Restraining order violations are rising in Los Angeles. Advocates say that’s a good thing

On Aug. 16, 2023, a 60-year-old woman in Wilmington called 911 to report an abuser had violated a restraining order. A 19-year-old Sun Valley woman reported a violation at her home. A 56-year old man called in a violation at an apartment complex in El Sereno.

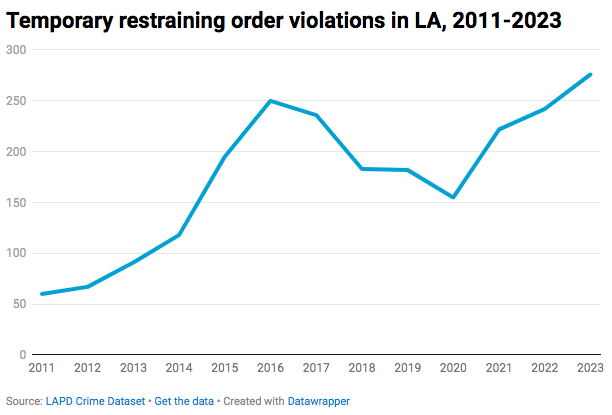

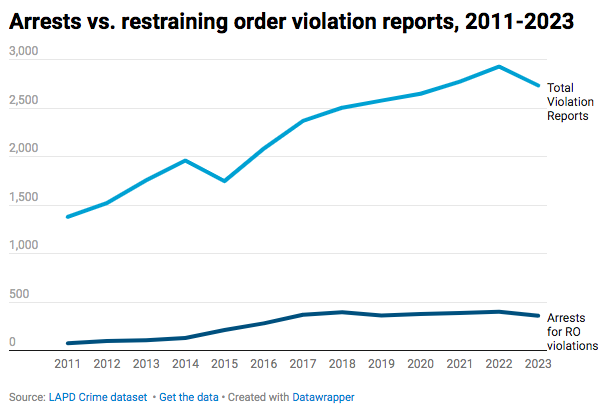

These incidents in far-flung neighborhoods were three of 266 such reports made during the month of August. By the end of 2023, there had been 2,736 reports of restraining order violations, according to publicly available Los Angeles Police Department data. Although that is in line with the 2022 count, it is approximately double the number of restraining order violations recorded in the city in 2011.

Los Angeles courts grant thousands of restraining orders every year. It is one tool to protect victims from domestic violence, allowing authorities to intervene and prevent physical, sexual, mental or emotional abuse. It requires the person to stop all harassment and stay away from the victim—their home, workplace and their children. Violations can result in arrest, fines and up to a year in jail.

While there are ongoing problems with LAPD enforcement—sometimes with tragic consequences—advocates encourage victims to obtain an order, document and report each violation by an abuser.

The spike in reports may raise eyebrows, but experts in the field see a positive in the form of more victims being willing to speak up.

“I think a lot of the advocacy that has happened within the last decade or so is paying off,” said Alyson Messenger, managing staff attorney with the Jenesse Center, a domestic violence intervention and prevention non-profit in South L.A. The organization runs a free legal aid clinic in the Inglewood courthouse, which includes helping victims file restraining orders.

“We now have a better educated bench who understands domestic violence,” she added, meaning judges and courts. “As a result, survivors are actually getting their orders of protection.”

[Get crime, housing and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

At the onset of the pandemic, there were worries that shelter-at-home orders would lead to many instances of domestic violence or other abuse going unreported. Yet even with limits on local court proceedings in 2020, the number of restraining order violation reports trended upward.

Messenger said when courts reopened and continued to allow remote access, it was beneficial for survivors, letting them Zoom into hearings without having to face their abuser.

She said advocates emphasize reporting all restraining order violations, which also may help explain the increase. This allows enforcement action to be taken.

“That means documenting every violation and reporting it to law enforcement, however minor it might seem,” Messenger said, “Because in our experience, the violations typically do start off very minor, but then they escalate in severity.”

Anatomy of a restraining order

There are several types of restraining orders: In the face of violence or threats, an Emergency Protective Order can be requested by a responding police officer, and if approved by a judge is valid for seven days. A Temporary Restraining Order lasts 21 days, and can be applied for at the court—reported violations of those orders are also on the rise.

To take effect, the named person must be served with the order and a notice of a court hearing date. At the hearing, a judge will allow both parties to explain the situation. The judge determines whether the restraining order will expire or grant it for five years.

There can be logistical issues in serving the order, said Det. Marie Sadanaga, an LAPD domestic violence coordinator. “We can’t say that [an abuser] knowingly violated the order if they haven’t been served,” she said.

If that is the case, and the abuser is on scene, responding officers will serve the order then.

Sadanaga credits more public awareness and domestic violence advocates for making the process more accessible. The paperwork can be daunting, but there’s support.

“All of our courthouses in L.A. County do have restraining order clinics,” she said. “So if someone does go into a family courthouse to get a restraining order, and isn’t totally sure or just overwhelmed by what to do, and how to get help, there are people there that can help walk them through the process.”

