When stalkers come to your doorstep

If a stalker knows where you live, or worse, follows you home, it is hard to feel safe in your own home.

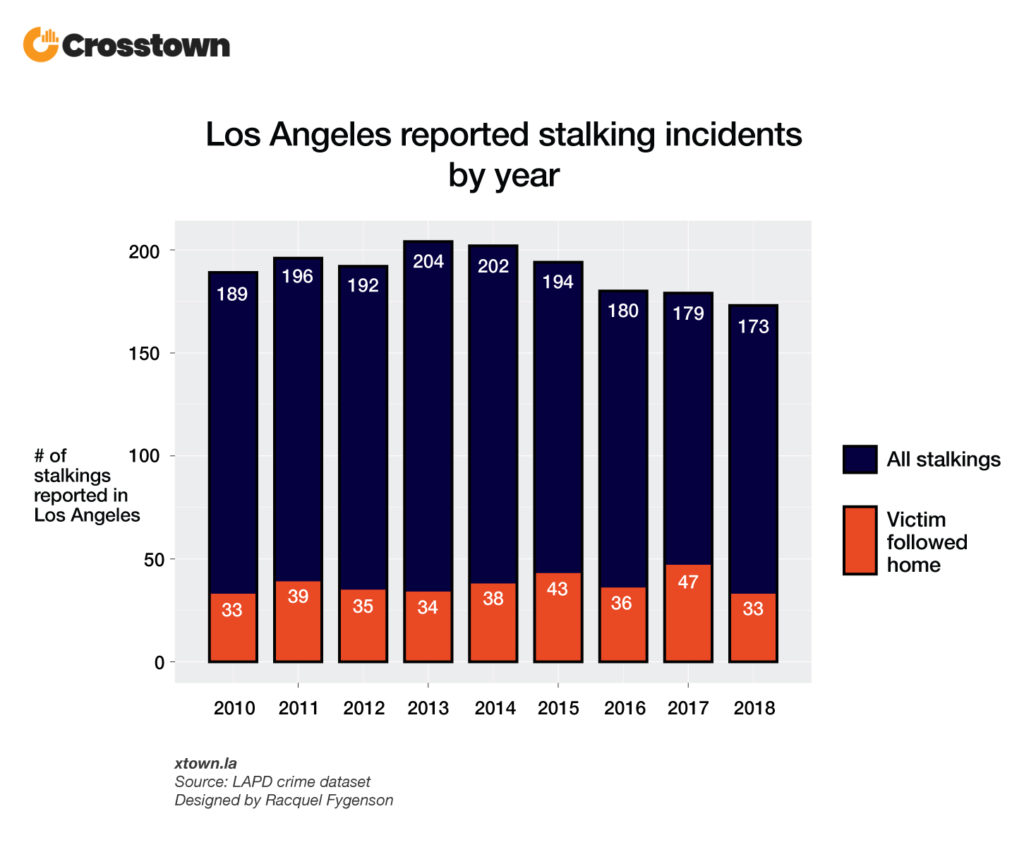

Unfortunately, that was the case for one out every five people who were stalked in Los Angeles over the past nine years. They were followed home by a suspect, on foot, by bicycle, by car.

This piece is the second story on stalking, and the third installment in a new Crosstown weekly feature, where we look at crimes that don’t always get attention because the reported numbers are relatively low. They may be uncommon, they may have fallen under the radar, they may even seem a little weird. But they’re important and interesting and we’re here to cover them. Here is our first story on stalking, in which looked at the location of reported stalking crimes and what, if any, weapons were used in the crimes.

