This election brought a boom in hate crimes

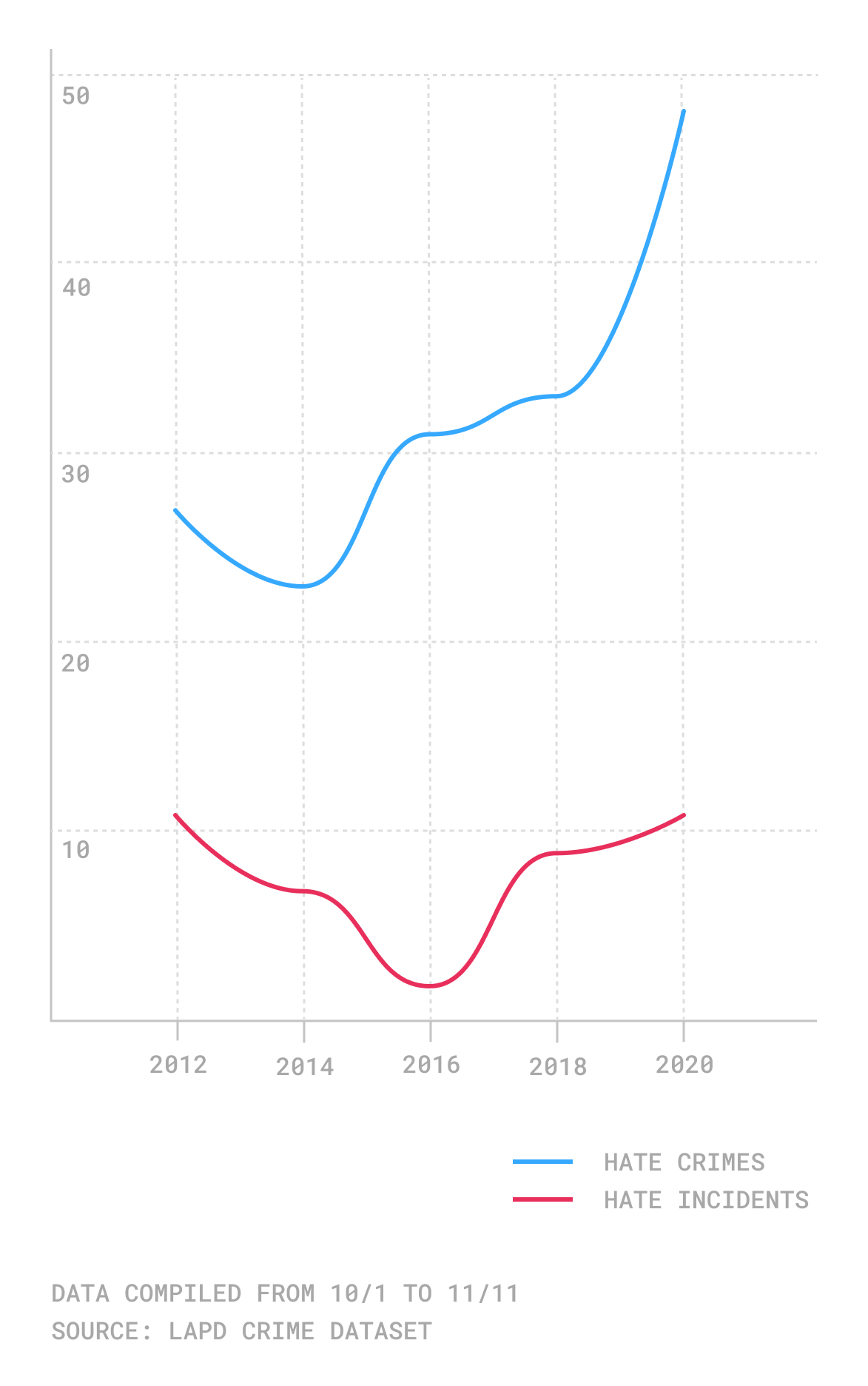

In a six-week period leading up to and shortly after the 2020 presidential election, the number of reported hate crimes in the City of Los Angeles soared. According to the Los Angeles Police Department data, there were 48 hate crimes reported between Oct. 1-Nov. 11, a 45% boost from the 33 recorded in the same time period during the 2018 midterm elections.