Neighborhood trends

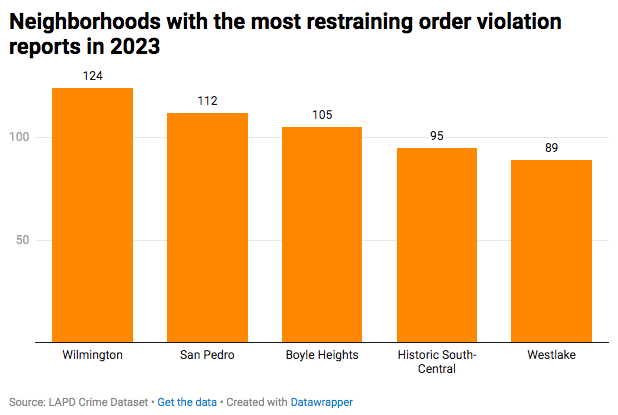

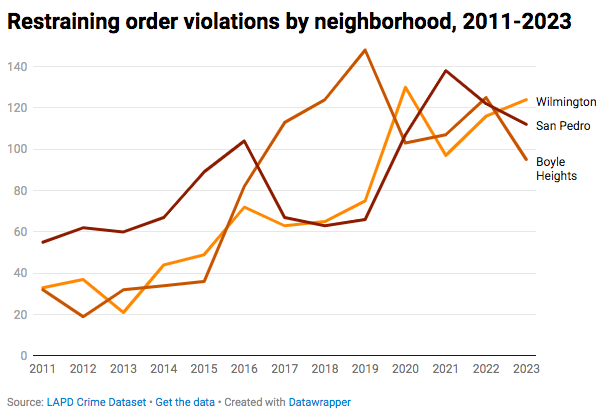

There are reports of restraining order violations all across Los Angeles. Yet since 2011, the greatest number of reports have been in neighborhoods in the harbor area. That was the case last year, with 124 incidents in Wilmington and 112 in San Pedro.

Sadanaga said elevated numbers in the waterfront area may be tied to higher rates of gun violence in those communities. Studies also show that these neighborhoods have high rates of income inequality, toxic pollution and health issues associated with port operations.

Additionally, Sadanaga noted that there is a family court in San Pedro. “The access to a court to go in and get restraining orders could also increase the number in the area,” she said.

There has been some large year-to-year variance in certain neighborhoods. For example, the numbers of violations in Boyle Heights rose rapidly from 2015 through 2019, then dropped. Meanwhile, reports in Wilmington have risen each of the past two years.

Since 2011, 88% of the victims in restraining order violation reports were female, with just 12% being male. According to police data, over the past decade 60% of victims were identified as Hispanic, while 20% were Black and 14% were white. The majority of victims are under 40.

Enforcement is a complex picture

What makes a restraining order more than just a piece of paper is enforcement. When a violation is reported, the police response depends on the level of danger, according to Sadanaga. If the abuser is physically present and threatening the victim, that means lights and sirens, she said.

“If the restrained person is at the scene, then it’s a mandatory arrest,” she said.

Despite the increase in restraining order violation reports in recent years, the number of LAPD arrests of abusers has risen marginally. Last year, police made 364 arrests for the seven most common restraining order violations, including stalking. Advocates say the number of arrests compared with the number of violation reports shows sporadic enforcement, and reflects the need for law enforcement to take these calls seriously.

Sadanaga said the discrepancy is likely due to many victims making delayed reports, and often coming into the station after the crime occurred.

“That is often the case that by the time law enforcement gets there, the perpetrator is gone,” agreed Messenger of the Jenesse Center.

She added that the matter can be complicated by the victim not having a working address for the abuser, or the threat being made by phone or social media.

Sadanaga acknowledged that in misdemeanor cases, police will not immediately head out to arrest someone. However, she said a crime report will be taken and police will attempt to find the individual.

“We do an investigation and submit it to the City Attorney for filing consideration,” Sadanaga said. “If a case is filed, an arrest warrant will be issued for the suspect.”

Path to prosecution

Pallavi Dhawan is the director of domestic violence policy with the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office, which is tasked with filing charges for violating a restraining order. She said that in some cases, such as a suspect driving by a person’s home or sending letters, police and prosecutors may record a “technical violation,” but without a credible threat of violence it doesn’t lead to arrest or prosecution.

She acknowledges this leads to frustrations about the process, and can pose difficulties for victims.

“There’s definitely room for improvement on how these cases are handled, both at the level of law enforcement response, and then at the level of filing by the prosecuting agency,” Dhawan said.

Still, Dhawan agrees increased access to restraining orders and reporting violations is impactful. She says one area of progress is public awareness and recognition around types of domestic violence. She pointed to a 2021 state law that expanded the definition of coercive control and abuse, identifying new areas where a restraining order can be sought.

“Like isolating a person from their sources of support, depriving them of basic necessities, controlling, monitoring, regulating their movements,” she said.

Still, she acknowledges that the real effectiveness of a restraining order varies. Some offenders who have gone through a legal process will think twice before doing anything, knowing the potential consequences. Others will not be deterred. That is why she advocates for heightened reporting and enforcement action.

“The more that you can add these potential consequences, and you’re sending the message that people are taking it seriously, I think the deterrence effect is greater,” she said.

Sadanaga agrees that public awareness and advocacy matter. There is help for the victim, and a message is sent to the abuser that people are paying attention.

“Restraining orders do help,” Sadanaga said. “It almost puts a person on notice, too. Like, hey, now we know about it, and others are aware of your actions. And if you do anything else, there are additional consequences.”

If you or someone you know is in need of support, here are some resources: The National Domestic Violence Hotline is a free, confidential service providing support in over 200 languages for survivors of domestic violence. Call (800) 799-7233, or text “START” to 88788.

For support in obtaining a restraining order in Los Angeles: the Jenesse Center runs a free, confidential hotline at (800) 479-7328.

How we did it: We examined publicly available crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from Jan. 1, 2010–Dec. 31, 2023.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Have questions about our data or want to know more? Write to us at askus@xtown.la.