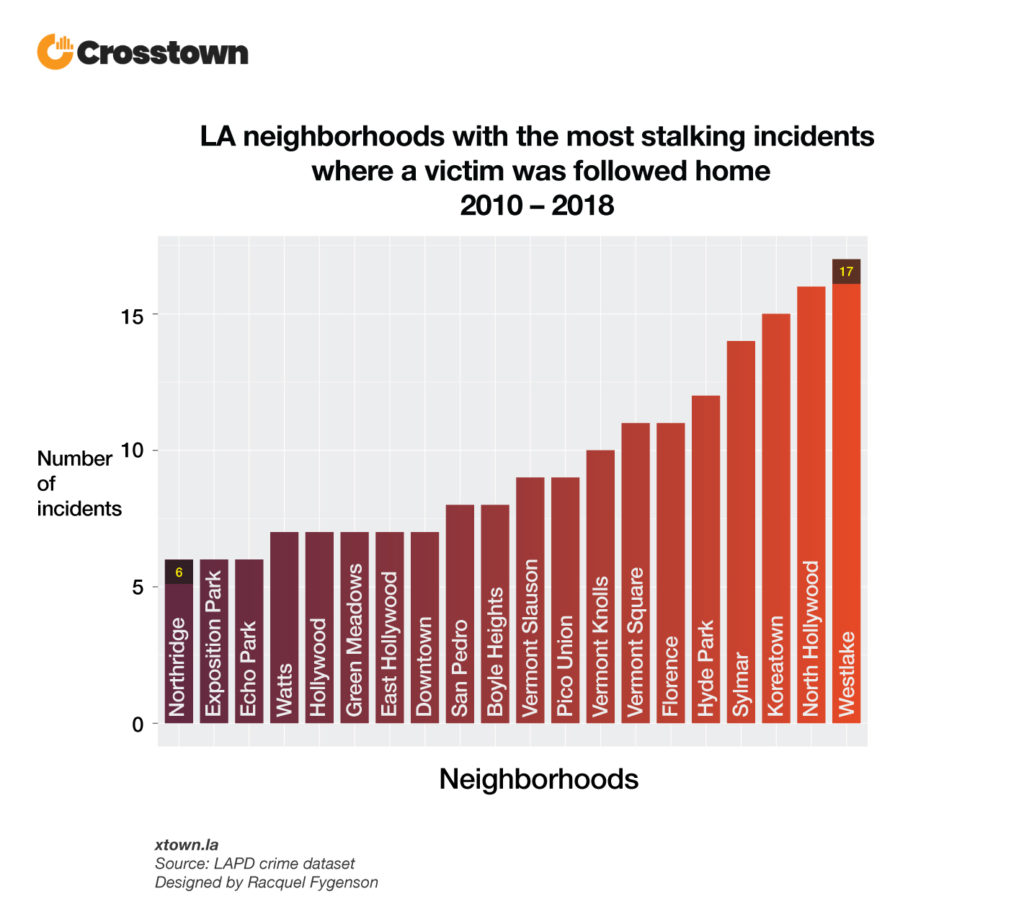

The neighborhood in which the most number of reporting stalking incidents occurred from 2010 to 2018 was Westlake, with 17 incidents. Next on the list was North Hollywood, with 16 cases, Koreatown with 15 and Sylmar with 14.

Among the top 20 neighborhoods for all reported stalking incidents over the past nine years, every neighborhood had at least six cases where the suspect followed the victim home.

