Five charts on homelessness in Los Angeles

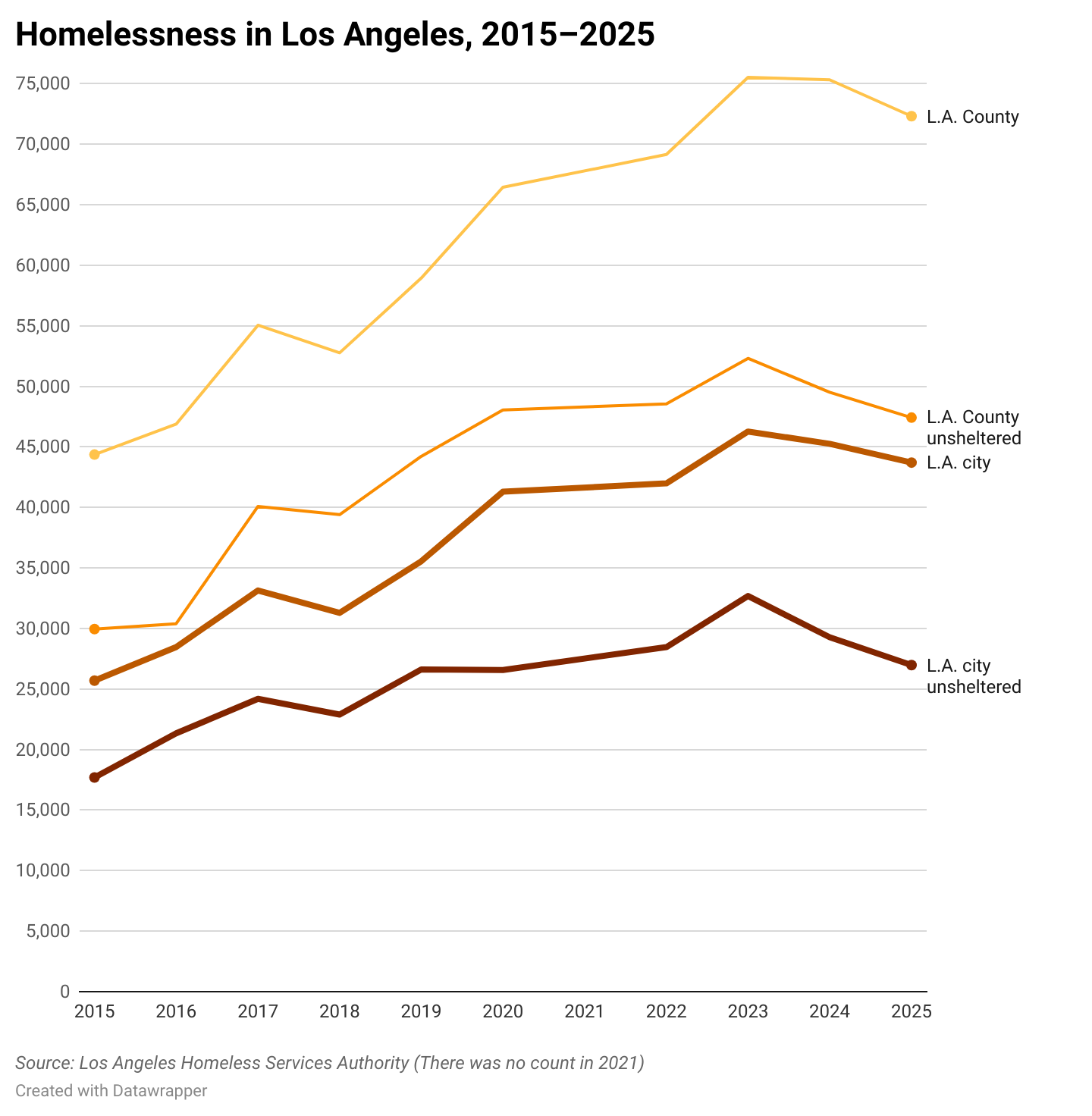

Local leaders on Monday touted the 4% drop in unhoused individuals countywide, and a 3.4% fall in the city of Los Angeles. It followed a smaller decrease in 2024, and marked the first time ever that the Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count produced two consecutive years of improvement (the count first took place in 2005).

While this represented a step in the right direction, more people are experiencing homelessness than before the pandemic. The report from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority showed that this year’s count of 72,308 unhoused individuals is 22.7% higher than the approximately 59,000 people tabulated in 2019.

