Parking fines no longer pay the city’s bills

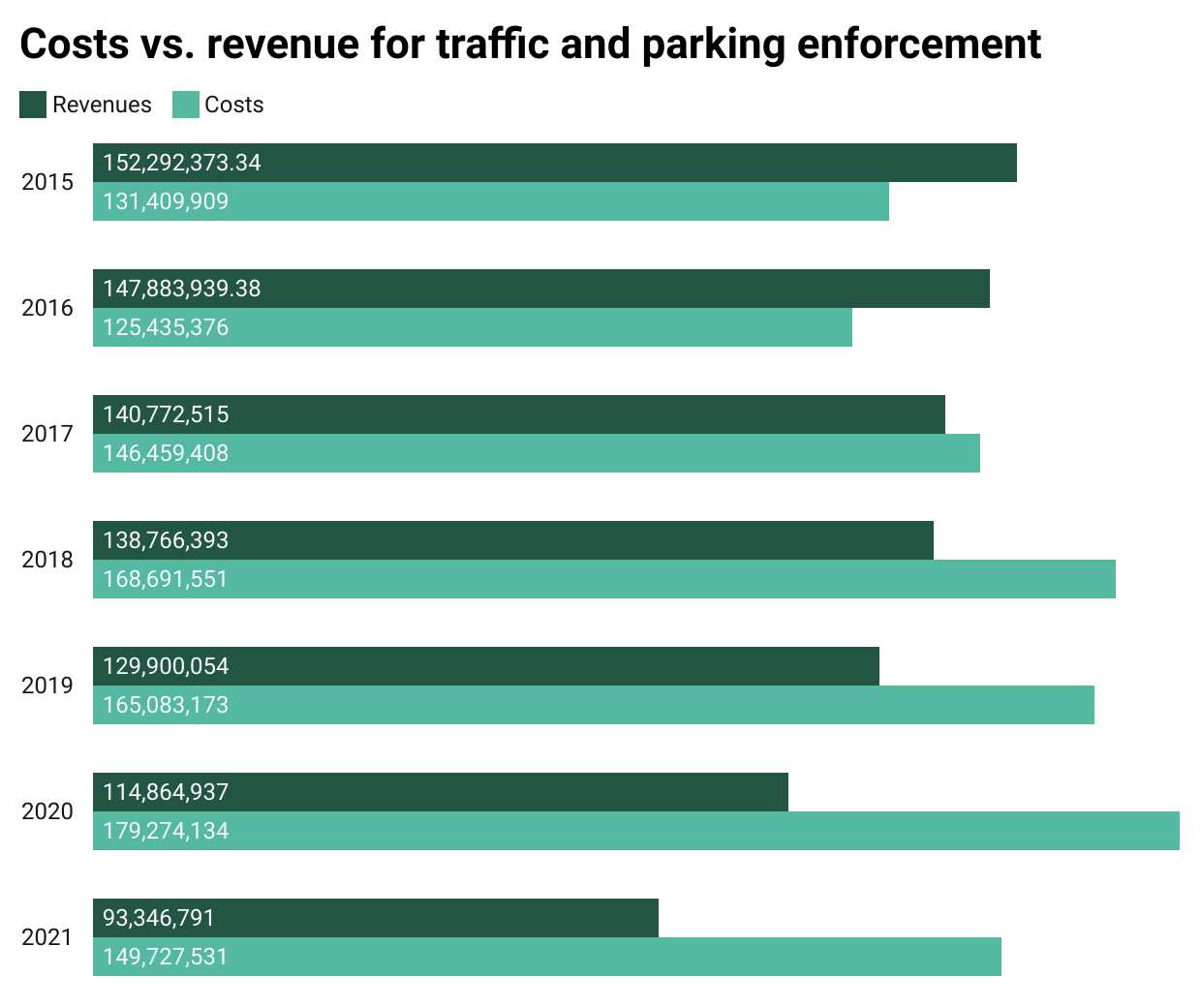

Over the past five years, fines from parking tickets have brought in over $617 million to the city of Los Angeles. But over that same time, the department in charge of writing those tickets ran up costs of more than $809 million in salaries, equipment and other expenses.

The result: Parking and traffic enforcement has cost the city $192 million more than it generated in fines.

Source: Los Angeles City Controller, Los Angeles City budget.

