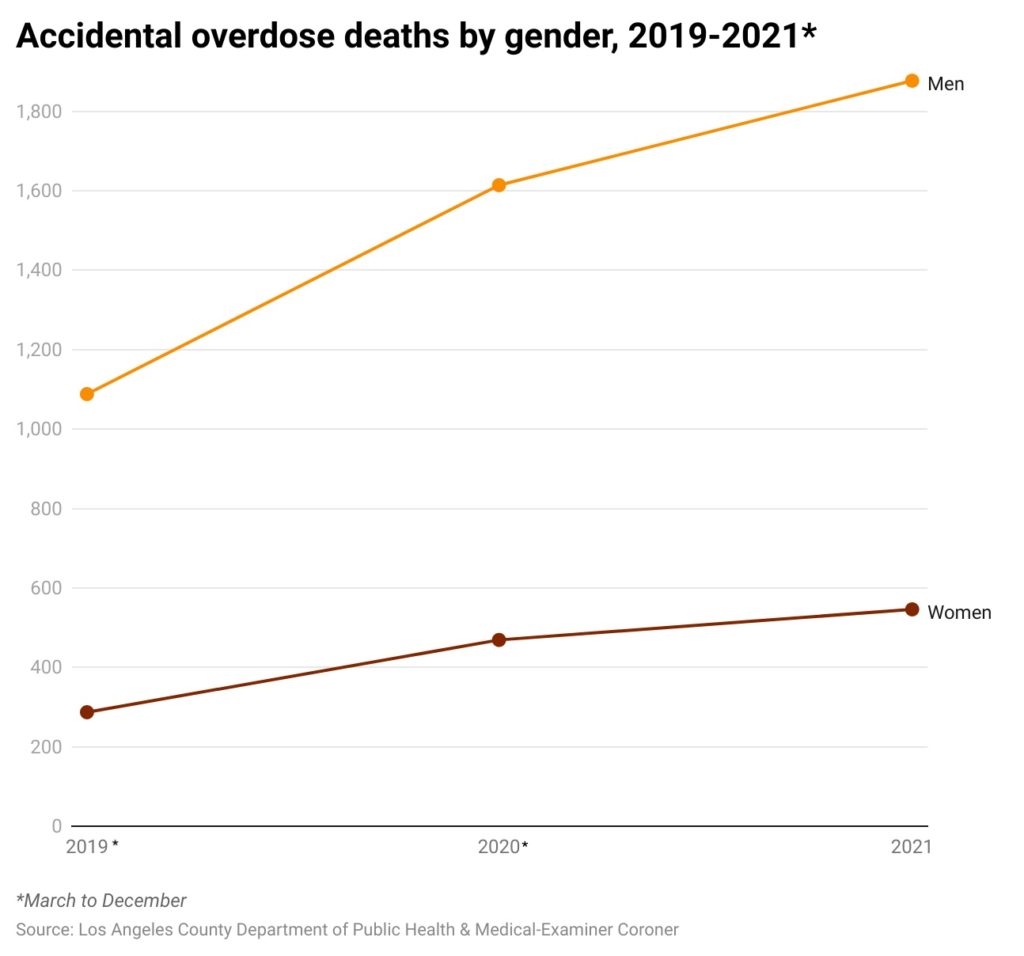

Men have historically died of drug overdoses at a higher rate than women, and that has continued in the current crisis. A report published last July by the County Department of Public Health found that from March-December of 2019, 1,088 men died, compared with 287 women. In the same period in 2020, there were 1,614 male deaths, versus 469 women.

For 2021, the average age of death of an overdose victim was 42.7, according to the Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner.

Joseph Friedman, an addiction researcher at UCLA, co-authored a national study which found that in 2020, Black people had a fatal overdose rate of 36.8 per 100,000 residents. That was an increase from 24.7 the previous year. American Indian or Alaskan Natives experienced the highest rate of overdose mortality in 2020, at 41.4 per 100,000.

By comparison, the overdose mortality rate for white Americans in 2020 was 31.6 per 100,000 residents, and the rate for Hispanics was 17.3 per 100,000. The year 2020 marked the first time since 1999 that the overdose death rate for Black Americans surpassed that of white individuals.

“The overdose crisis is becoming a racial justice issue,” Friedman said in an interview.

Friedman said overdose rates in California were flat for a long period of time, even as they were spiking in many parts of the country. There has been a shift in the past five to seven years as the crisis evolved from a rural to an urban one, he said.

“Some of this is California catching up to the rest of the country, but unfortunately, it looks like they’re kind of overtaking other parts of the country that have historically had higher overdose rates,” he said.

Sarah Ardalani, a spokesperson for the County Coroner, said the office is preparing for a possible continued increase in drug-related deaths, particularly with fentanyl.

“We have made personnel hires as budgets allow,” Ardalani said in an email.

Overlapping Factors

In 2021, the most commonly found narcotic in drug-related deaths in Los Angeles County was methamphetamine, followed by fentanyl, according to the Coroner’s office. Ricky Bluthenthal, a sociologist and professor in the Department of Population and Public Health Sciences at the USC Keck School of Medicine, said this is because of people using multiple substances.

“A lot of that, I suspect, has to do with people who are increasingly unhoused and people are using [drugs]. Some of the meth use is instrumental,” Bluthenthal said. “You need to stay awake at night so you won’t be attacked or have your things stolen, that kind of reasoning.”

Bluthenthal has worked in this space since the ’90s, when he helped start a syringe exchange program in Oakland during the HIV/AIDS crisis. He thinks public health officials should respond more aggressively to the rising overdose death toll. That has happened in certain places. San Francisco Mayor London Breed in December declared a state of emergency in the Tenderloin district due in part to rising overdose deaths. The government of British Columbia did the same when overdose deaths spiked in 2016.

Last month, President Biden called for more federal funding to address the nation’s overdose and addiction crisis.

Bluthenthal said it makes sense for politicians in Los Angeles to step up as well.

“There is a lack of urgency that comes to the issue,” he said.

Bluthenthal said the homelessness crisis, with more than 60,000 unhoused people in the county, ties into the challenge.

“We need to be more comprehensive in our response. We need to do a lot more harm reduction. But we also need to do a lot more housing,” he said. “We have to take a more humanistic approach to trying to help the humans that find themselves unhoused and using substances.”

If someone is using drugs on their own, they can call the Never Use Alone hotline. Through this service, an operator stays on the line and will call 911 if the person becomes unresponsive.

How we did it: We examined data from the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner-Coroner and the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health from Jan. 1, 2010-Dec. 31, 2021.

Interested in our data or have additional questions? Email us at askus@xtown.la.