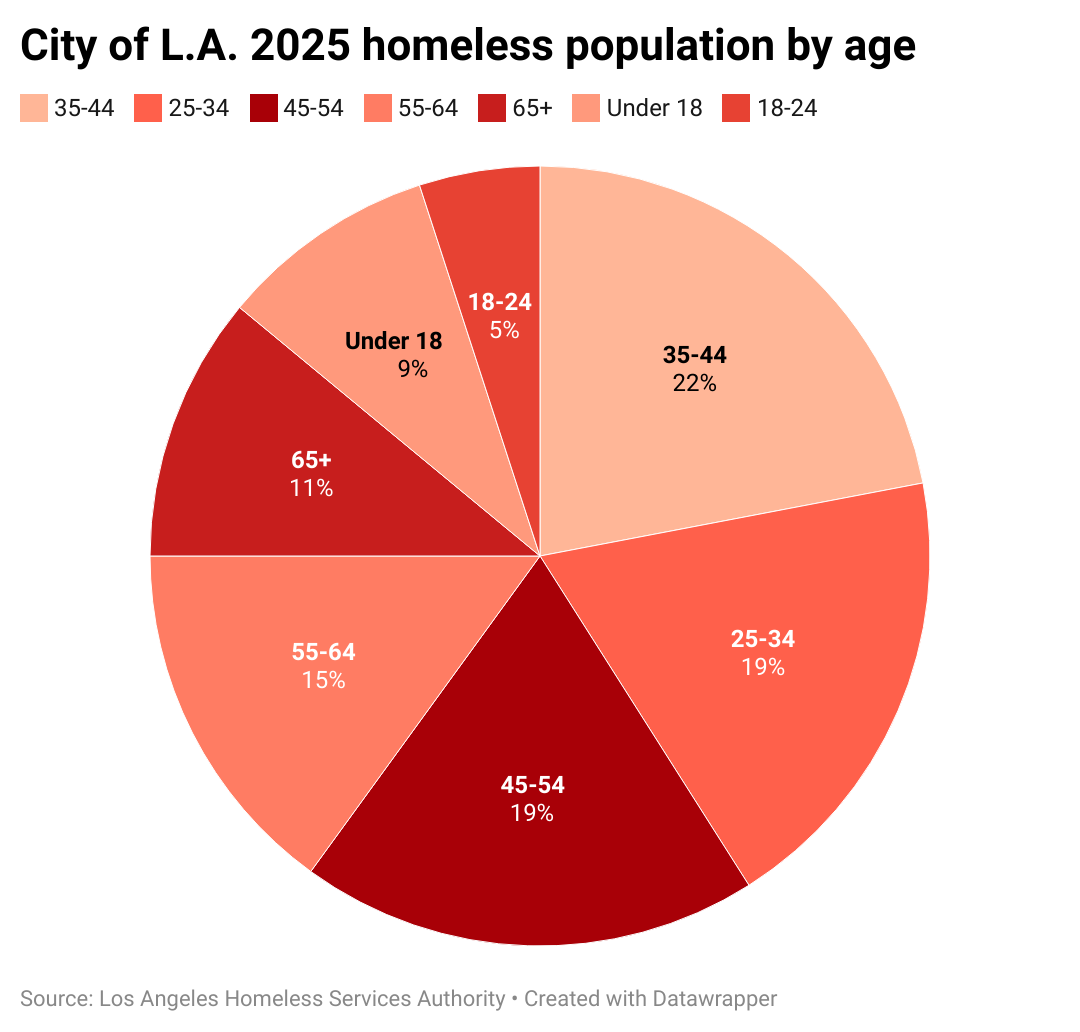

It is similar in the city. The 43,699 people experiencing homelessness this year is below the level in each of the last two years, but is 23% higher than in 2019. The homeless population is also getting older, with 26% age 55 or above.

The count was conducted over three nights in February with a process designed by the University of Southern California. Cities across the country are required to report the number of unhoused people; the figures help determine how much funding they get from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Big spending

The region has struggled with worsening homelessness for more than a decade, and annual spending from the city of Los Angeles alone is approximately $1 billion a year. While myriad tools are used to get people off the streets, perhaps the most high-profile is Inside Safe, which Bass initiated after being elected in 2022.

According to an Inside Safe dashboard, the program has removed 95 encampments, moving 4,300 people into temporary residences, with about 1,000 gaining permanent housing.