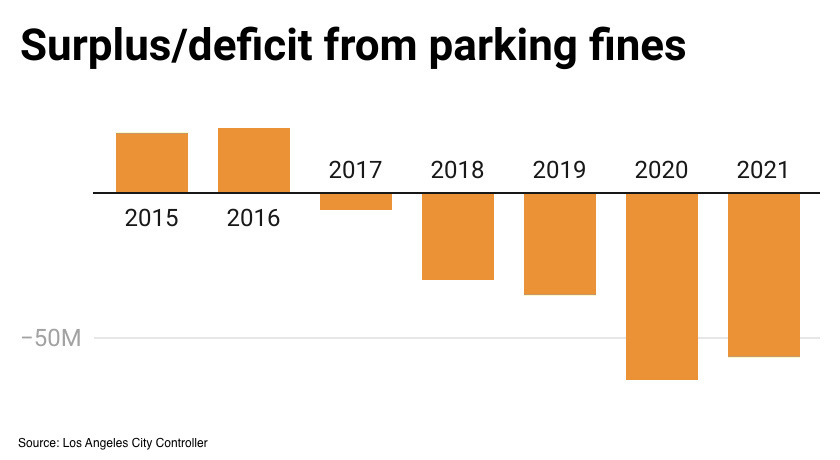

The shortfall became particularly outsized in the last two fiscal years. (The city’s fiscal year runs from July 1 of one calendar year to June 30 of the next.) In those 24 months, the parking and traffic enforcement division spent almost $121 million more than it took in through citations.

[Get COVID-19, crime and other stats about where you live with the Crosstown Neighborhood Newsletter]

A steady slide in revenue

But the gaps began to appear well before the arrival of COVID-19. In fact, parking fines were once reliably producing more than $20 million of net income for the city. That was money the city could spend on parks, youth programs, trash cleanup and more.

Yet a number of factors have conspired recently to reduce the number of tickets the city issues for expired meters or blocked fire hydrants.

Colin Sweeney, the director of information for the city’s Department of Transportation, noted that traffic officers are responsible for a lot more than just writing traffic tickets. And in recent years, those other duties have taken up an increasing portion of their time.

“Over the last decade, while revenue from citations has remained within a consistent range, our parking enforcement division has also provided a record number of traffic safety control hours for citywide projects, including street repair and maintenance, the construction and expansion of Metro Transit projects, and homeless encampment clean-ups,” he wrote in an email to Crosstown. All of those, he noted, added to the department’s costs.

The once-steady revenue stream (a typical fine is over $70) began to come unglued in 2017. That was the first year that costs outweighed ticket revenue. At the start, the deficits were small. In the budget year that ended June 30, 2017, the office had a shortfall of $5.7 million. But in the budget year that ended on June 30, 2020, the amount had grown to $64.4 million.

In the year that closed this past June 30, it was $56.4 million.

The COVID-19 crunch

The pandemic added a new wrinkle to the problem. Already, public works projects such as street repaving, were on the rise. That required the officers to spend more time directing traffic. Then, since the beginning of the pandemic, officers have had the added duties of monitoring COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites. Sweeney said that during 2020, traffic officers spent half their time on COVID-19-related work.

The most significant factor in the recent shortfall had nothing to do with staffing. During the first eight months of the pandemic, when millions of people were at home because of the closure of many businesses and workplaces, the city suspended numerous parking regulations. The number of tickets issued fell from more than 200,000 in January 2020 to approximately 45,000 three months later.

The numbers didn’t begin to pick up until October 2020. Even since then, the amount of citations written is more than 30% below pre-pandemic levels.

This is partially attributed to a staffing shortage; an estimated 22% of traffic enforcement positions are currently unfilled, according to the Department of Transportation. Although hiring efforts are ongoing, there remain more than 70 vacant positions.

The purpose of parking fines

Making money for the city is actually not supposed to be the main goal of parking tickets. “LADOT Traffic Officers’ primary mission is to ensure the safety of our roadway and support the quality of life of our communities,” Sweeney said.

Assistant City Administrative Officer Patricia Huber also emphasized that making money is not the point of the city’s parking program. “The purpose of the citation program is compliance with parking restrictions, not revenue generation,” Huber said.

Compliance is necessary for a number of reasons: first responders need space during emergencies, street sweeping has to come through and keep the city clean.

Still, some argue that the city’s budget is structured in a way that implies that parking-fine revenues are an important piece. Jay Beeber, the executive director of Safer Streets LA and past co-chair of the city’s Parking Reform Working Group, says the fact that estimated parking citation revenue is in the budget at all raises a red flag. It’s one he had brought up in the past with the working group.

“It should not be a line item in the budget, because everybody then knows what’s expected to come in,” Beeber said. “I had former officers who told us, quite clearly, they told us how all of this works on the inside and they were like ‘if you don’t come back with enough tickets, your boss talks to you and they’re like you’re not producing enough, we have a certain goal we have to meet.’ … it’s just a perverse incentive structure.”

How we did it: We examined data on city revenue for parking fines compiled by the Los Angeles City Controller and compared that against costs listed in the Los Angeles City budget.

Have questions about our data? Reach out to us at askus@xtown.la