Marijuana legalization only widened the racial divide in policing

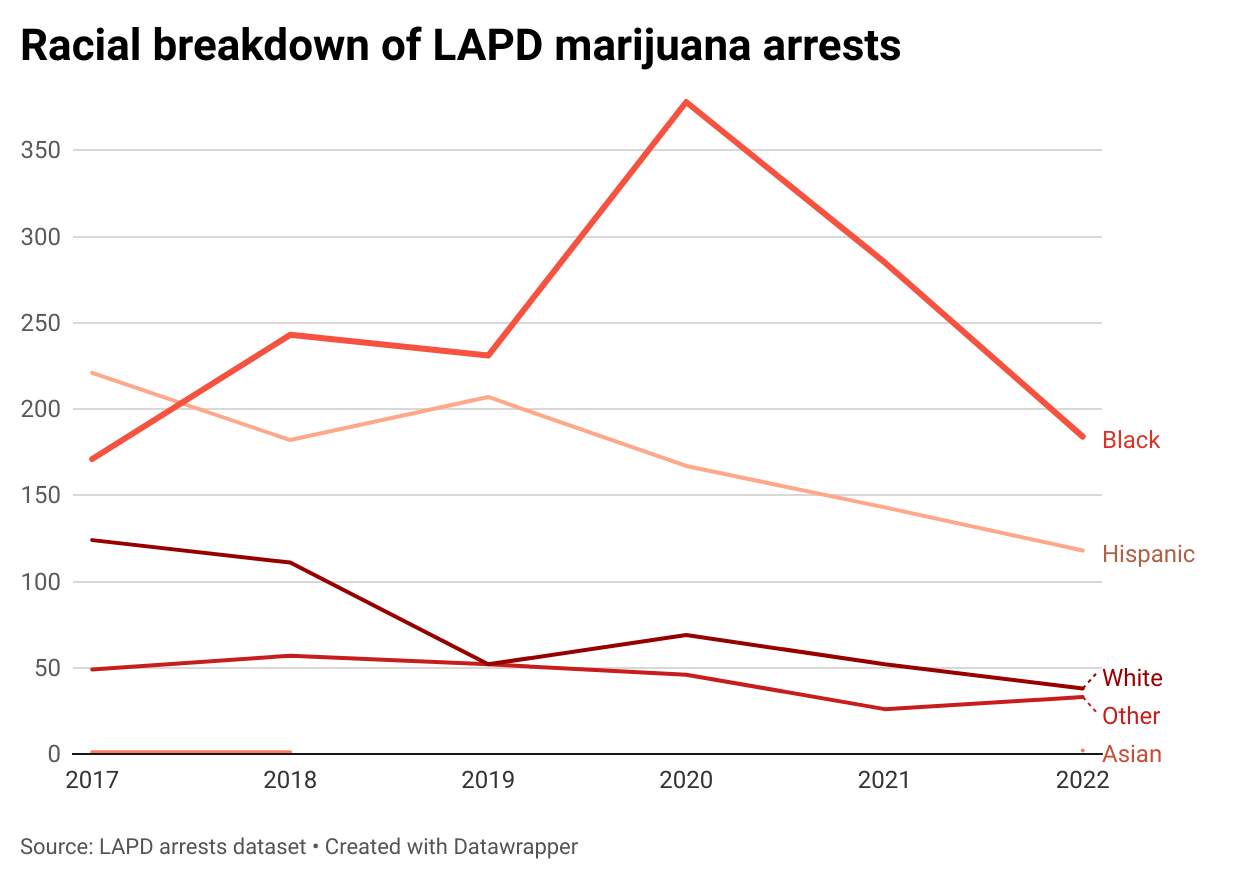

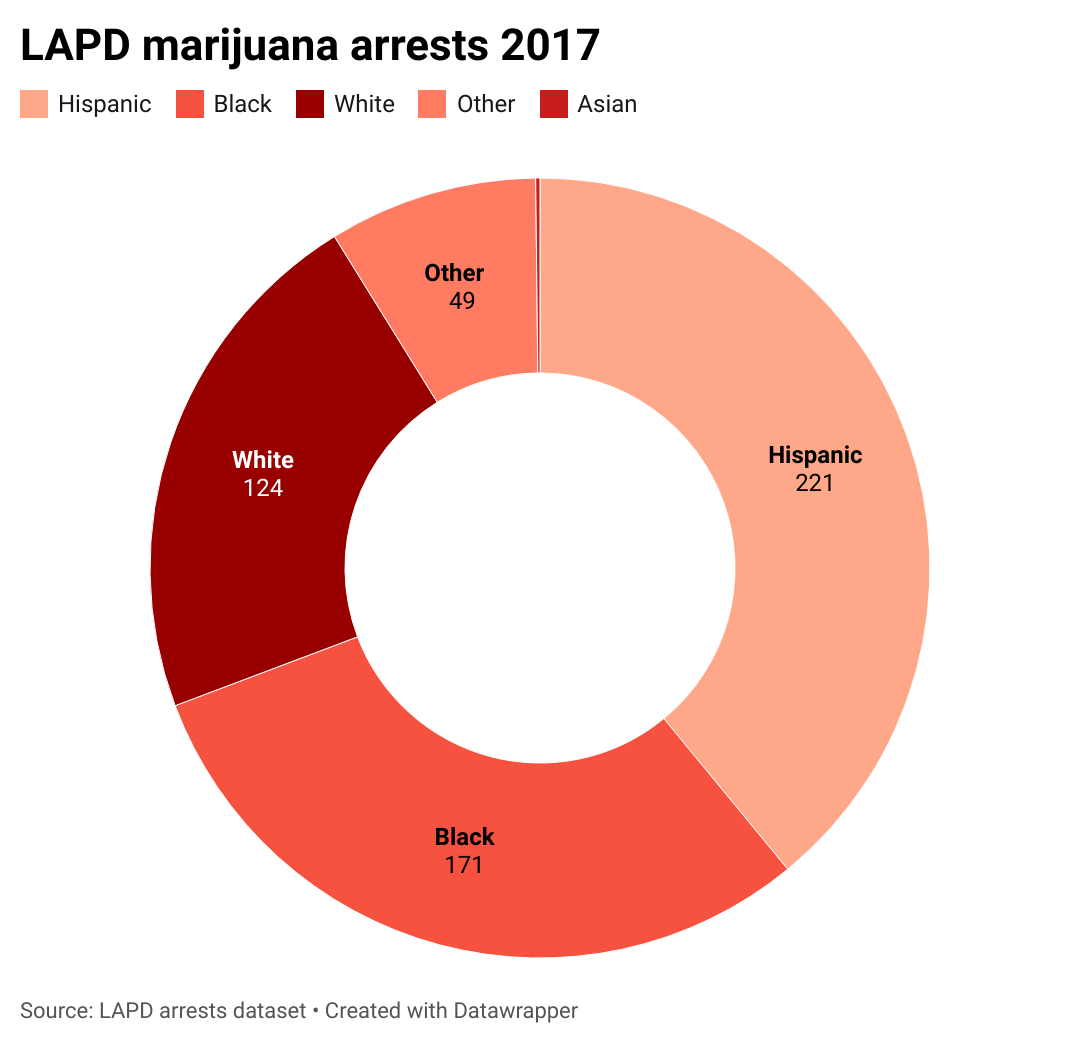

In 2017, the last year that recreational cannabis was illegal in California, the Los Angeles Police Department arrested 566 people for marijuana-related crimes. Black people accounted for 30% of those arrests. They make up about 8% of the city’s population.