That has come at a cost. A dashboard from City Controller Kennth Mejia found that $450 million has been spent on Inside Safe—that includes hotel and motel feels, as well as real estate purchased to permanently house people.

Although Mejia’s dashboard says there have been 1,760 “program exits” from Inside Safe, the new Homeless Count did find a notable decline in what are known as “unsheltered” homeless individuals, or people living on the street or in vehicles. The approximately 47,000 in the county was down 9.5% from last year.

In the city, there were 26,972 unsheltered individuals. That is about 2,500 fewer than in 2024, and marks a 17.5% reduction from the number two years ago.

Homelessness was a key issue in the 2022 mayoral election between Bass and businessman Rick Caruso. After winning the race, Bass declared a homelessness state of emergency. She has also taken steps to streamline the construction of affordable housing in the city.

To that aim, the Homeless Count detailed a record number of “permanent housing placements” in 2024. The 27,994 is an increase of approximately 8,500 since 2019.

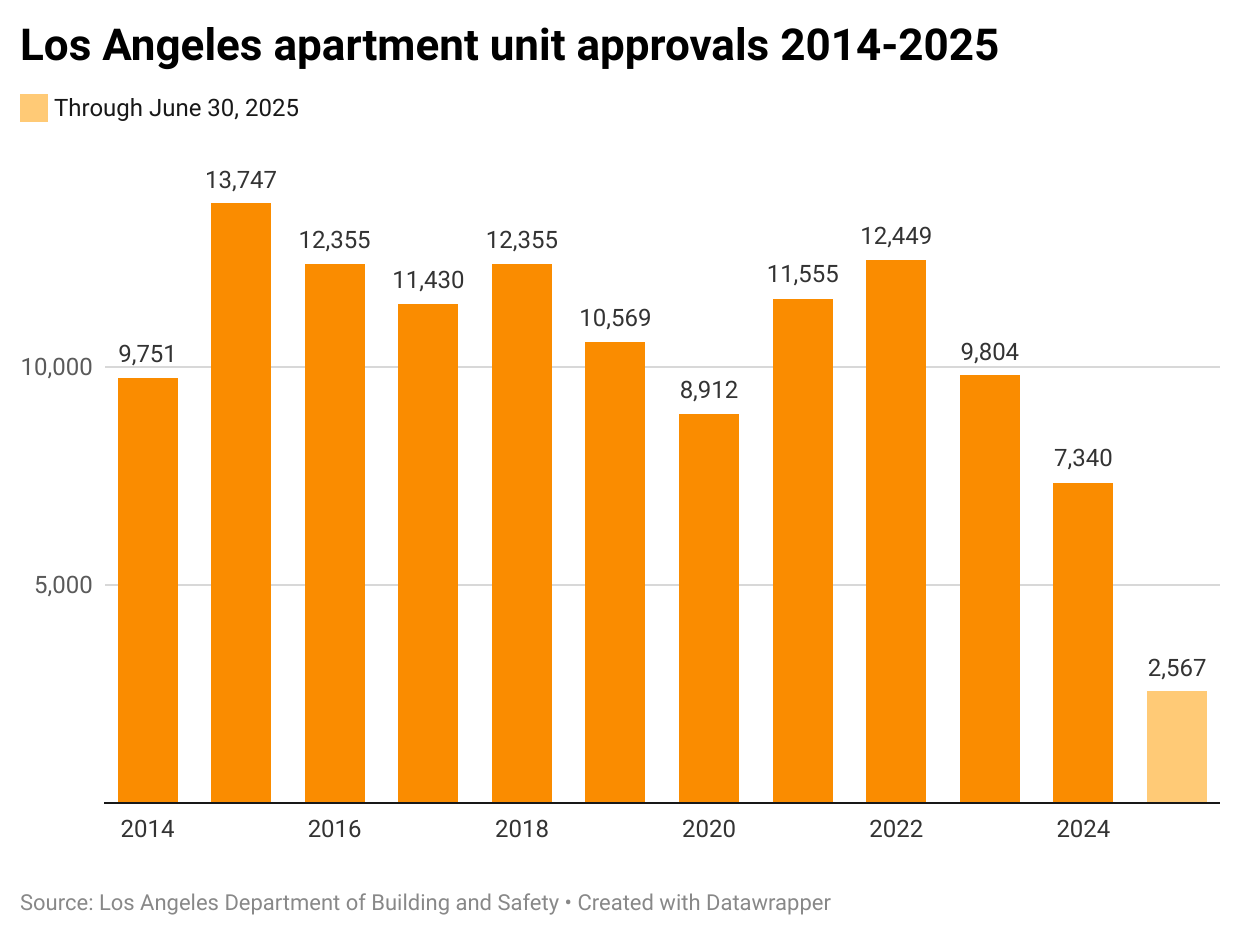

However, the biggest challenge remaining is the slow pace of building in the city. The number of new apartments being approved hit a decade low last year.