Experts have warned that hate crimes can increase around elections, but in Los Angeles, this most recent campaign season pushed that violence to new heights.

“In political seasons, we often see some not-too-nice exchanges,” said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “When it looks like there will be a flip nationally in some way, like red to blue, there seems to be an increase that accelerates more in the run-up.”

The number of hate crimes committed in the City of Los Angeles has increased in each presidential or midterm election cycle since 2012, when there were 27 hate crimes reported in the six-week period. In 2016, there were 31 reports.

Hate crimes and hate incidents in LA in the run-up to elections

This year’s rise in hate crimes coincided with a presidential campaign in which President Donald Trump stoked racial divisions in the country. During a September debate with the now President-elect Joe Biden, Trump refused to condemn white supremacy, and urged members of the far-right group the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by.”

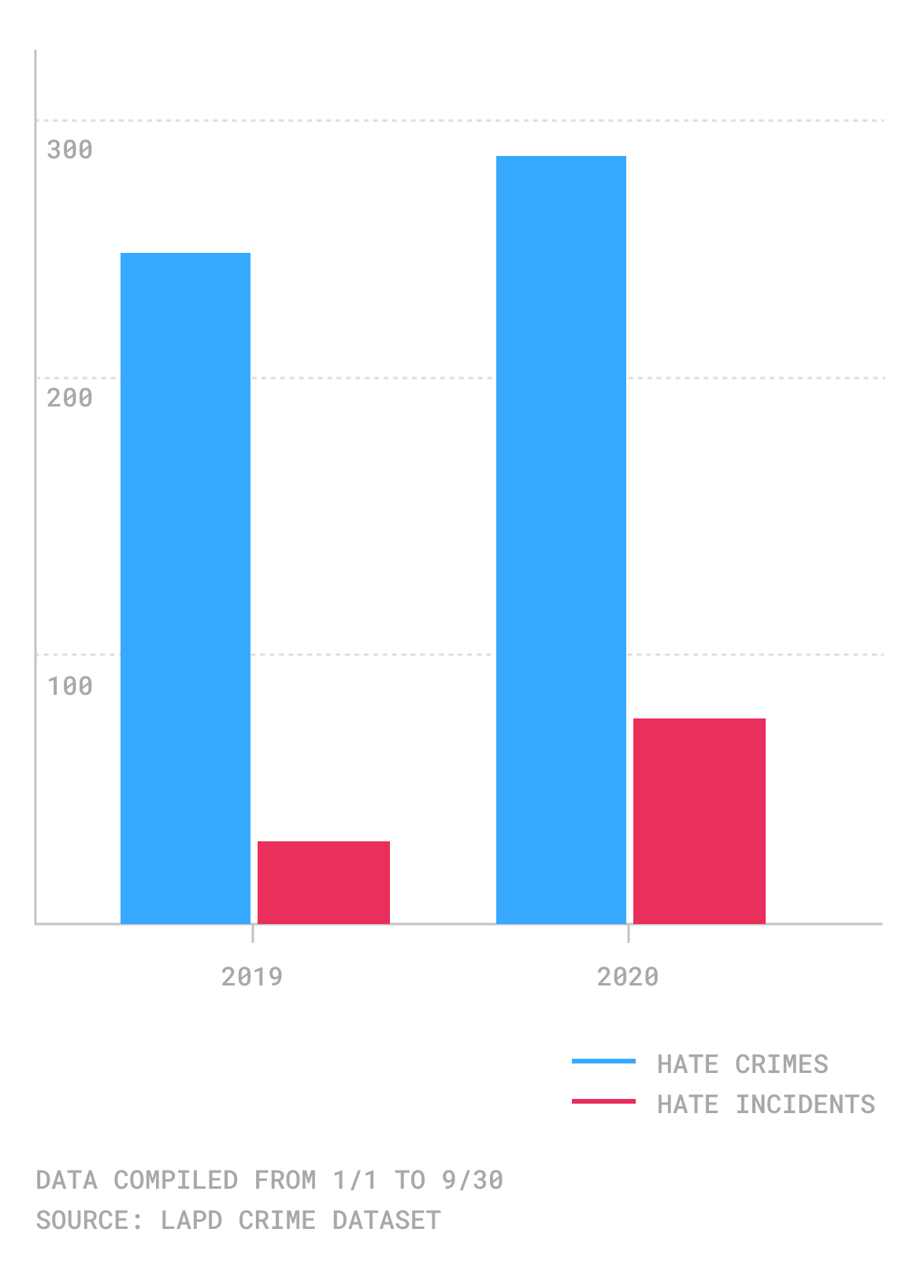

The number of hate crimes overall in Los Angeles has also been rising steadily since 2014. In less than 11 months this year, the city has already recorded 335 hate crimes, surpassing the record 326 reported for all of 2019. However, the number of actual crimes is likely far higher. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that less than half of all hate crimes are reported to the police. One reason is that many victims do not trust that members of law enforcement will do much about it.

Black people were disproportionately the victims, being targeted in 25% of those hate crimes, despite representing just 8.9% of the city’s population. Hispanic people, who make up nearly half of the city’s residents, accounted for 31% of the victims.

The LAPD defines a hate crime as “any criminal act or attempted criminal act directed against a person or persons based on the victim’s actual or perceived race, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, disability or gender.” These are separate from “hate incidents,” which generally include instances of abuse stemming from racial, gender or sexual-orientation bias, but do not result in a formal crime report.

Hate incidents also increased in Los Angeles this election cycle, with 11 reported cases from Oct. 1-Nov. 11, outpacing the nine from the same period in 2018 and the two in 2016.

Hate crimes and hate incidents in 2020 vs. 2019

Political hate crimes, too

Levin, director for the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, said that, nationwide, threats are expanding to include political hate crimes. He cited an increase in threats against public officials and pointed to the FBI’s October arrest of more than a dozen individuals for plotting to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