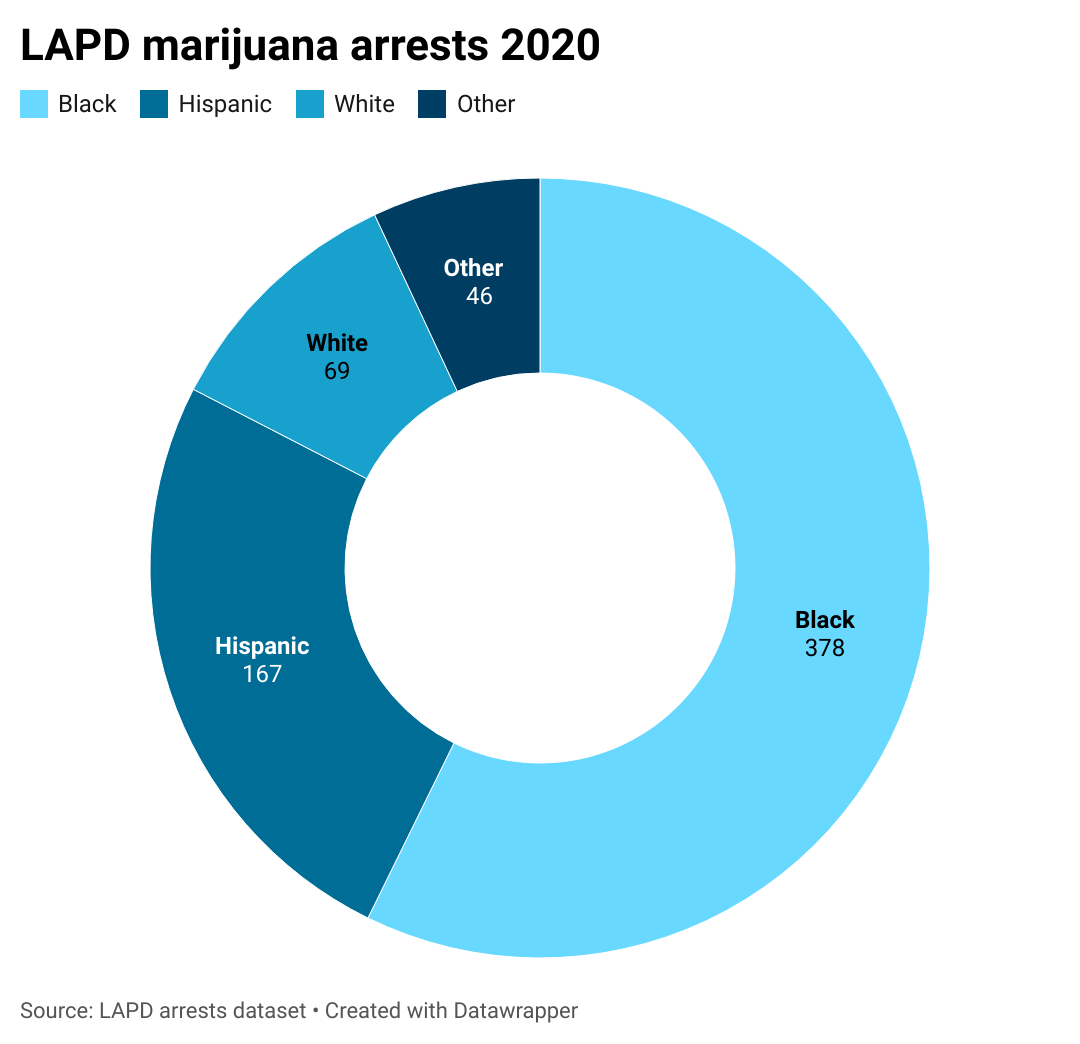

In 2020, with legal marijuana businesses popping up everywhere—and illegal ones still operating with impunity—cannabis-related arrests fell for white and Hispanic people in the city. But arrests of Black people shot up. That year, 378 Black people were arrested for pot, according to publicly available LAPD data. That represented 56% of all marijuana arrests in the city.

Legalization, which took effect in 2018, was seen, among other things, as a step to redress historic inequities. The country’s decades-long war on drugs had disproportionately targeted Black communities. Decriminalizing marijuana was supposed to offer the twin benefits of reducing patterns of over-policing while offering opportunities for economic advancement in the newly legal business.

[Get crime, housing and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

But in Los Angeles, at least, the opposite happened.

“The legalization of it never changes the bias that is so entrenched in our system,” said Elizabeth Lashley-Haynes of the Racial Justice Unit of the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office. Since marijuana became legal for recreational use, she said, “My colleagues and I noticed that it seems to be that the lingering marijuana charges are mostly Black clients.”

An LAPD spokesperson, in an email, declined to comment.

Long march toward legalization

California’s journey to legalization began in 1996, when the state became the first in the nation to allow marijuana use for medicinal purposes. Proposition 64, passed by voters in 2016, legalized recreational sale and personal use by those over 21. That went into effect on Jan. 1, 2018. Legal marijuana was seen as a civil rights issue, and both the California branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the American Civil Liberties Union supported it.

Legalization discussions were accompanied by promises of equity programs that would promote minority business ownership. The city sought to be on the frontlines. Mayor Eric Garcetti authorized the creation of the Department of Cannabis Regulation, and in 2019, Imani Brown was appointed director of its Social Equity Program. (The department’s work is separate from the LAPD.)

“Cannabis criminalization and its enforcement has had long-term, adverse impacts, particularly for low-income and minority community members for decades,” said Brown.

There were also efforts to provide avenues for expungement for those convicted of marijuana-related offenses. The 2018 bill AB1793 required the state’s Department of Justice to review such convictions dating back to 1975.