High costs, and other big challenges

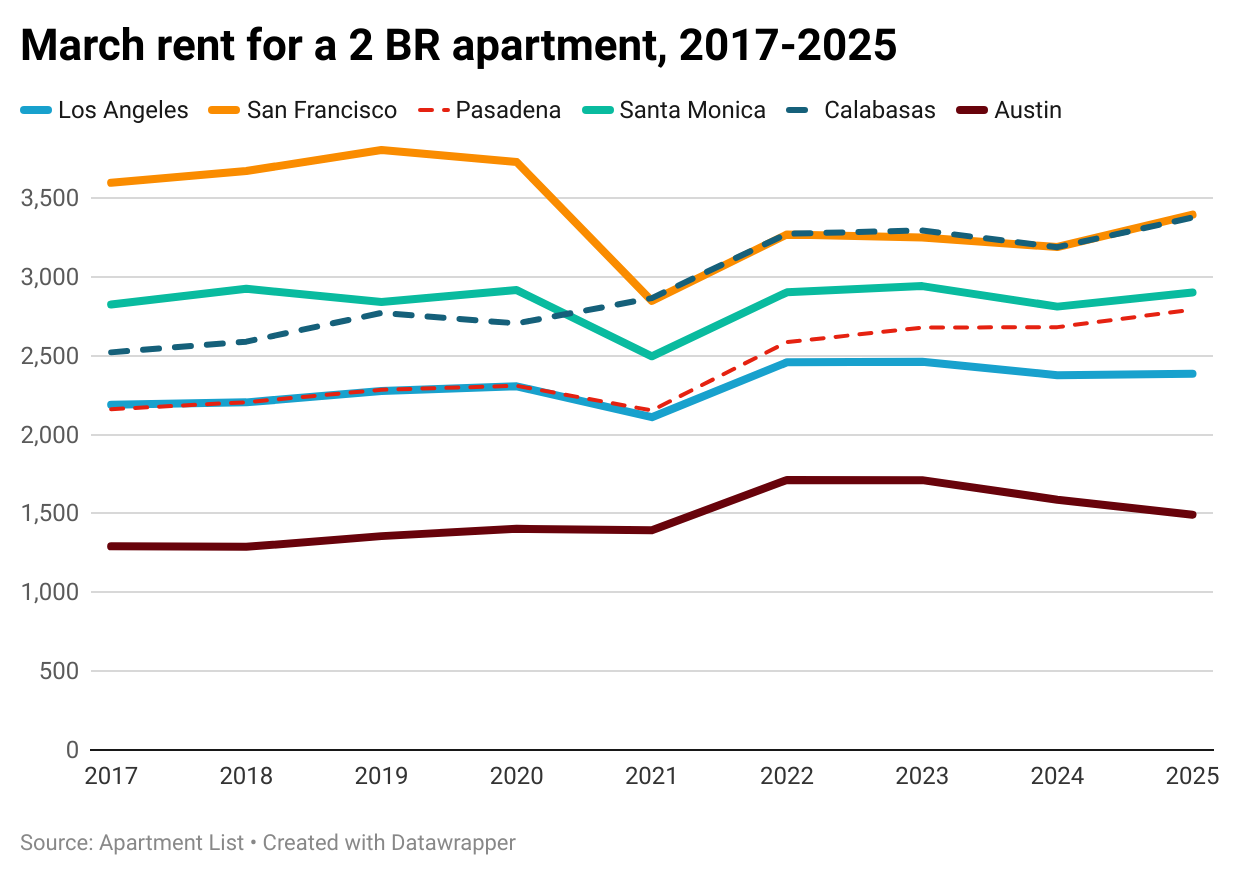

Other challenges to addressing homelessness include that Los Angeles remains a very expensive place to live. A two-bedroom apartment rents for an average of nearly $2,500 a month, according to data from ApartmentList.com.