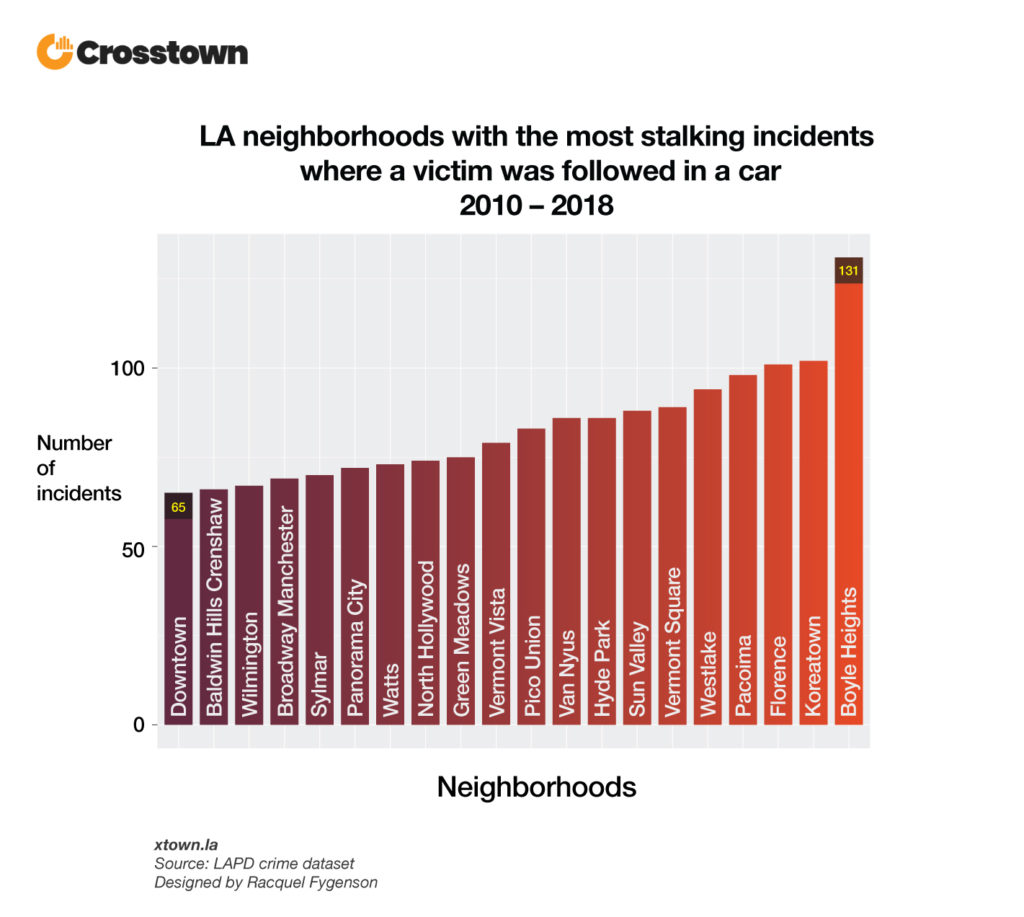

Stalking can happen in any number of ways. In fact in Los Angeles, a city of cars, the total number of cases where a stalker followed a victim in their car from 2010 to 2018 was 3,408.

The suspects in these cases followed the victims in their cars wherever the victim happened to be going. (This could, of course, include following a victim home as well, meaning an overlap in our datasets.)

Over the past nine years, the top five neighborhoods where the suspect followed the victim in a car had more than 90 incidents each.

And then there’s stalking on the Internet, which can feel just as scary as any other stalking incident.

In the City of Los Angeles, cyberstalking peaked in 2016, with 30 reported incidents, according to the LAPD.

In California, cyberstalking is stalking that takes place via an “electronic communication device.” This could include stalking via the Internet, email, text messages, phone, video or even a fax machine. California stalking laws make it illegal for someone to harass or threaten another person to the point where that individual fears for their safety or the safety of their family.

On Jan. 22 2019, the FBI arrested a Brandon Fleury of Santa Ana, Calif., for accusations that he was using Instagram to harass the relatives and friends of the victims in the Parkland school shooting.

He allegedly tagged multiple people in his posts, captioning them with messages like “Your grief is my joy,” “I gave them no mercy,” and “I killed your loved ones hahaha.”

Fleury admitted to FBI detectives that he created the Instagram profiles so that he could “troll” the victims, spark reactions and gain popularity.

If you are being cyberstalked, you should take the following actions, according to the National White Collar Crime Center:

- Send the person one clear, written warning not to contact you again.

- If they contact you again after you’ve told them not to, do not respond.

- Print out copies of evidence such as emails or screenshots from your phone. Keep a record of the stalking and any contact with police.

- Report the stalker to the authority in charge of the site or service where the stalker contacted you. For example, if someone is stalking you through Facebook, report them to Facebook.

- If the stalking continues, get help from the police. You also can contact a domestic violence shelter and the National Center for Victims of Crime Helpline.

Here are some resources for victims of stalking:

- National Domestic Violence Hotline: 800-799-7233

How we did it: We examined publicly available LAPD data on reports of stalking from Jan. 1, 2010 (the earliest available data) – Dec. 31, 2018. For neighborhood boundaries, we rely on the borders defined by the Los Angeles Times. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.