“There is an overlay taking place in 2020 that amplifies the risk of hate crime but also redirects it,” said Levin. “Some people who wanted to beat up a Jewish person last year now want to beat up someone supportive of health regulations.”

During testimony to the House Committee on Homeland Security last year, Levin said that November 2016 was “the worst month in 14 years,” with 758 hate crimes reported to the FBI across the country. National figures for 2020 are not yet available.

Levin testified that data showed the majority of murders committed in 2018 by white supremacists overwhelmingly occurred just before the midterm elections.

Levin also told the committee that internet platforms are “force multipliers” that disseminate graphic violence with extreme views that are “disturbingly common in the general population.” These, he added, can lead to “leaderless resistance” violence that is inspired by “racist folklore.”

Looking forward to 2021

In an effort to address the situation, the LAPDrecently started tracking the types of prejudice that motivate suspects to target their victims. The department has also installed a dedicated hate-crime coordinator.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has a Hate Crime Rapid Response Team with people who are experts at handling civil rights matters.

Levin, however, said it is the office of the president of the United States that has the greatest influence on curtailing hate crimes. He noted that when Trump in 2017 issued an executive order barring foreign nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States, there was a double-digit increase in attacks against Muslims the following week.

Conversely, when Trump condemned intolerance against Asian Americans this past March, in the wake of the spread of COVID-19, which originated in Wuhan, China, data showed a decrease in anti-Asian hate incidents. Trump later undermined his own condemnation – and sparked outrage – when he referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus” or the “kung flu.”

In his testimony to the House last year, Levin suggested a federal overhaul of statutes such as enhancing provisions to counter the growing threat against public officials and people who hold elected office, as well as increased funding to combat far-right extremism.

How we did it: We examined publicly available crime data from the Los Angeles Police Department from Oct. 1-Nov.11 between 2012 – 2020. Learn more about our data here.

LAPD data only reflects crimes that are reported to the department, not how many crimes actually occurred. In making our calculations, we rely on the data the LAPD makes publicly available. LAPD may update past crime reports with new information, or recategorize past reports. Those revised reports do not always automatically become part of the public database.

Want to know how your neighborhood fares? Or simply just interested in our data? Email us at askus@xtown.la.