The state has made progress on this front, though more than 30,000 convictions remain on the books.

Many believe those promises have never been met. They include Keith Humphreys, a professor of psychology at Stanford University and an expert on addiction. Humphreys served on the ACLU’s Blue Ribbon Panel on Marijuana Legalization in California, which was formed in 2013. The panel was chaired by then-Lt. Government Gavin Newsom, and was intended to draft a framework for a legal marijuana policy in the state. But Humphreys soured on the way legalization took shape.

“The biggest forces behind legalization were focused on making money,” said Humphreys. “They invoked racial justice as a deep and abiding concern, but they didn’t actually believe it. The second they got the ability to make lots of cash, their interest in creating a global society disappeared.”

In Los Angeles, Brandon L. Wyatt, a board member of the Minority Cannabis Business Association, believes the city failed to acknowledge the longstanding financial and structural issues in the cannabis industry. He pointed out that the majority of licensed marijuana dispensaries are on the wealthier Westside of the city or in the San Fernando Valley. Many fewer are located in historically Black areas.

“The first legal frameworks that were created were targeted to prefer white rich males,” said Wyatt, who is also the co-founder of BCB Mastermind, an executive training program for cannabis business owners of minority backgrounds.

Arrested at LAX

One of the most frequent locations for marijuana-related offenses is Los Angeles International Airport. As with the city as a whole, there is a racial disparity in airport arrests. Last year, according to police data, there were 103 marijuana-related arrests at LAX, representing 28% of the total in the city. Seventy-two of those arrested, or 77%, were Black. Studies have shown that marijuana usage is roughly similar for both Black and white individuals.

Lt. Karla Rodriguez of Los Angeles Airport Police pointed out that there is a discrepancy between state law and what is allowed on the federal level. Many people learn that the hard way.

“There is a misconception that it is acceptable to travel with cannabis since it is legal in California,” said Rodriguez. “However, there are federal travel restrictions, which prohibit traveling with cannabis, regardless of the amount.”

Rodriguez said she was unable to comment on the racial disparity in arrests, saying, “We do not maintain those records.”

Outside of Westchester, where LAX is located, most neighborhoods in Los Angeles only saw one or two marijuana arrests last year—if any. But there are a few neighborhoods that stand out. Broadway-Manchester, in South Los Angeles, recorded 48. Hollywood counted 36 and Watts, also in South Los Angeles, had 21.

In those three neighborhoods, there were 53 Black people and 48 Hispanic people arrested, together accounting for 96% of the total, according to police data. The bulk of those arrests were for the charge of possession for sale. In 2022, 40% of all marijuana arrests in the city were for that charge. The second most common reason for a marijuana arrest last year was transportation , at 34%. Possessing or transporting over 28.5 grams of marijuana can still qualify as a crime.

There has been widespread criticism of the way California implemented legalization. Tax revenue from sales has fallen short of expectations and an illegal market still thrives. Critics blame the red tape involved with running a state-approved marijuana business and the fact that there are generally light punishments for those who skirt the system entirely.

The taint of an arrest

Even in the era of legal recreational use, a marijuana arrest can exact a heavy toll. In 2020, Santa Monica resident Arthur Colwart had an acquaintance who ran unlicensed pop-up marijuana dispensaries. The person asked Colwart if he would hold a cardboard box to collect a $5 entrance fee for a dispensary operating in Downtown Los Angeles. He agreed. Soon after arriving, he recalled, six police officers showed up to shut it down. He said he and two other people were arrested.

Colwart, who is 69, said he was sent to two different holding cells and spent hours with one arm handcuffed in an uncomfortable position to a bench in a police station. He believes this is what later necessitated rotator-cuff surgery.

The experience was jarring. “You get one phone call,” he recalled. “I had to call my wife. I am stressed out. She’s stressed out.”

Colwart said he had two court appearances over the next two years, and that at one point there was a bench warrant out for his arrest for non-appearance. Though the charges were eventually dropped, the effects lingered.

Lashley-Hayes, of the public defender’s office, said that a marijuana arrest, even without a conviction, can cause problems for years.

“Even a small marijuana charge makes someone ineligible for federal student aid,” she said. “So we have clients who can no longer go to college because they have a stupid minor drug charge.”

Gabriel Kahn contributed to this report.

How we did it: We analyzed seven years of arrest data from the LAPD, examining 44 different charges related to marijuana, as well as the descent of those arrested.

Questions about our data or want to reach out? Contact us at askus@xtown.la.