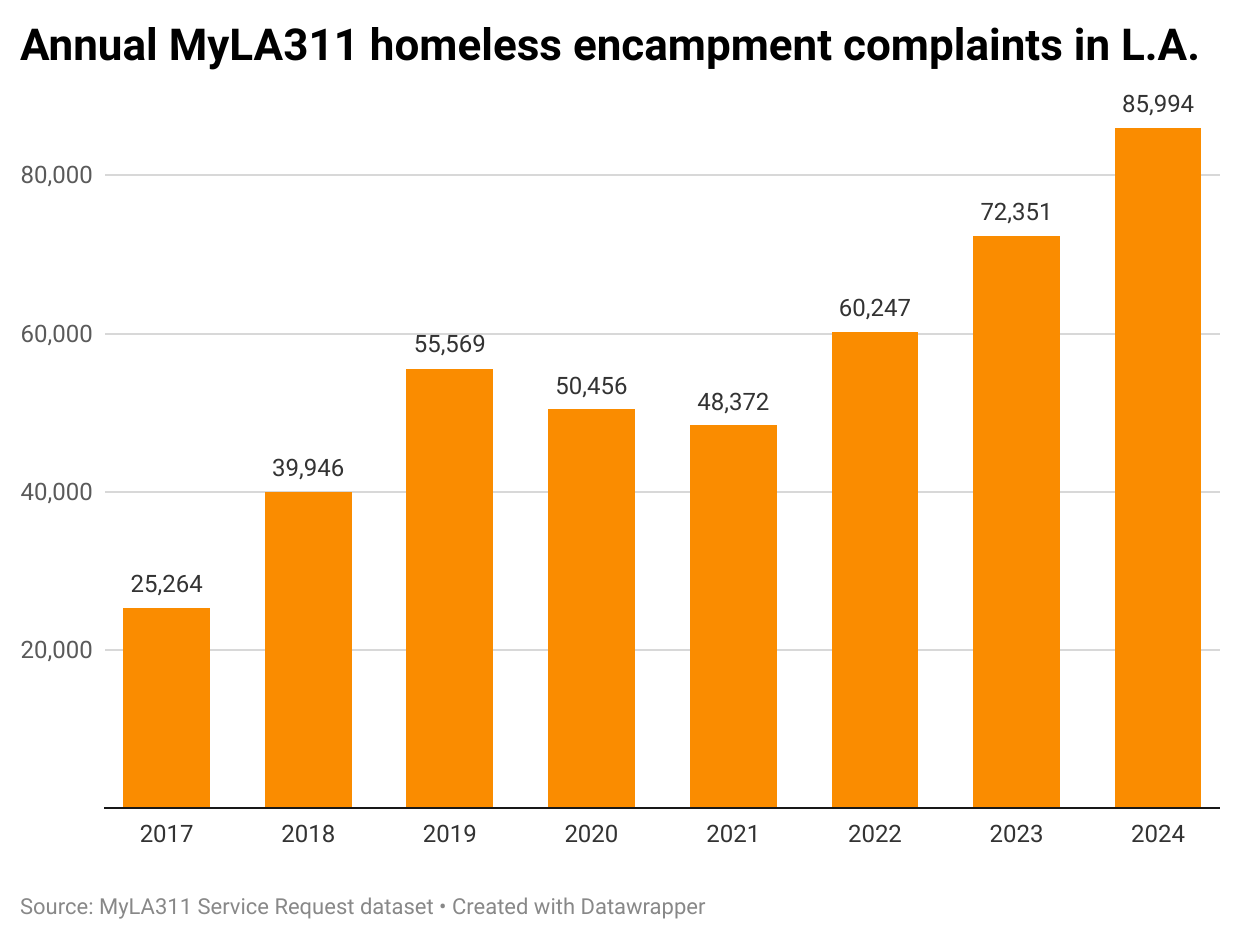

Another challenge is the dangers on the streets—each year approximately 2,000 people experiencing homelessness die in Los Angeles County, many due to overdoses. Then there is public sentiment; even with Inside Safe’s focus on encampments, there are clusters of tents across the city, sparking anger from some neighbors.

Further progress could be hampered by the city’s clash with the Trump administration over illegal immigration and ICE raids. Historically, federal funding is a key part of efforts to address homelessness.

There could also be an impact from a divide between city and county leaders. This spring, the County Board of Supervisors, over the objections of Bass, voted to pull hundreds of millions of dollars each year that it dedicates to LAHSA; this followed blistering audits about the organization’s tracking of spending.

The county is forming its own department to address homelessness. Some worry that this could result in less cooperation between the branches of government.

How we did it: We analyzed publicly available data from a variety of sources in the city of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count.